David Friedman addresses Pascal’s wager:

Pascal famously argued that, as long as there was any probability that God existed, a rational gambler should worship him, since the cost if he did exist and you failed to worship him was enormously greater than the cost if it went the other way around.

A variety of objections can be made to this, most obviously that a just God would reject a worshiper who worshiped on that basis.

That is my view, also. But Friedman goes on to say that he has “a variant on the argument” that he “find[s] more persuasive.” Thus:

The issue is not God but morality. Most human beings have a strong intuition that some acts are good and some bad–that one ought not to steal, murder, lie, bully, torture, and the like. Details of what is covered and how it is defined vary a good deal, but the underlying idea that right and wrong are real categories and one should do right and not wrong is common to most of us.

There are two categories of explanation for this intuition. One is that it is a perception–that right and wrong are real, that we somehow perceive that, and that our feel for what is right and what is wrong is at least very roughly correct. The other is that morality is a mistake. We have been brainwashed by our culture, or perhaps our genes, into feeling the way we do, but there is really no good reason why one ought to feed the hungry or ought not to torture small children.

Suppose you are uncertain which of the two explanations is correct. I argue that you ought to act as if the first is. If morality is real and you act as if it were not, you will do bad things–and the assumption that morality is real means that you ought not to do bad things. If morality is an illusion and you act as if it were not, you may miss the opportunity to commit a few pleasurable wrongs–but since morality correlates tolerably well, although not perfectly, with rational self interest, the cost is unlikely to be large.

I think this version avoids the problems with Pascal’s. No god is required for the argument–merely the nature of right and wrong, good and evil, as most human beings intuit them. And, by the morality most of us hold, the fact that you are refraining from evil because of a probabilistic calculation does not negate the value of doing so–you still haven’t stolen, lied, or whatever. One of the odd features of our intuitions of right and wrong is that they are not entirely, perhaps not chiefly, judgements about people but judgements about acts.

Friedman actually changes the subject from Pascal’s wager (why one should believe in God) to the basis of morality. As I say above, I agree with Friedman’s observation about Pascal’s wager: God might well reject a cynical believer.

But it seems to me that Pascal’s wager has nothing much to do with the origin of morality. Not all worshipers are moral; not all moral persons are worshipers.

Moreover, Friedman overlooks two important (and not mutually exclusive) explanations of morality. The first is empathy; the second is consequentialism.

We (most of us) flinch from doing things to others that we would not want done to ourselves. Is that because of inbred (“hard wired”) empathy? Or are we conditioned by social custom? Or is the answer “both”?

If inbred empathy is the only explanation for self-control with regard to other persons, why is it that our restraint so often fails us in interactions with others are fleeting and/or distant? (Think of aggressive driving and rude e-mails, for just two examples of unempathic behavior.) Empathy, to the extent that it is a real and restraining influence, seems most to work best (but not perfectly) in face-to-face encounters, especially where the persons involved have more than a fleeting relationship.

If behavior is (also) influenced by social custom, why does social custom favor restraint? Here is where consequentialism enters the picture.

We are taught (or we learn) about the possibility of retaliation by a victim of our behavior (or by someone acting on behalf of a victim). In certain instances, there is the possibility of state action on behalf of the victim: a fine, time in jail, etc. So we are taught (or we learn) to restrain ourselves (to some extent) in order to avoid punishments that flow directly and (more or less) predictably from our unrestrained actions.

More deeply, there is the idea that “what goes around comes around.” In other words, bad behavior can beget bad behavior, whereas good behavior can beget good behavior. (“Well, if so-and-so can get away with X, so can I.” “So-and-so is rewarded for good behavior; it will pay me to be good, also.” “If so-and-so is nice to me, I’ll be nice to him so that he’ll continue to be nice to me.”)

Why do we care that “what goes around comes around”? First, we humans are imitative social animals; what others do — for good or ill — cues our own behavior. Second, there is an “instinctive” (taught/learned) aversion to “fouling one’s own nest.”

Unfortunately, our aversion to nest-fouling weakens as our interactions with others become more fleeting and distant — as they have done since the onset of industrialization, urbanization, and mass communication. Bad behavior then becomes easier because its consequences are less obvious or certain; it becomes a model for imitation and, perhaps, even a norm. Good behavior then flows from the fear of being retaliated against, not from socialized norms, or even from fear of state action. Aggression — among the naturally aggressive — becomes more usual.

And so we become ripe for rule by a “protective” state, and by rival warlords if the state fails to protect us.

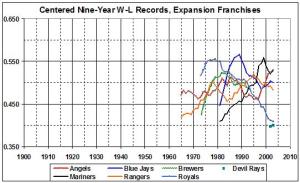

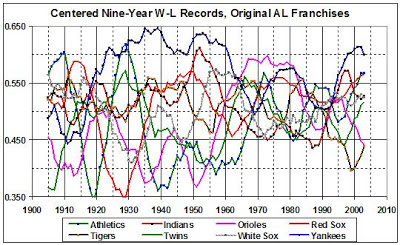

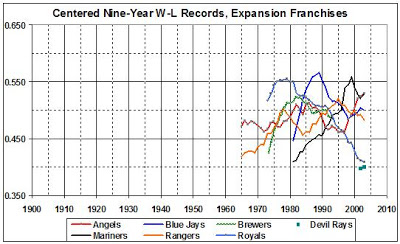

Remember, I am measuring performance over nine-year spans — not individual seasons — so the following lists will not always correspond with lists of teams having the best and worst W-L record, by season. Using the nine-year, I present the best (E = expansion team)…

Remember, I am measuring performance over nine-year spans — not individual seasons — so the following lists will not always correspond with lists of teams having the best and worst W-L record, by season. Using the nine-year, I present the best (E = expansion team)…