The subject of updating libertarianism was introduced by Randy Barnett at Law & Liberty (“Libertarianism Updated“). Barnett’s piece was followed by Ilya Somin’s alternative view at The Dispatch (“Libertarianism Needs Careful Tweaks, Not Wholesale Updates“). Then came Timothy Sandefur’s piece, “Libertarianism Doesn’t Need an Update“, which is adamantly against updates (and possibly against tweaks).

I won’t try to reconcile the three writers’ views or explain how they differ. I will focus on a particular aspect of Sandefur’s offering. Among his various defenses of libertarianism as it is, he says this:

[L]bertarianism is skeptical, even pessimistic, about human capacities—especially those of the humans who wield government power, and are as fallible as the rest of us, if not more so. Precisely because libertarianism does not make idealized assumptions about people’s behavior—and holds that utopia is impossible—it concludes that the least bad alternative is to leave people free to make their own choices (subject to legal accountability if they harm others). After all, they have a stronger incentive to avoid bad decisions in their own lives than any outsider could possibly have.

Before I “unpack” this paragraph, I should note that Sandefur’s article doesn’t offer a way to attain a libertarian (or more-libertarian) polity. Not that it matters; the prospect of a polity in which citizens were left to make their own choices is probably frightening to most people. I suspect that such a polity is mainly attractive to intelligent, articulate, self-confident, introverts who are like-minded (or believe themselves to be like-minded) about the rules of the game — you will be left alone as long as you don’t do harm to me — and (most important) about what constitutes harm. Whether they would be self-reliant enough to thrive in such a regime is another matter.

(“Leave me alone” libertarianism was closest to attainment in days long gone by when Americans thought more or less alike about morality and punishments for transgressions of it, and when governments in the United States had yet to regulate the minutiae of economic and social intercourse. Now, libertarianism is a mainly a watchword for the types described above and petulant “rebels” against rules that inconvenience them, such as retirement-community rules about keeping one’s garage door closed and promptly retrieving one’s emptied trash bin from the curb.)

The passage before the preceding parenthetical leads to the question of what happens if a harm is committed. Thus enters the absurd notion private-enforcement agencies (a.k.a. competing gangs) or the more appealing notion of the night-watchman state. The latter isn’t strictly libertarian (as a anarcho-capitalist purist would define it) but is considered by many to be the direction in which libertarianism points, in the context of the typical Western polity: a deeply ingrained regulatory-welfare state with a constituency that comprises most of the populace.

The night-watchman state would enforce the rules against harm, assuming — ridiculously at this point in America’s social history — that America’s “leaders” acquiesce to the wishes of an unshakeable majority of the populace regarding the list of harms. And the night-watchman state and would enforce those rules both within the polity and against outside entities who inflict harm — or are undoubtedly preparing to inflict harm — upon members of the polity’s populace. (NB: The preemptive actions implied in the preceding sentence would also require the support of an unshakeable majority of Americans and the acquiescence of “leaders” to that majority.)

Now, let’s consider the previously quoted paragraph from Sandefur’s article as a justification for making a transition from a regulatory-welfare state to a night-watchman state, beginning with this:

[L]bertarianism is skeptical, even pessimistic, about human capacities—especially those of the humans who wield government power, and are as fallible as the rest of us, if not more so.

I am skeptical of the capacities (and true intentions) of most human beings, in that they are (saints excepted) mostly convinced that things should be organized to suit their individual preferences. Not the least of those preferences is the urge to acquire greater income and wealth with little or no effort.

It follows that, all protestations to the contrary notwithstanding, most human beings will seek to empower politicians who promise to arrange things in preferred ways and to enrich preferred persons (without acknowledging, of course, that the cost of said enrichment will be borne by non-preferred persons). Those politicians, in turn, will erect bureaucracies devoted to the aforementioned ends — bureaucracies that will continue to churn out edicts that foster the same ends almost regardless of which set of politicians is currently in power. The bureaucrats thereby satisfy their power lusts, and the politicians do the same, as well as gaining opportunities for personal enrichment without (necessarily) committing patently criminal acts.

