Paul Krugman is arguably a better advocate of regulation than a philosopher (unless the philosopher also has a Ph.D. in economics). But Krugman has met his match in Steven Landsburg, who slices and dices Krugman’s latest justification of the nanny state. Landsburg’s effort might render this post superfluous, but I began to write it before learning of the latest Krugman-Landsburg confrontation (the dénouement of an earlier one is here). There is more to be said and, unlike Landsburg, I am not a sucker for the concept that underpins regulation: the social welfare function (about which, see below).

IMPETUS

This post is inspired by Jason Brennan’s offering at the Bleeding Heart Libertarians blog, “A Simple Libertarian Argument for Environmental Regulation.” Brennan writes:

Libertarians are often very hostile to environmental regulation. Why? Reflecting on the argument below should help us understand their grounds and whether the grounds are any good.

1. Pollution and other kinds of environmental externalities impose costs upon others. A polluter forces others to bear the costs of his activities. Pollution tends to violate people’s property rights, as well as certain rights they have over themselves (such as the rights against having their health compromised against their will).

2. Government regulation of environmental issues is USUALLY/OFTEN/SOMETIMES effective, and is USUALLY/OFTEN/SOMETIMES more effective than using courts to defend the rights mentioned in premise 1. Courts are SOMETIMES/OFTEN/USUALLY ineffective in protecting these rights.

3. Therefore, government should have the right to issue environmental regulations in order to protect property rights, rights to life, and rights to health.

I don’t see how a libertarian could deny premise 1. So premise 2 does all the work. Premise 2 is an empirical premise. We can debate which word (“usually”, “often”, or “sometimes”) belongs in each sentence to make premise 2 true. However, unless the libertarian believes we should instead have “never” in the first sentence of premise 2, then it seems the libertarian has a strong case for favoring some government regulation of environmental issues….

Brennan is wrong to say that “premise 2 does all the work.” Premise 1 does just as much “work,” in a negative way, because it ignores positive externalities. Further, Brennan’s premise 2 omits to mention that regulation — however effectively it may address particular problems — is, on the whole, counterproductive. Brennan’s conclusion (#3) would be flawed, even if premises 1 and 2 were complete and correct, because it rests on the utilitarian presumption of a social welfare function.

In a follow-up post, “Objections to the Simple Libertarian Argument for Environmental Regulation,” Brennan writes:

[H]ere are some objections [to the earlier argument]:

A. The Mission Creep/Abuse Objection: Though 3 is true, if we give government the power to enforce the rights mentioned in 2 through environmental regulation, government will abuse and misuse this power. It will misuse/abuse it so much that it won’t be worth it. It’s better just to leave things to courts, and if that doesn’t work, just let people pollute.

B. The Cost-Benefit Objection: While government is sometimes effective at enforcing rights, cost-benefit analysis shows that the EPA and other such agencies, even when acting without abuse and in good faith, spend/cost far too much for every year of life saved. Against, it’s better just to leave things to courts or even just let people pollute.

C. Other Unintended Consequences Objection: Allowing government to try to solve the problem causes various other negative consequences, and isn’t worth the cost.

D. The Market Can Fix It Objection: There are some market-based (e.g., Coasean) means to solve these problems.

Having been thoroughly schooled in public choice and all the usual stuff, I see the point behind A-D. There’s significant truth behind each of these objections. However, if you’re one of those libertarians who believes the government should issue no environmental regulations (and many libertarians do believe this), you seem to me to be far too pessimistic about A-C and/or optimistic about D. Do the facts really turn out to imply that the optimal amount of government environmental regulation is none?

In the following sections, I expand on my statements about the premises (#1, #2) and conclusion (#3) of Brennan’s original post. Along the way, I address points A, B, C, and D of Brennan’s second post. I also address Brennan’s implicit assumption that regulators can arrive at an “optimal amount” of regulation. This is simply nonsense on stilts because, among other things, it contravenes “public choice,” in which Brennan claims to have been “thoroughly schooled.”

