In “Testing for Steroids” I examine the records of the eleven most prolific home-run hitters in the history of major-league baseball: Mark McGwire, Barry Bonds, and nine other. The graphs I present in “Testing…” show that the late-career accomplishments of McGwire and Bonds are far out of line with (a) their earlier accomplishments and (b) the career patterns of the other nine sluggers. In sum, there is a strong statistical case for the proposition that McGwire and Bonds used and benefited from performance-enhancing drugs.

Is there similar evidence (pro or con) regarding Roger Clemens? There’s an analysis released by Clemens’s agents (the “Clemens Report“), which is (rightly) found wanting by Justin Wolfers (writing at the Freakonomics blog, here and here). I am not, however, smitten with Wolfers’s rather vague statistical presentation. Steven Levitt (also writing at the Freakonomics blog) points to a better one, by Nate Silver.

I had been working on my own analysis before I came upon Silver’s. Though our approaches are somewhat different, Silver and I reach the same conclusion: “where [Clemens’s] statistical record is concerned, there is no smoking gun.” Or, as Levitt says,

While statistical evidence can sometimes provide convincing evidence that something really out of the ordinary has happened (like the sumo wrestling cheating that was documented in Freakonomics), it is far from clear how to interpret the findings when things look normal.

The statistical case against McGwire and Bonds is compelling. There is no statistical case against Clemens. He may have used steroids and HGH, as alleged by Brian McNamee, but the numbers don’t prove it.

For my analysis, I draw on Baseball-Reference.com to compare Clemens’s record with the records of pitchers who are his peers:

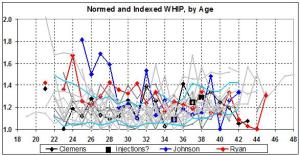

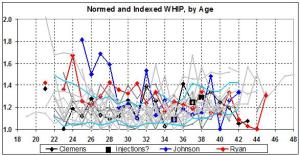

- First, I compare Clemens with other highly successful and durable pitchers on the basis of walks-plus-innings pitched (WHIP), by age. I define highly successful pitchers as those who have won at least 250 games in the “live-ball era.” Durable pitchers, for the purpose of this comparison, also pitched at least 100 innings in at least one season at the age of 40 (or older).

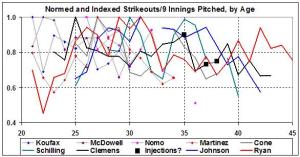

- Second, I compare Clemens with other starting pitchers who averaged more than 8 strikeouts per 9 innings pitched (SO/9IP) during their careers, and who also pitched at least 100 innings in each of 10 or more seasons.

For the pitchers who meet those criteria, I omit intra-career seasons of less than 100 innings. Further, I adjust each season’s statistics by

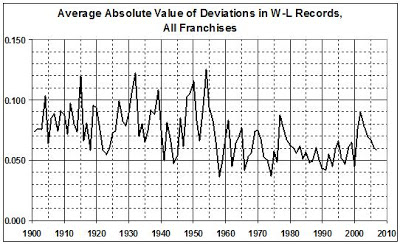

- normalizing for differences between leagues and across time (which are substantial*), and

- indexing each pitcher’s statistics to the pitcher’s best season, in order to compare relative changes in the performance of pitcher A during his career with relative changes in the performance of pitchers B, C, etc., during their careers.

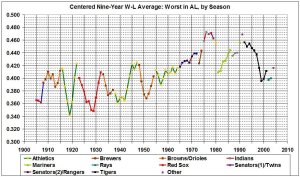

The 18 highly successful, durable pitchers included in my analysis are (in order of first 100-inning season): Ted Lyons (1924, 260 career wins), Lefty Grove (1925, 300), Early Wynn (1942, 300), Warren Spahn (1946, 363), Jim Kaat (1961, 283), Tommy John (1965, 288), Ferguson Jenkins (1966, 284), Gaylord Perry (1964, 314), Don Sutton (1966, 324), Steve Carlton (1967, 329), Phil Niekro (1967, 318), Tom Seaver (1967, 311), Nolan Ryan (1968, 324), Bert Blyleven (1970, 287), Roger Clemens (1984, 354), Greg Maddux (1987, 347), Tom Glavine (1988, 303), and Randy Johnson (1989, 284).

To keep the following graph simple, I highlight only the careers of Ryan, Johnson, and Clemens (indicating the seasons in which he is alleged to have received injections of steroids and/or HGH). (For a better view of the graphs in this post, right-click on them and select “open in new tab.”) The gray lines represent the careers of the other 15 pitchers. The light blue lines indicate the normal range of those 15 pitchers’ career trajectories. (The normal range is the range that contains about two-thirds of each year’s observations; about one-third of them are on either side of each year’s mean.) The shape of the light blue lines tells the expected tale: improvement, a peak (around age 30-32), and deterioration.

