UPDATED BELOW, 06/23/07

According to the lists of movies that I keep at the Internet Movie Database (IMDb), I have thus far seen 2,034 theatrically released feature films in my lifetime. That number does not include such forgettable fare as the grade-B westerns, war movies, and Bowery Boys comedies that I saw on Saturdays, at two-for-a-nickel, during my pre-teen years.

I have given 570 (28 percent) of those 2,034 films a rating of 8, 9, or 10 (out of 10). The proportion of high ratings does not indicate low standards on my part; rather, it indicates the care with which I have (usually) selected films for viewing.

I call the 570 highly rated films my favorites. I won’t list all them here, but I will mention some of them — and their stars — as I analyze the up-and-down history of film-making.

I must, at the outset, admit two biases that have shaped my selection of favorite movies. First, because I’m a more or less typical American movie-goer (or movie-viewer, since the advent of cable, VCR, and DVD), my list of favorites is dominated by American films starring American actors.

A second bias is my general aversion to silent features and early talkies. Most of the directors and actors of the silent era relied on “stagy” acting to compensate for the lack of sound — a style that persisted into the early 1930s. There are exceptions, of course. Consider Charlie Chaplin, whose genius as a director and comic actor made a virtue of silence; my list of favorites includes two of Chaplin’s silent features (The Gold Rush, 1925) and (City Lights, 1931). Perhaps a greater comic actor (and certainly a more physical one) than Chaplin was Buster Keaton, whose Our Hospitality (1923), The Navigator (1924), Sherlock Jr. (1924), The General (1927), and Steamboat Bill Jr. (1928) outnumber Chaplin’s contributions to my favorites. My list of favorites includes only ten other films from the years before 1933, among them F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu the Vampire (1922) and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) — the themes of which (supernatural and futuristic, respectively) enabled them to transcend the limitations of silence — and such early talkies as Whoopee! (1930), Dracula (1931), and Grand Hotel (1932).

On the whole, I can recall having seen only 42 feature films that were released before 1933, 17 of which (40 percent) rank among my favorites. (I plan, however, to increase that number as I sample other highly rated silent films, including several of Harold Lloyd’s.) So, I will say no more here about films released before 1933. I will focus, instead, on movies released from 1933 to the present — which I consider the “modern” era of film-making.

My inventory of modern films comprises 1,992 titles, of which I have rated 553 at 8, 9, or 10 on the IMDb scale. But the overall proportion of favorites (28 percent) masks vast differences in the quality of modern films, which were produced in three markedly different eras:

- the Golden Age (1933-1942) — 179 films seen, 96 favorites (54 percent)

- the Abysmal Years (1943-1965) — 317 films seen, 98 favorites (31 percent)

- the Vile Years (1966-present) — 1,496 films seen, 359 favorites (24 percent)

What made the Golden Age golden, and why did films go from golden to abysmal to vile? Read on.

To understand what made the Golden Age golden, let’s consider what makes a great movie: a novel or engaging plot, dialogue that is fresh if not witty, and strong performances (acting, singing, and/or dancing). (A great animated feature may be somewhat weaker on plot and dialogue if the animations and sound track are first rate.) The Golden Age was golden largely because the advent of sound fostered creativity — plots could be advanced through dialogue, actors could deliver real dialogue, and singers and dancers could sing and dance with abandon. It took a few years to fully realize the potential of sound, but movies hit their stride just as the country was seeking respite from worldly cares: first, a lingering and deepening Depression, then the growing certainty of war.

Studios vied with each other to entice movie-goers with new plots (or plots that seemed new when embellished with sound), fresh and often wickedly witty dialogue, and — perhaps most important of all — captivating performers. The generation of super-stars that came of age in the 1930s consisted mainly of handsome men and beautiful women, blessed with distinctive personalities, and equipped by their experience on the stage to deliver their lines vibrantly and with impeccable diction.

What were the great movies of the Golden Age, and who starred in them? Here’s a sample of the titles: 1933 — Dinner at Eight, Flying Down to Rio, Morning Glory; 1934 — It Happened One Night, The Thin Man, Twentieth Century; 1935 — Mutiny on the Bounty, A Night at the Opera, David Copperfield; 1936 — Libeled Lady, Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, Show Boat; 1937 — The Awful Truth, Captains Courageous, Lost Horizon; 1938 — The Adventures of Robin Hood, Bringing up Baby, Pygmalion; 1939 — Destry Rides Again, Gunga Din, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Wizard of Oz, The Women; 1940 — The Grapes of Wrath, His Girl Friday, The Philadelphia Story; 1941 — Ball of Fire, The Maltese Falcon, Suspicion; 1942 — Casablanca, The Man Who Came to Dinner, Woman of the Year.

