The so-called 97-percent consensus among climate scientists about anthropogenic global warming (AGW) isn’t evidence of anything but the fact that scientists are only human. Even if there were such a consensus, it certainly wouldn’t prove the inchoate theory of AGW, any more than the early consensus against Einstein’s special theory of relativity disproved that theory.

Actually, in the case of AGW, the so-called consensus is far from a consensus about the extent of warming, its causes, and its implications. (See, for example, this post and this one.) But it’s undeniable that a lot of climate scientists believe in a “strong” version of AGW, and in its supposedly dire consequences for humanity.

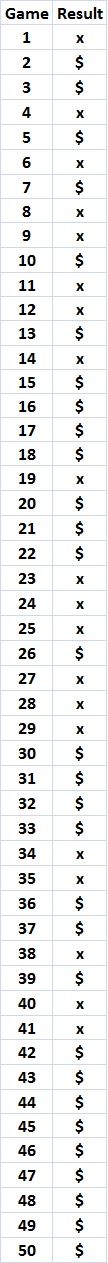

Why is that? Well, in a field as inchoate as climate science, it’s easy to let one’s prejudices drive one’s research agenda and findings, even if only subconsciously. And isn’t it more comfortable and financially rewarding to be with the crowd and where the money is than to stand athwart the conventional wisdom? (Lennart Bengtsson certainly found that to be the case.) Moreover, there was, in the temperature records of the late 20th century, a circumstantial case for AGW, which led to the development of theories and models that purport to describe a strong relationship between temperature and CO2. That the theories and models are deeply flawed and lacking in predictive value seems not to matter to the 97 percent (or whatever the number is).

In other words, a lot of climate scientists have abandoned the scientific method, which demands skepticism, in order to be on the “winning” side of the AGW issue. How did it come to be thought of as the “winning” side? Credit vocal so-called scientists who were and are (at least) guilty of making up models to fit their preconceptions, and ignoring evidence that human-generated CO2 is a minor determinant of atmospheric temperature. Credit influential non-scientists (e.g., Al Gore) and various branches of the federal government that have spread the gospel of AGW and bestowed grants on those who can furnish evidence of it. Above all, credit the media, which for the past two decades has pumped out volumes of biased, half-baked stories about AGW, in the service of the “liberal” agenda: greater control of the lives and livelihoods of Americans.

Does this mean that the scientists who are on the AGW bandwagon don’t believe in the correctness of AGW theory? I’m sure that most of them do believe in it — to some degree. They believe it at least to the same extent as a religious convert who zealously proclaims his new religion to prove (mainly to himself) his deep commitment to that religion.

What does all of this have to do with the Monty Hall problem? This:

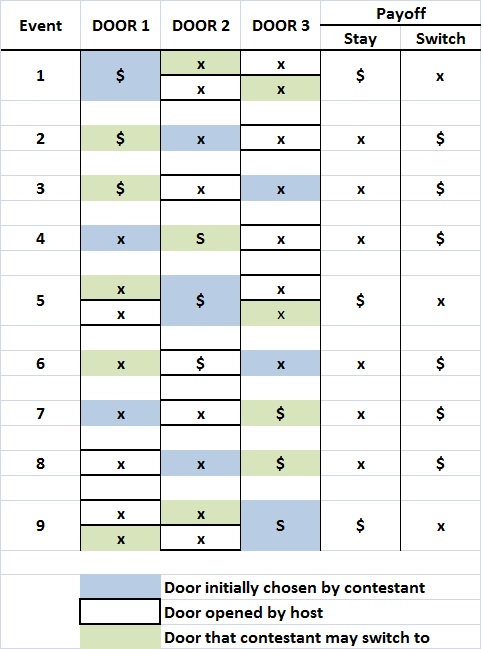

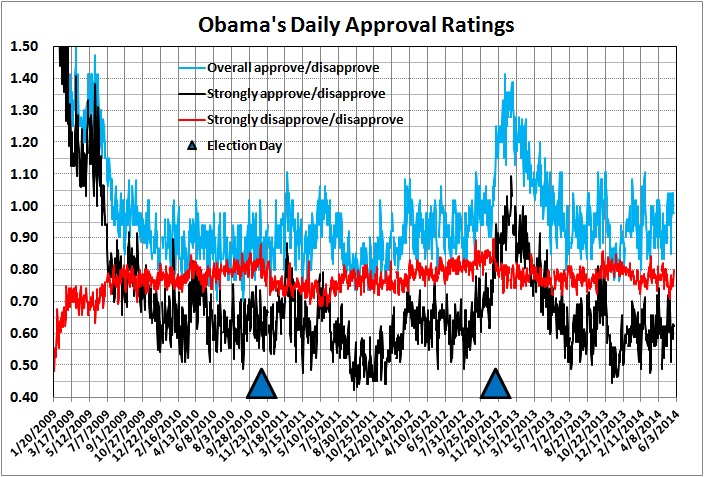

Making progress in the sciences requires that we reach agreement about answers to questions, and then move on. Endless debate (think of global warming) is fruitless debate. In the Monty Hall case, this social process has actually worked quite well. A consensus has indeed been reached; the mathematical community at large has made up its mind and considers the matter settled. But consensus is not the same as unanimity, and dissenters should not be stifled. The fact is, when it comes to matters like Monty Hall, I’m not sufficiently skeptical. I know what answer I’m supposed to get, and I allow that to bias my thinking. It should be welcome news that a few others are willing to think for themselves and challenge the received doctrine. Even though they’re wrong. (Brian Hayes, “Monty Hall Redux” (a book review), American Scientist, September-October 2008)

The admirable part of Hayes’s statement is its candor: Hayes admits that he may have adopted the “consensus” answer because he wants to go with the crowd.

The dismaying part of Hayes’s statement is his smug admonition to accept “consensus” and move on. As it turns out the “consensus” about the Monty Hall problem isn’t what it’s cracked up to be. A lot of very bright people have solved a tricky probability puzzle, but not the Monty Hall problem. (For the details, see my post, “The Compleat Monty Hall Problem.”)

And the “consensus” about AGW is very far from being the last word, despite the claims of true believers. (See, for example, the relatively short list of recent articles, posts, and presentations given at the end of this post.)

Going with the crowd isn’t the way to do science. It’s certainly not the way to ascertain the contribution of human-generated CO2 to atmospheric warming, or to determine whether the effects of any such warming are dire or beneficial. And it’s most certainly not the way to decide whether AGW theory implies the adoption of policies that would stifle economic growth and hamper the economic betterment of millions of Americans and billions of other human beings — most of whom would love to live as well as the poorest of Americans.

Given the dismal track record of global climate models, with their evident overstatement of the effects of CO2 on temperatures, there should be a lot of doubt as to the causes of rising temperatures in the last quarter of the 20th century, and as to the implications for government action. And even if it could be shown conclusively that human activity will temperatures to resume the rising trend of the late 1900s, several important questions remain:

- To what extent would the temperature rise be harmful and to what extent would it be beneficial?

- To what extent would mitigation of the harmful effects negate the beneficial effects?

- What would be the costs of mitigation, and who would bear those costs, both directly and indirectly (e.g., the effects of slower economic growth on the poorer citizens of thw world)?

- If warming does resume gradually, as before, why should government dictate precipitous actions — and perhaps technologically dubious and economically damaging actions — instead of letting households and businesses adapt over time by taking advantage of new technologies that are unavailable today?

Those are not issues to be decided by scientists, politicians, and media outlets that have jumped on the AGW bandwagon because it represents a “consensus.” Those are issues to be decided by free, self-reliant, responsible persons acting cooperatively for their mutual benefit through the mechanism of free markets.

* * *

Recent Related Reading:

Roy Spencer, “95% of Climate Models Agree: The Observations Must Be Wrong,” Roy Spencer, Ph.D., February 7, 2014

Roy Spencer, “Top Ten Good Skeptical Arguments,” Roy Spencer, Ph.D., May 1, 2014

Ross McKittrick, “The ‘Pause’ in Global Warming: Climate Policy Implications,” presentation to the Friends of Science, May 13, 2014 (video here)

Patrick Brennan, “Abuse from Climate Scientists Forces One of Their Own to Resign from Skeptic Group after Week: ‘Reminds Me of McCarthy’,” National Review Online, May 14, 2014

Anthony Watts, “In Climate Science, the More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same,” Watts Up With That?, May 17, 2014

Christopher Monckton of Brenchley, “Pseudoscientists’ Eight Climate Claims Debunked,” Watts Up With That?, May 17, 2014

John Hinderaker, “Why Global Warming Alarmism Isn’t Science,” PowerLine, May 17, 2014

Tom Sheahan, “The Specialized Meaning of Words in the “Antarctic Ice Shelf Collapse’ and Other Climate Alarm Stories,” Watts Up With That?, May 21, 2014

Anthony Watts, “Unsettled Science: New Study Challenges the Consensus on CO2 Regulation — Modeled CO2 Projections Exaggerated,” Watts Up With That?, May 22, 2014

Daniel B. Botkin, “Written Testimony to the House Subcommittee on Science, Space, and Technology,” May 29, 2014

Related posts:

The Limits of Science

The Thing about Science

Debunking “Scientific Objectivity”

Modeling Is Not Science

The Left and Its Delusions

Demystifying Science

AGW: The Death Knell

Modern Liberalism as Wishful Thinking

The Limits of Science (II)

The Pretence of Knowledge

“The Science Is Settled”