NOT ALL EXTERNALITIES ARE NEGATIVE

A polluter may be producing something that is of value not only to the purchasers of that product but also to others who derive benefits from the purchasers’ use of the product, benefits for which those others do not pay. In other words, negative externalities may be accompanied by positive externalities.

Consider electricity, which in the United States is generated mostly by fossil-fuel and nuclear-power plants. Coal-fired plants still generate about half of America’s electric power; nuclear plants account for another 20 percent. Both types of plants are perennial targets of environmental activists, who cavil at the emissions of coal-burning, the possibility of nuclear accidents, and the problem of containing or disposing of coal ash and radioactive waste. The stance of environmentalists — which is essentially the stance of the Environmental Protection Agency — is to reduce pollution and eliminate risk without regard for the positive externalities of power generation.

And those positive externalities are vast. The availability of electricity has made possible countless inventions and innovations, to the benefit of producers and consumers who did not pay a penny more to power companies for the benefits thus derived. Those inventions and innovations would not have been possible — and will not be possible — if not for the availability of electricity. To the extent that coal generation makes electricity cheaper and more widely available, it encourages beneficial inventions and innovations. One can say that a positive externality of coal-generated electricity has been a higher rate of economic growth — more jobs and greater prosperity — than would otherwise have been possible.

I have made a rough estimate of the value of the positive externalities of electrical power, as follows:

1. The tables for value added by industry at the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) website do not subdivide the utilities industry into categories (electric power, water, etc.). I therefore used the values given for the entire utilities industry as an upper bound of the value added by private electric-power companies. That value was 1.8 percent of GDP in 2008. Many governments (including the federal government) are in the power-generation business, but the value-added by government power utilities is not available, so I took as an upper bound the value added by government enterprises (federal, State, and local), which was 1.1 percent of GDP in 2008. Power-generating entities in the United States therefore add — at the very most — about 3 percent to the nation’s total economic output.

2. But the value added by power generation — something less than 3 percent of GDP, according to the BEA — fails to account for the fundamental importance of electric-power generation to America’s economy. It would not be a great exaggeration to say that the overnight loss of power-generating capacity would set the economy back to its status circa 1900. That was after factories had begun to use electricity but before it came into wide use in large cities. Real GDP per capita in 1900 was about 1/8 of the value it reached in 2008.

3. Try to think of an economic activity that does not depend on electricity. Given the pervasive dependence of all parts of the American economy on electricity, it would be difficult to deny that the power industry’s positive externality (its social return, if you will) is upwards of 7/8 of GDP, whereas the nominal value-added of electric power is less than 3 percent of GDP. That, my friends, is a positive externality to end all positive externalities.

REGULATION IS COUNTERPRODUCTIVE

Regulation is counterproductive for several reasons. First, it curtails positive externalities. Nothing more need be said on that score. The other reasons, on which I expand below, are that regulation cannot be contained to “good causes,” nor can it be tailored to do good without doing harm. These objections might be dismissed as trivial if regulatory overkill were rare and relatively costless, but it is pervasive, extremely costly its own right, and a major contributor to the economic devastation that has been wrought by the regulatory-welfare state.

Who Regulates the Regulators?

Regulators do not stop regulating when they (might) have done some good. Regulatory overreach is endemic to regulatory activity and cannot be separated from it. A lot of bad inevitably accompanies a bit of good. This happens because the regulatory agenda is driven by a combination of

- “activists” whose specific (and mostly aesthetic) objectives (kill the pipeline, don’t drill in ANWR, save the spotted owl, etc.) are intended to to limit economic activity and consumer choice;

- scientists who are eager to join the consensus about the latest environmental craze, just to be part of the action and also to grab their share of government-funded research — which, not coincidentally, tends to lend credence to the scare-of-the-month that justifies regulation;

- regulatory “capture,” through which incumbent firms “help” regulators in ways that favor incumbent firms and limit competition; and

- politicians and bureaucrats who play to “activists,” incumbent firms with deep pockets, and the general public (by claiming to be pro-environment), while extending their reach and power — because that is what politicians and bureaucrats like to do.