And who starred in the greatest movies of the Golden Age? Here’s a goodly sample of the era’s superstars, a few of whom came on the scene toward the end: Jean Arthur, Fred Astaire, John Barrymore, Lionel Barrymore, Ingrid Bergman, Humphrey Bogart, James Cagney, Claudette Colbert, Ronald Colman, Gary Cooper, Joan Crawford, Bette Davis, Irene Dunne, Nelson Eddy, Errol Flynn, Joan Fontaine, Henry Fonda, Clark Gable, Cary Grant, Jean Harlow, Olivia de Havilland, Katharine Hepburn, William Holden, Leslie Howard, Allan Jones, Charles Laughton, Carole Lombard, Myrna Loy, Jeanette MacDonald, Joel McCrea, Merle Oberon, Laurence Olivier, William Powell, Ginger Rogers, Rosalind Russell, Norma Shearer, Barbara Stanwyck, James Stewart, and Spencer Tracy. There were other major stars, and many popular supporting players, but it seems that a rather small constellation of superstars commanded most of the leading roles in the best movies of the Golden Age — most of the great movies and many others of merit.

Why did movies go into decline after 1942’s releases? World War II certainly provided an impetus for the end of the Golden Age. The war diverted resources from the production of major theatrical films; grade-A features gave way to low-budget fare. And some of the superstars of the Golden Age went off to war. (Two who remained civilians — Leslie Howard and Carole Lombard — were killed during the war.) With the resumption of full production in 1946, the surviving superstars who hadn’t retired were fading fast, though their presence still propelled many a movie. In fact, superstars of the Golden Age starred in 44 of my 98 favorites from the Abysmal Years but only two of my 359 favorites from the Vile Years.

Stars come and go, however, as they have done since Shakespeare’s day. The Abysmal and Vile Years have deeper causes than the dimming of old stars:

- The Golden Age had deployed all of the themes that could be used without explicit sex, graphic violence, and crude profanity — none of which become an option for American movie-makers until the mid-1960s.

- Prejudice got significantly more play after World War II, but it’s a theme that can’t be used very often without boring audiences.

- Other attempts at realism (including film noir) resulted mainly in a lot of turgid trash laden with unrealistic dialogue and shrill emoting — keynotes of the Abysmal Years.

- Hollywood productions sank to the level of TV, apparently in a misguided effort to compete with that medium. The garish technicolor productions of the 1950s often highlighted the unnatural neatness and cleanliness of settings that should have been rustic if not squalid.

- The transition from abysmal to vile coincided with the cultural “liberation” of the mid-1960s, which saw the advent of the “f” word in mainstream films. Yes, the Vile Years have brought us more more realistic plots and better acting (thanks mainly to the Brits). But none of that compensates for the anti-social rot that set in around 1966: drug-taking, drinking and smoking are glamorous; profanity proliferates to the point of annoyance; sex is all about lust and little about love; violence is gratuitous and beyond the point of nausea; corporations and white, male Americans with money are evil; the U.S. government (when Republican-controlled) is in thrall to that evil; etc., etc. etc.

There have been, of course, outbreaks of greatness since the Golden Age. During the Abysmal Years, for example, aging superstars appeared in such greats as Life With Father (Dunne and Powell, 1947), Key Largo (Bogart and Lionel Barrymore, 1948), Edward, My Son (Tracy, 1949), The African Queen (Bogart and Hepburn, 1951), High Noon (Cooper, 1952), Mr. Roberts (Cagney, Fonda, Powell, 1955), The Old Man and the Sea (Tracy, 1958), Anatomy of a Murder (Stewart, 1959), North by Northwest (Grant, 1959), Inherit the Wind (Tracy, 1960), Long Day’s Journey into Night (Hepburn, 1962), Advise and Consent (Fonda and Laughton, 1962), The Best Man (Fonda, 1964), and Othello (Olivier, 1965). A new generation of stars appeared in such greats as The Lavender Hill Mob (Alec Guinness, 1951), Singin’ in the Rain (Gene Kelly, 1952), The Bridge on the River Kwai (Guiness, 1957), The Hustler (Paul Newman, 1961), Lawrence of Arabia (Peter O’Toole, 1962), and Dr. Zhivago (Julie Christie, 1965). Even Lancaster (Elmer Gantry, 1960) , Kerr (The Innocents, 1962), and Peck (To Kill a Mockingbird, 1962) had their moments. Nevertheless, selecting a movie at random from the output of the Abysmal Years — in the hope of finding something great or even worth watching — is like playing Russian Roulette with a loaded revolver.