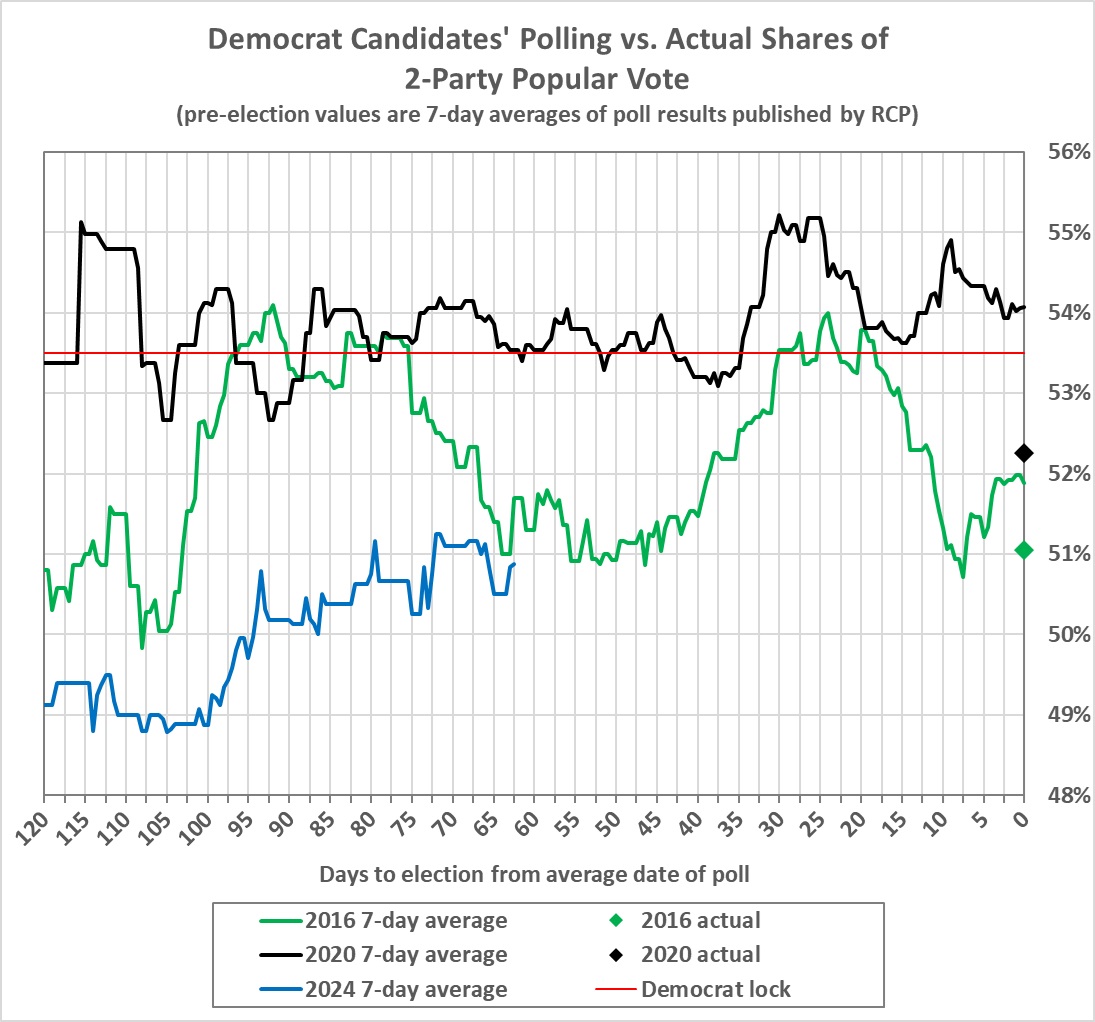

Given that political contests in the United States usually involve a choice between two candidates with the same motivations toward power (if not enrichment), choosing the least bad alternative becomes a matter of voters’ preferences regarding the policies that competing candidates espouse or represent. And, except in the case of the presidency of the United States, the winner is the candidate who gets the most votes, usually by a combination of voters’ ignorance and inertia couple with the promise of delivering policies favored by a majority. Those policies will include ways to empower and enrich various segments of the populace (at the expense of other segments). Thus the course of American politics and governance has been toward the engrossment of government, its share of the economy, and its command of economic and social transactions from the founding of the Republic. You can look it up.

So much for that. Now for the second sentence of the quoted paragraph:

Precisely because libertarianism does not make idealized assumptions about people’s behavior—and holds that utopia is impossible—it concludes that the least bad alternative is to leave people free to make their own choices (subject to legal accountability if they harm others).

Because true libertarians (as opposed to faux rebels) are as scarce as hens’ teeth (for the reasons adduced above), the least bad alternative lacks enough allure to fuel an electoral revolution. Witness the general state of fear and loathing that accompanies the merest possibility that the federal government might shut down, or the actuality that it does shut down (albeit with many loopholes) for even a few days.

Which brings us to the final sentence of the quoted paragraph:

After all, [people] have a stronger incentive to avoid bad decisions in their own lives than any outsider could possibly have.

Those candidates who campaign on a platform of reducing the size, power, and cost of government are at a great disadvantage because most Americans — as citizens of the United States, the several States, and myriad political subdivisions of the States — are wedded to and dependent upon government-bestowed (and tax- or debt-funded) benefits that they would be loath to forgo. What most of them want is to eat their cake (enjoy government-bestowed benefits) and have it too (reduce the size, power, and cost of government).

In that respect, Republicans have proven to be Democrats who wait a while before accepting the enlargements of government power, size, and cost introduced (usually) by Democrats. (It’s worth noting here that the Nixon-Ford administrations ramped up regulation to a new level; the Reagan-G.W. Bush administrations did nothing to change that and Bush added the Americans with Disabilities Act, which among many things, has resulted in a plethora of unused parking spaces across the land; G.W. Bush contributed Medicare coverage of drug costs, just in time for retiring Boomers and those who will follow them.)

If Trump is reelected that best that can be hoped for is a slowing of the growth in the number of federal regulations and perhaps a return to energy self-sufficiency. That’s not chopped liver; Americans will be better off than they would be under a Harris regimes. But the abolition of one or more cabinet departments and “independent” agencies is a pipe dream. Perhaps the “deep state” will be weeded out, but weeds are notoriously prone to come back, as they will under the next Democrat administration, unless there’s a great awakening. Don’t count on it.

“Pipe dream” is best thing I can say about libertarianism. Although theorizing about it seems to be an enjoyable pastime for a goodly number of “public intellectuals”. I would say that it keeps them off the streets but effeteness isn’t a scary trait.