The career patterns of Clemens, Johnson, and Ryan are atypical. But they are atypical in different ways. Clemens’s record is up and down. His improvement in the late years is striking, but no more striking than that of Ryan, who simply follows a different trajectory (steady improvement) to arrive at about the same place at about the same age. Johnson’s trajectory is similar to Ryan’s, but with more ups and downs. Like Ryan, Johnson peaks very late. Johnson’s sudden deterioration following his peak can be attributed to his well-known back problems; Ryan’s, to sheer age.

The career patterns of Clemens, Johnson, and Ryan are atypical. But they are atypical in different ways. Clemens’s record is up and down. His improvement in the late years is striking, but no more striking than that of Ryan, who simply follows a different trajectory (steady improvement) to arrive at about the same place at about the same age. Johnson’s trajectory is similar to Ryan’s, but with more ups and downs. Like Ryan, Johnson peaks very late. Johnson’s sudden deterioration following his peak can be attributed to his well-known back problems; Ryan’s, to sheer age.

In sum, Clemens had a more consistent career than those of Johnson and Ryan. But Clemens’s late-career success cannot be deemed suspicious when viewed against the similar successes of Johnson and Ryan.

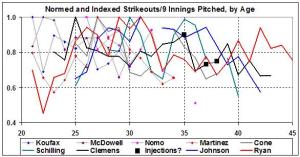

Turning to the the leading “power pitchers,” we have Sandy Koufax (first 100-inning year, 1957; 9.28 SO/9IP for his career), Sam McDowell (1964, 8.86), Nolan Ryan (1968, 9.55), Roger Clemens (1984, 8.55), David Cone (1988, 8.28), Randy Johnson (1989, 10.78), Curt Schilling (1992, 8.60), Pedro Martinez (1993, 10.20), and Hideo Nomo (1995, 8.74):

Only four of the nine pitched 100 innings in a season at age 40 (or older): Schilling, Clemens, Johnson, and Ryan. Among that select group, Clemens’s record is unexceptional. His late surge (local peaks at ages 35 and 39) is no more extreme than the late surges of Schilling (at 35), Johnson (at 37), and Ryan (at 40 and 42).

Only four of the nine pitched 100 innings in a season at age 40 (or older): Schilling, Clemens, Johnson, and Ryan. Among that select group, Clemens’s record is unexceptional. His late surge (local peaks at ages 35 and 39) is no more extreme than the late surges of Schilling (at 35), Johnson (at 37), and Ryan (at 40 and 42).

There is no statistical case against Roger Clemens. Did he “do it”? Maybe. But the proof of “it” requires hard, physical evidence (or an admission by Clemens), not statistical analysis.

The inconclusiveness of of statistical analysis, in this case, may mean one of two things: (1) Clemens didn’t use performance-enhancing drugs. (2) If Clemens relied mainly on HGH (as opposed to steroids) in an effort to bolster his performance, the effect may have been nil. For example,

there is no proof that net protein retention is promoted in adults, except possibly of connective tissue. The overexaggeration of the effects of growth hormone in muscle building is effectively promoting its abuse and thereby encouraging athletes and elderly men to expose themselves to increased risk of disease for little benefit.

Clemens may simply be living proof of the benefits of physical fitness.

__________

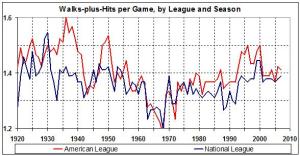

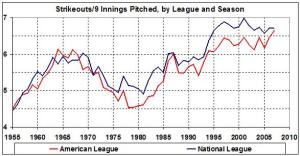

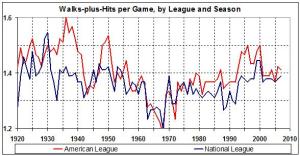

* WHIP and SO/9IP vary considerably by league and across time, for many reasons: expansion, the introduction of the designated hitter to the American League (1974), the replacement of old ball parks with new (sometimes smaller) ones, and variations in such things as the strike zone, the height of the pitching mound, the size of fielders’ gloves, the resiliency of the baseball, and the frequency with which umpires put a new ball into play.

To illustrate changes in WHIP, I use a closely related number: walks-plus-hits per game. Here’s the tally, by league and season for 1920-2007 (a period that spans the careers of the durable, highly successful pitchers whose records I analyze in this post):

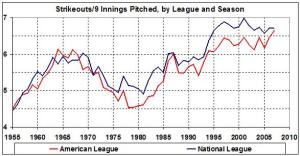

And here’s the tally of SO/9IP, by league and season for 1955-2007 (a period that covers the careers of the top “power pitchers” whose records I analyze in this post):

And here’s the tally of SO/9IP, by league and season for 1955-2007 (a period that covers the careers of the top “power pitchers” whose records I analyze in this post):