The same can be said for the Vile Years, which in spite of their seaminess have yielded many excellent films and new stars. Some of the best films (and their stars) are A Man for All Seasons (Paul Scofield, 1966), Midnight Cowboy (Dustin Hoffman, 1969), MASH (Alan Alda, 1970), The Godfather (Robert DeNiro, 1972), Papillon (Hoffman, Steve McQueen, 1973), One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Jack Nicholson, 1975), Star Wars and its sequels (Harrison Ford, 1977, 1980, 1983), The Great Santini (Robert Duvall, 1979), The Postman Always Rings Twice (Nicholson, Jessica Lange, 1981), The Year of Living Dangerously (Sigourney Weaver, Mel Gibson, 1982), Tender Mercies (Duvall, 1983), A Room with a View (Helena Bonham Carter, Daniel Day Lewis 1985), Mona Lisa (Bob Hoskins, 1986), Fatal Attraction (Glenn Close, 1987), 84 Charing Cross Road (Anne Bancroft, Anthony Hopkins, Judi Dench, 1987), Dangerous Liaisons (John Malkovich, Michelle Pfeiffer, 1988), Henry V (Kenneth Branagh, 1989), Reversal of Fortune (Close and Jeremy Irons, 1990), Dead Again (Branagh, Emma Thompson, 1991), The Crying Game (1992), Much Ado about Nothing (Branagh, Thompson, Keanu Reeves, Denzel Washington, 1993), Trois Couleurs: Bleu (Juliette Binoche, 1993), Richard III (Ian McKellen, Annette Bening, 1995), Beautiful Girls (Natalie Portman, 1996), Comedian Harmonists (1997), Tango (1998), Girl Interrupted (Winona Ryder, 1999), Iris (Dench, 2000), High Fidelity (John Cusack, 2000), Chicago (Renee Zellweger, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Richard Gere, 2002), Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (Russell Crowe, 2003), Finding Neverland (Johnny Depp, Kate Winslet, 2004), Capote (Philip Seymour Hoffman, 2005), The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (2005), The Painted Veil (Edward Norton, Naomi Watts, 2006), and Breach (Chris Cooper, 2007).

But every excellent film produced during the Abysmal and Vile Years has been surrounded by outpourings of dreck, schlock, and bile. The generally tepid effusions of the Abysmal Years were succeeded by the excesses of the Vile Years: films that feature noise, violence, sex, and drugs for the sake of noise, violence, sex, and drugs; movies whose only “virtue” is their appeal to such undiscerning groups as teeny-boppers, wannabe hoodlums, resentful minorities, and reflexive leftists; movies filled with “bathroom” and other varieties of “humor” so low as to make the Keystone Cops seem paragons of sophisticated wit.

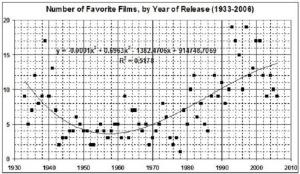

In sum, movies have become progressively worse than ever since the end of the Golden Age — and I have the numbers to prove it. The numbers are based on my IMDb ratings, and my conclusion about the low estate of film-making flows from those ratings. That is to say, I came to the conclusion that the quality of films has been in decline since 1942 only after having rated some 2,000 films. Before I looked at the numbers I believed that there had been a renaissance in film-making, inasmuch as the number of highly rated films (favorites), has been rising since the latter part of the Abysmal Years:

But the rising number of favorites is due to the rising number of films (mainly recent releases) that I have seen since the advent of VHS and DVD (and especially since my retirement about 10 years ago). In the chart below, all of the points to the right of 30 on the x-axis represent films released in 1982 or later; all of the points to the right of 60 represent films released in 1994 or later. (I have omitted the releases of 2007 from this analysis because I have seen only one of them: Breach.)

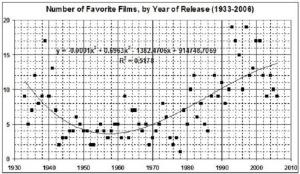

Those observations led to me to run a regression films released from 1933 through 2006. The result:

Number of favorite films (for a given year of release) = 147.94 – (o.075 x year) + (0.24 x number of films seen)

Regression statistics: adjusted r-square — 0.66; standard error of estimate — 2.61; F — 72.52; t values of intercept and independent variables — 3.46, 3.40, 10.06

By applying the regression equation to the number of films seen in each year I could compare the actual and predicted number of favorites as a percentage of films seen:

By applying the regression equation to the number of films seen in each year I could compare the actual and predicted number of favorites as a percentage of films seen:

The downward trend is unmistakable, both in the data and in the predictions:

- Actual percentages for seven of the 10 years of the Golden Age exceed predictions for those years.

- Actual percentages fall short of predicted percentages in 18 of the 23 Abysmal Years — evidence of the general dreariness of the films of that era.

- The Vile Years have had their high points and low points — both mainly in the 1960s and ’70s — but, nevertheless, the downward trend since the Golden Age continues unabated.

Imagine how much steeper the downward trend would be if my observations were to include absolute trash of the sort that dominates the trailers which one encounters on TV and DVDs. My selectivity in movie-watching has led me to overstate the quality of recent and current movie offerings.

Movies are worse than ever, but there are gems yet to be found among the dross.

UPDATE: The lowest IMDb rating for a movie is a “1” — a rating that I have given to 37 films. Those 37 are the movies that I found too moronic or vile to watch to the end. The following table lists the films, shows my ratings, and shows the average ratings assigned by users of IMDb. It is telling that (with three exceptions) the average ratings range from 6.6 to 8.2 — relatively high scores in the world of IMDb.

By applying the regression equation to the number of films seen in each year I could compare the actual and predicted number of favorites as a percentage of films seen:

By applying the regression equation to the number of films seen in each year I could compare the actual and predicted number of favorites as a percentage of films seen: