Can the economic cost of government be estimated? I have done it for the post-World War II era, in an analysis that takes account of the fraction of GDP absorbed by federal, State, and local governments; the rate at which the federal government issues new regulations; the constant-dollar value of business investment (which is influenced by government spending and regulation); and changes in the consumer price index.

But that analysis doesn’t tell the whole story. In fact, it leaves untold the big story: The United States has been in a mega-depression since 1907.

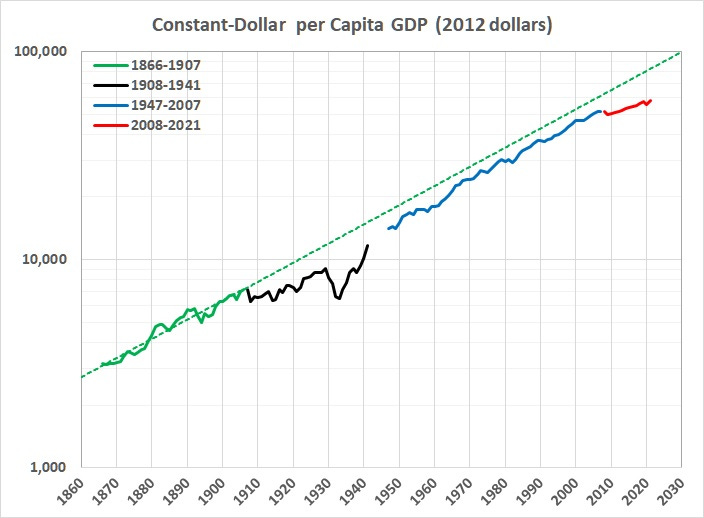

Consider the following graph, which is derived from estimates of constant-dollar GDP per capita that are available here:

There are four eras, as shown by the legend (1942-1946 omitted because of the vast economic distortions caused by World War II):

- 1866-1907 — annual growth of 2.0 percent — A robust economy, fueled by (mostly) laissez-faire policies and the concomitant rise of industry, mass production, technological innovation, and entrepreneurship.

- 1908-1941 — annual growth of 1.4 percent — A dispirited economy, shackled by the fruits of “progressivism”; for example, trust-busting; the onset of governance through regulation; the establishment of the income tax; the creation of the destabilizing Federal Reserve; and the New Deal, which prolonged the Great Depression.

- 1947- 2007 — annual growth of 2.2 percent — A rejuvenated economy, buoyed by the end of the New Deal and the fruits of advances in technology and business management. The rebound in the rate of growth meant that the earlier decline wasn’t the result of an “aging” economy, which is an inapt metaphor for a living thing that is constantly replenished with new people, new capital, and new ideas.

- 2008-2021 — annual growth of 1.0 percent — An economy sagging under the cumulative weight of the fruits of “progressivism” (old and new); for example, the never-ending expansion of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security; and an ever-growing mountain of regulatory restrictions on business. (In a similar post, which I published in 2009, I wrote presciently that “[u]nless Obama’s megalomaniacal plans are aborted by a reversal of the Republican Party’s fortunes, the U.S. will enter a new phase of economic growth — something close to stagnation.)

Had the economy of the U.S. not been deflected from the course that it was on from 1866 to 1907, per capita GDP would now be about 1.4 times its present level. Compare the position of the dashed green line in 2021 — $83,000 — with per capita GDP in that year — $58,000.

If that seems unbelievable to you, it shouldn’t. A growing economy is a kind of compound-interest machine; some of its output is invested in intellectual and physical capital that enables the same number of workers to produce more, better, and more varied products and services. (More workers, of course, will produce even more products and services.) As the experience of 1947-2007 attests, nothing other than government interventions (or a war far more devastating to the U.S than World War II) could have kept the economy from growing along the path of 1866-1907. (I should add that economic growth in 1947-2007 would have been even greater than it was but for the ever-rising tide of government interventions.)

The sum of the annual gaps between what could have been (the dashed green line) and the reality after 1907 (omitting 1942-1946) is almost $700,000 — that’s per person in 2012 dollars. It’s $800,000 per person in 2021 dollars, and even more in 2022 dollars.

That cumulative gap represents our mega-depression.

The mega-depression is an example of “that which is not seen”, a coinage of Frédéric Bastiat. In “That Which Is Seen and That Which Is Not Seen”, Bastiat writes:

Have you ever chanced to hear it said “There is no better investment than taxes. Only see what a number of families it maintains, and consider how it reacts on industry; it is an inexhaustible stream, it is life itself.” . . .

The advantages which officials advocate are those which are seen. The benefit which accrues to the providers is still that which is seen. This blinds all eyes.

But the disadvantages which the tax-payers have to get rid of are those which are not seen. And the injury which results from it to the providers, is still that which is not seen, although this ought to be self-evident.

When an official spends for his own profit an extra hundred sous, it implies that a tax-payer spends for his profit a hundred sous less. But the expense of the official is seen, because the act is performed, while that of the tax-payer is not seen, because, alas! he is prevented from performing it.

In the case of aggregate economic activity, what we see is what has been left to us by government. What we do not see is the extent to which the fruits of labor taken from us by government and the restrictions placed upon economic activity by government have deprived the economy of entrepreneurship, innovation, technology, and productive capacity. The cumulative effect of those deprivations — that which we do not see — dwarfs the Great Depression.