The American League had eight teams from 1901 through 1960; the National League had eight teams from 1901 through 1961. I have written elsewhere about post-1960/61 expansion and its influence on the quality and competitiveness of baseball. I focus here on three of the AL’s original franchises: the three with the worst overall records, among the original eight, from 1901 through 2007.

The three franchises — now known as the Oakland Athletics, Minnesota Twins, and Baltimore Orioles — are noteworthy not just because they, among the original eight, have won the lowest proportion of regular-season games. They are noteworthy also because they were the among the six major league teams to pick up and move in the span 1953-61. (The three NL teams that moved were the Braves, from Boston to Milwaukee in 1953 — and thence to Atlanta in 1966; the Dodgers, from Brooklyn to Los Angeles in 1958; and the Giants, from New York to San Francisco in 1958)

Going back a bit, the American League’s eight original franchises had stayed put from 1903 through 1953. The Baltimore Orioles franchise (1901-2) became the New York Highlanders in 1903 (renamed the Yankees in 1913). The Milwaukee Brewers franchise (1901) resided in St. Louis (as the Browns) from 1902 through 1953. The Browns, in 1954, became — and remain — the Baltimore Orioles.

One year after the Browns’ shift to Baltimore, the Philadelphia Athletics jumped to Kansas City, where they played 1955-67. The A’s then packed off to Oakland where they have been from 1968 to the present.

Then came the metamorphosis of the Washington Senators, often last in the American League during the years 1901-60. The Nats (a nickname of yore) were reborn in 1961 as the still-extant Minnesota Twins.

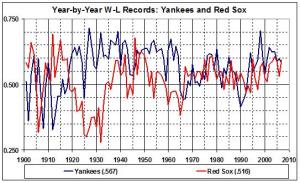

Why did the Browns, A’s, and Senators move? Short answer: Fans don’t flock to see losers. And losers they had been, and often continued to be. Here are their season-by-season records for 1901 through 2007 (overall records shown in the legend):

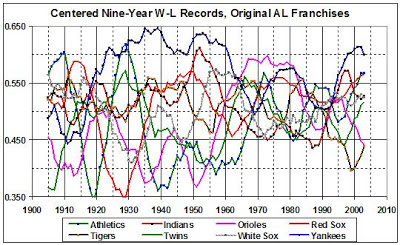

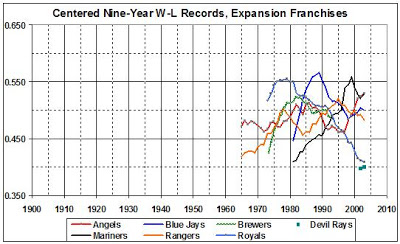

And here are easier-to-read (and more informative) nine-year records:

And here are easier-to-read (and more informative) nine-year records:

Fans of the reborn Browns (Orioles) and Senators (Twins) didn’t suffer long before the replanted franchises produced winners. The Orioles got a fresh start under new ownership, following Bill Veeck‘s disastrous years at the Browns’ helm. The Senators/Twins remained under Calvin Griffith‘s control for more than two decades, however. So, it would seem that a change of scenery (more tickets sold to newly enchanted fans) can go just as far as a change of ownership (more money to spend on players’ salaries).

Fans of the reborn Browns (Orioles) and Senators (Twins) didn’t suffer long before the replanted franchises produced winners. The Orioles got a fresh start under new ownership, following Bill Veeck‘s disastrous years at the Browns’ helm. The Senators/Twins remained under Calvin Griffith‘s control for more than two decades, however. So, it would seem that a change of scenery (more tickets sold to newly enchanted fans) can go just as far as a change of ownership (more money to spend on players’ salaries).

What about the A’s? They moved to Kansas City under new ownership, after more than five decades under Connie Mack and his sons. But that didn’t pan out; the A’s remained a lousy team. Another new owner (Charles O. Finley) moved the team from Kansas City to Oakland. A few years passed and the A’s became big winners, for a while. In this instance, success followed both a change of scenery and new ownership.

New ownership can work against a team, of course. It has in the case of the O’s, whose resurgence in the 1990s was reversed by an especially obnoxious and meddlesome owner, Peter Angelos. In that vein, it is obvious that the New York Yankees‘ resurgence in the mid-to-late 1970s is owed to George Steinbrenner. But if Steinbrenner can take credit for that resurgence (as he would), he can (but will not, I am sure) take responsibility for the Yankees’ mediocrity from the early 1980s to early 1990s, and for their inability to win a World Series since 2000.

Anyway, the tale of the A’s, Senators/Twins, and Browns/O’s is this: persistent mediocrity and failure, punctuated by fleeting glory. The O’s came closest, of the three teams, to having a baseball dynasty (from the late 1960s to the early 1980s), but the Yankees they never were. The long periods of failure on the part of the A’s were self-inflicted in the days of Connie Mack‘s ownership. (Follow the link for more on that.) The failure of Washington’s baseball teams seems to be a law of nature, as evidenced by the records of the original Senators, the expansion Senators, and the Expos/Nationals, a.k.a Three Losers.

In the zero-sum game that is baseball, failure is self-inflicted. You either spend the money it takes to win, and spend it wisely, or you do not. Yes, the Yankees have loomed dominantly, most of the time, from the 1920s to the present. And, given that, some teams must have losing records. But why — so often and so persistently — have those teams been the A’s, Senators/Twins, and Browns/Orioles?

It almost makes me believe in destiny.

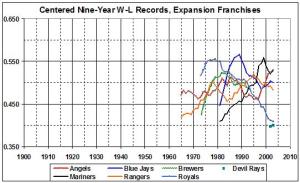

Remember, I am measuring performance over nine-year spans — not individual seasons — so the following lists will not always correspond with lists of teams having the best and worst W-L record, by season. Using the nine-year, I present the best (E = expansion team)…

Remember, I am measuring performance over nine-year spans — not individual seasons — so the following lists will not always correspond with lists of teams having the best and worst W-L record, by season. Using the nine-year, I present the best (E = expansion team)…