Regulation as a Blunt Instrument

Regulation substitutes one-size-fits all “solutions” for the tailored outcomes of free markets (including Coesean bargaining) and civil litigation. The result is a consistent pattern of government failure, which is amply documented. (See, for example, the 144 issues of Regulation that have been published to date.) Regulation might be defensible (though not by me) if it were a matter of occasional failure, but it is not. Resorting to regulation to “solve a problem” is like playing Russian roulette with five bullets in a six-shooter.

At its best, regulation mimics the results that would have obtained anyway, as seems to have been the case with automobile safety regulations. These did no more than allow the continuation of a long-running trend toward safer autos and highways, but at the cost of making autos less affordable for low-income persons.

At its worst, regulation prevents consumers from obtaining life-saving products. This can happen indirectly, through the generally stultifying effect of regulation on economic activity (estimated below). And it can happen directly, as with the Food and Drug Administration’s notorious record of delaying the availability of health- and life-saving medicines. (For more on the high cost of regulation, see W. Kip Viscusi and Ted Gayer’s “Safety at Any Price?” in Regulation, Fall 2002. For a good example of government imposing a dangerous one-size-fits-all burden on the populace, see Kenneth Anderson’s post, “The Science Is Settled: You’re Just Too Stupid to Live,” at The Volokh Conspiracy.)

A pervasive form of regulation, which usually is not labelled as such, is the Fed’s manipulation of interest rates and the supply of money. How has that worked out? Business cycles have become more volatile since the creation of the Fed in 1913. The worst downturn in American history — the Great Depression — can be chalked up, in large part, to the Fed’s loosening of credit in the late 1920s, followed by its contraction of the money supply in the early 1930s. We owe the Great Recession, which lingers, to the “perfect storm” of low interest rates (thanks to the Fed) and the regulation of housing markets (to encourage home-ownership by low-income persons) via Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Environmental regulation is no different than any other kind, resting as it does on aesthetic preferences, half-baked “scientific” theories (AGW being the latest and perhaps the most egregious of the lot), and the unholy alliance of “bootleggers and Baptists.” The “bootleggers” are incumbent firms; producers of “green” products and such-like; and politicians and bureaucrats, who stand to gain power and prestige from their “unselfish” efforts. The “Baptists” are smug do-gooders who just will not leave the rest of us alone to figure things out for ourselves.

The Interest-Group Paradox

Environmental regulation and regulation in general are integral to the vast and vastly destructive regulatory-welfare state that has rise up in America since the early 1900s. That growth is the result of a phenomenon which I call the interest-group paradox.

Pork-barrel legislation exemplifies the interest-group paradox in action, though the paradox involves more than pork-barrel legislation. There are myriad government programs that — like pork-barrel projects — are intended to favor particular classes of individuals. In the case of environmental regulation, the favored classes are “activists,” bureaucrats, incumbent firms, “green” enterprises, and the politicians who benefit from their symbiotic relationships with the aforementioned. The support for each program is “bought” at the expense of supporting other programs. Because there are thousands of government programs (federal, State, and local) — each intended to help a particular class of citizens (at the expense of others) — the net result is that almost no one in this fair land enjoys a “free lunch,” despite almost everyone’s efforts to do just that. This is the interest-group paradox.

The interest-group paradox is like the paradox of thrift, in that large numbers of individuals are trying to do something that makes certain classes of persons better off, but which in the final analysis makes those classes of persons worse off. It is also like the paradox of panic, in that there is a crowd of interest groups rushing toward a goal — a “pot of gold” — and (figuratively) crushing each other in the attempt to snatch the pot of gold before another group is able to grasp it. The gold that any group happens to snatch is a kind of fool’s gold: It passes from one fool to another in a game of beggar-thy-neighbor.

If you want regulation, you must pay the political price by backing other programs, for which you will seek payment in the form of additional regulation, and so on, ad perpetuum.

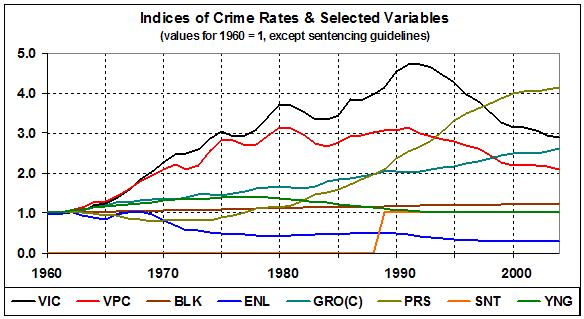

The Final Tally

The direct cost of regulation is about 10 percent of GDP: $1.5 trillion in today’s dollars. The indirect cost of regulation cannot be separated from the cumulative burden of the regulatory-welfare state. But that burden would not be as large as it is were it not for the integral role of environmental regulation in the working of the interest-group paradox. I have estimated that the establishment and expansion of the regulatory-welfare state over the past century has reduced real GDP by about 70 percent from the level it would have attained if the state had not been expanded beyond a “night watchman” role.

The price tag is so large that everyone (“activists,” regulators, etc.) pays in one way or another, through fewer choices, fewer jobs, and lower real incomes. And it cannot be otherwise because, as noted above, the bad inevitably comes with the good. To believe or claim otherwise is to indulge in the Nirvana fallacy and wishful thinking.

FUNDAMENTAL FLAW: THE MYTH OF THE SOCIAL-WELFARE FUNCTION

Costs aside, regulation is based on an epistemological error. The urge to regulate presumes a social welfare function that can be maximized — or improved, at least — by limiting the negative externalities that flow from certain economic activities.

For example, an environmental regulation might cause the owner of a polluting factory to buy and operate some kind of equipment that reduces the factory’s emissions. When the owner complies, those who live near the factory are presumed to be better off. And perhaps the benefits extend farther afield. But, in any case, the factory owner’s higher costs are likely to have untoward effects, for example, fewer jobs for factory workers and higher prices for the purchasers of the factory’s products.

When a proponent of regulation is confronted with this reality, he is likely to shrug and say that the costs (fewer jobs, higher prices) are worth the benefits (less pollution). Whence the moral authority to make that kind of judgment? It implies the existence of a social-welfare function, to which the proponent of regulation is privy.

This is nothing less than utilitarianism in the modern garb of cost-benefit analysis. The theory of cost-benefit analysis is simple: If the expected benefits from a government project or regulation are greater than its expected costs, the project or regulation is economically justified.

But cost-benefit analysis has a fundamental flaw, which it shares with utilitarianism: One person’s benefit cannot be compared with another person’s cost. (This objection vanishes when parties are free to engage in Coasean bargaining, but regulation preempts that option.) Suppose, for example, that the City of Los Angeles were to conduct a cost-benefit analysis which “proved” that the cost of constructing yet another freeway through the city would be more than offset (i.e., would yield a “net benefit”) because it would reduce the imputed cost of time spent in traffic by workers who drive into the city from the suburbs.

Yes, that is how cost-benefit analysis works. It assumes that the costs borne by one set of persons (taxpayers, consumers, unemployed factory workers, etc.) can be offset by the benefits that accrue to other persons (commuters, persons who live near factories, environmental “activists,”, etc.). It is the creed of “the greatest amount of happiness altogether.”

A moment’s reflection will tell you that there is no such thing as “the greatest amount of happiness altogether.” If A steals from B, A is happier for having obtained money with little effort, while B is less happy because he has less money. Does A’s gain in happiness cancel B’s loss of happiness. If you say “yes,” welcome to the world of psychopathy.

And you do say “yes,” implicitly, if you believe in environmental regulation — or any kind of regulation that effectively redistributes income or wealth.

THE ALTERNATIVES TO REGULATION: MARKETS AND COMMON LAW

Given all that I have said in the preceding sections, it seems clear that the burden of proof is (or should be) on those who wish to substitute regulation for markets and common law. It is also clear that, despite Brennan’s wishful thinking, government is incapable of delivering an “optimal amount” of regulation — whatever that might be. Markets may be imperfect (from the standpoint of the non-existent omniscient arbiter), but they are less imperfect than government.

General Arguments for Markets and Common Law Instead of Regulation

Is it wishful thinking to suppose that markets and civil litigation can deal with pollution and other kinds of negative externalities? Not at all:

Free-market environmentalism can also be expected to grow. It is the proven private alternative to costly and ineffective command-and-control schemes for protecting endangered species and habitats. To avoid the tragedy of the commons, one can look to the creation of more private, voluntary arrangements for “property rights” over animals, fish, and ecologically sensitive lands—via auctions of cleverly designed contracts to limit kills and catches and via binding covenants to preserve natural lands in perpetuity. Conservation banks, first created in 1995, now number 70 and represent another approach to environmental protection for endangered birds and animals. (Reason Foundation, “Transforming Government through Privatization,” Annual Privatization Report, 2006)

Terry L. Anderson, executive director of the Property & Environment Research Center (PERC) gives many examples of free-market environmentalism at work in “Markets and the Environment: Friends of Foes?” For much more, see PERC’s large catalog of publications. And PERC is but one of the many organizations doing serious scholarly work in the field of free-market environmentalism.

If you are old enough to remember the Love Canal disaster, you will assume (as I did) that it was the fault of the chemical company that had been dumping waste in the abandoned canal. Not so, according to Richard L. Stroup:

[L]iability for pollution is a powerful motivator when a factory or other potentially polluting asset is privately owned. The case of the Love Canal, a notorious waste dump, illustrates this point. As long as Hooker Chemical Company owned the Love Canal waste site, it was designed, maintained, and operated (in the late 1940s and 1950s) in a way that met even the Environmental Protection Agency standards of 1980. The corporation wanted to avoid any damaging leaks, for which it would have to pay.

Only when the waste site was taken over by local government—under threat of eminent domain, for the cost of one dollar, and in spite of warnings by Hooker about the chemicals—was the site mistreated in ways that led to chemical leakage. The government decision makers lacked personal or corporate liability for their decisions. They built a school on part of the site, removed part of the protective clay cap to use as fill dirt for another school site, and sold off the remaining part of the Love Canal site to a developer without warning him of the dangers as Hooker had warned them. The local government also punched holes in the impermeable clay walls to build water lines and a highway. This allowed the toxic wastes to escape when rainwater, no longer kept out by the partially removed clay cap, washed them through the gaps created in the walls….

Nor does the government sector have the long-range view that property rights provide, which leads to protection of resources for the future. As long as … divestibility, is present, property rights provide long-term incentives for maximizing the value of property. If I mine my land and impair its future productivity or its groundwater, the reduction in the land’s value reduces my current wealth. That is because land’s current worth equals the present value of all future services. Fewer services or greater costs in the future mean lower value now. In fact, on the day an appraiser or potential buyer can first see that there will be problems in the future, my wealth declines. The reverse also is true: any new way to produce more value—preserving scenic value as I log my land, for example, to attract paying recreationists—is capitalized into the asset’s present value.

Because the owner’s wealth depends on good stewardship, even a shortsighted owner has the incentive to act as if he or she cares about the future usefulness of the resource. This is true even if an asset is owned by a corporation. Corporate officers may be concerned mainly about the short term, but as financial economists such as Harvard Business School’s Michael C. Jensen have noted, even they have to care about the future. If current actions are known to cause future problems, or if a current investment promises future benefits, the stock price rises or falls to reflect the change. Corporate officers are informed by (and are judged by) these stock price changes. (From “Free Market Environmentalism,” at the Library of Economics and Liberty.)

The Siren Song of Government Intervention

Stroup stumbles, however, by saying that

when many polluters and those who receive the pollution are involved, how can property rights force accountability? The nearest receivers may be hurt the most, and may be able to sue polluters—but not always. Consider an extreme case: the potential global warming impact of carbon dioxide produced by the burning of wood or fossil fuels. If climate change results, the effects are worldwide. Nearly everyone uses the energy from such fuels, and if the threat of global warming from a buildup of carbon dioxide turns out to be as serious as some claim, then those harmed by global warming will be hard-pressed to assert their property rights against all the energy producers or users of the world. The same is true for those exposed to pollutants produced by autos and industries in the Los Angeles air basin. Private, enforceable, and tradable property rights can work wonders, but they are not a cure-all.

If a cure-all is required, one ought to pray for miracles. Short of miracles, the question is whether it is better to rely on government action or voluntary action, supplemented by civil litigation. I say “or” precisely because government action precludes the alternatives. It is “better” to rely on government if one wants a dictated outcome, is willing to impose the costs of attaining that outcome on persons who are not involved in the situation at hand (e.g., distant taxpayers), and is indifferent to the unintended consequences of government action. It is better to rely on voluntary action, supplemented by civil litigation, if one cares about liberty and economic efficiency (as found in Coasean solutions to conflicts of interest).

Taking smog in the L.A. basin first: It belongs to that class of “problem” which includes choosing to live in areas that are prone to hurricanes, floods, and fires. The obvious voluntary solution — for those who find smog, etc., not worth whatever benefits may accrue to living with it (e.g., higher income) — is to quit the locale. Along comes government to impose one-size-fits-all solutions that also impose costs on persons who do not live in areas where there is smog, etc. The immediate results of government intervention are a disincentive to move and massive subsidization of those who choose not to move by persons who have their own problems to contend with. Further results are

- disincentives to entrepreneurs who would come forward with ameliorative devices (e.g., air-filtration systems and catalytic converters);

- disincentives to persons of a charitable bent who would take it upon themselves to help low-income persons afford ameliorative devices and even help to underwrite the development of such devices;

- moral hazard, that is, putting the non-movers in a position to incur further losses that will be subsidized; and

- the playing out of the interest-group paradox, wherein those who are subsidized agree (tacitly) to subsidize persons who seek subsidization or other favors from government.

Entrepreneurship is thought to be unlikely (in the circumstance) because of the free-rider problem, but the free-rider problem is overstated. Further, charity (giving without the expectation of more than psychic return) is one proof against the presumption of economic paralysis that is embedded in the statement of the free-rider problem.

Regardless of the arguments against regulation, most politicians and left-wingers would say that it is proper to respond “collectively” to pollution because, after all, that is the hallmark of a “just, caring society,” in which “we” take care of each other. Are disincentives to entrepreneurship, charity, moral hazard, cross-subsidization, and plain old theft by government really the hallmarks of a “just, caring society”? Not at all; they are the facts of life that politicians and leftists prefer to ignore because they prefer collective action (at the point of government’s gun) to effective action. The invocation of a “just, caring society” is a cheap political trick, played by leftists and politicians. In the case of politicians, it is a sign of (cheap) compassion that helps them win elections, feed at the public trough, and slake their power-lust.

No “Problem” Is Too Big for Private Action

Stroup, despite his evident understanding of the power of markets to solve “problems,” seems to hold a viewpoint in common with knee-jerk advocates of government action: If a “problem” exists, it is only a “problem,” not an incidental, negative aspect of beneficial activity. And its “solution” cannot come at too high a price, that is, whatever price government imposes through regulation, inasmuch as “optimal regulation” is a pipe-dream.

Moreover, the “problem” may be so pervasive that only government can solve it. Why? Because those who suffer negative externalities are unable to bargain with or take legal action against the parties responsible for the externalities. Who are those parties? They are us! We — the users of electricity and the many other products and services whose creation results in the emission of carbon dioxide — may be joined in an unwitting suicide pact, despite the warnings of “seers” like Al Gore, James Hansen, Michael Mann, et al.. Those warnings (blatantly hypocritical in Gore’s case) amount to this: “We” (but not “they”) must surrender a large portion of the material gains that have been wrested from nature through ingenuity and industriousness; otherwise, there will be dire consequences for all. (Perhaps it would have been better if our distant ancestors had not learned how to make fire, with all of its dire consequences for humans and their possessions.)

I have written so much about the issue of AGW (e.g., here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here) that I will not bother to address its validity here. I will assume, merely for the sake of argument, that it is a possibility. But saying that it is a possibility does not mean that it is a dire emergency. Consider, for example, these excerpts of Nobel laureate Ivar Ginever’s letter of resignation from the American Physical Society:

In the APS it is ok to discuss whether the mass of the proton changes over time and how a multi-universe behaves, but the evidence of global warming is incontrovertible? The claim (how can you measure the average temperature of the whole earth for a whole year?) is that the temperature has changed from ~288.0 to ~288.8 degree Kelvin in about 150 years, which (if true) means to me is that the temperature has been amazingly stable, and both human health and happiness have definitely improved in this ‘warming’ period.

If AGW is truly a problem — and not just a “problem” that “demands” government action — it is evidently not an emergency that requires immediate, concerted action by a central authority. To the contrary, if it is a problem it can be addressed by a variety of voluntary actions. These include the gradual migration of heat-sensitive individuals and economic activities to cooler parts of the globe and the development and spread of ameliorative technologies for those persons and activities that cannot or will not migrate. All such adaptive behavior will become more possible and affordable if economic growth is not choked off by regulations that arbitrarily stifle economic activity by curbing the emission of so-called greenhouse gases. (That a large proportion of individuals and economic activities would thrive as their environment warms a bit seems to be lost on climate-change alarmists.)

If the possibility of AGW does not justify government action, what about a true global emergency? Imagine, for example, that reputable scientists around the globe detect a large asteroid that is almost certain to strike Earth in two years, and that the likely result of the strike is the end of human life on the planet. Would that not justify concerted government action?

Again, I say “no.” What it would justify — and encourage — is action by independent (but possibly cooperative) teams of scientists and engineers, underwritten by various groups of super-rich individuals and large corporations. Why should such individuals and corporations fund an effort that would benefit upward of seven billion free riders? Because the existence of those individuals and corporations would be at stake, and many of them would welcome the glory and/or increased sales that would undoubtedly accompany a successful anti-asteroid operation.

I refer you, again, to my earlier post about the free-rider problem, and the link that is embedded in the post. In both posts, I argue that defense and justice — among other so-called public goods — are nothing of the kind. They are goods that, in a relatively open polity like that of the United States, are better provided by an accountable state than entrusted to competing private entities. It should be obvious — and it is obvious to all but obdurate anarcho-capitalists — that such entities would be the equivalent of warlords. The law of the jungle would replace the rule of law. That possibility is the only excuse for the state’s monopolization of justice and defense. But nothing — not even “externalities” — excuses the state’s intrusion into economic activity that is peaceful and voluntary.

Related posts:

Fear of the Free Market — Part I

Fear of the Free Market — Part II

Fear of the Free Market — Part III

The Social Welfare Function

Risk and Regulation

A Short Course in Economics

The Interest-Group Paradox

Addendum to a Short Course in Economics

Utilitarianism, “Liberalism,” and Omniscience

Accountants of the Soul

Ricardian Equivalence Reconsidered

The Real Burden of Government

Utilitarianism vs. Liberty

Toward a Risk-Free Economy

Rawls Meets Bentham

The Rahn Curve at Work

The Case of the Purblind Economist

The Illusion of Prosperity and Stability

Estimating the Rahn Curve: Or, How Government Inhibits Economic Growth

Luck-Egalitariansim and Moral Luck

Understanding Hayek

The Destruction of Society in the Name of “Society”

What Free-Rider Problem?

Human Nature, Liberty, and Rationalism

Utilitarianism and Psychopathy