Michael Shermer writes about political philosophy and human nature in “Liberty and Science” at Cato Unbound:

In the Realistic Vision, human nature is relatively constrained by our biology and evolutionary history, and therefore social and political systems must be structured around these realities, accentuating the positive and attenuating the negative aspects of our natures. A Realistic Vision rejects the blank slate model that people are so malleable and responsive to social programs that governments can engineer their lives into a great society of its design, and instead believes that family, custom, law, and traditional institutions are the best sources for social harmony. The Realistic Vision recognizes the need for strict moral education through parents, family, friends, and community because people have a dual nature of being selfish and selfless, competitive and cooperative, greedy and generous, and so we need rules and guidelines and encouragement to do the right thing….

[T]he evidence from psychology, anthropology, economics, and especially evolutionary theory and its application to all three of these sciences supports the Realistic Vision of human nature….

6. The power of family ties and the depth of connectedness between blood relatives. Communities have tried and failed to break up the family and have children raised by others; these attempts provide counter evidence to the claim that “it takes a village” to raise a child. As well, the continued practice of nepotism further reinforces the practice that “blood is thicker than water.”

7. The principle of reciprocal altruism—I’ll scratch your back if you’ll scratch mine”—is universal; people do not by nature give generously unless they receive something in return, even if what they receive is social status.

8. The principle of moralistic punishment—I’ll punish you if you do not scratch my back after I have scratched yours—is universal; people do not long tolerate free riders who continually take but almost never give….

11. The almost universal nature of within-group amity and between-group enmity, wherein the rule-of-thumb heuristic is to trust in-group members until they prove otherwise to be distrustful, and to distrust out-group members until they prove otherwise to be trustful.

12. The almost universal desire of people to trade with one another, not for the selfless benefit of others or the society, but for the selfish benefit of one’s own kin and kind; it is an unintended consequence that trade establishes trust between strangers and lowers between-group enmity, as well as produces greater wealth for both trading partners and groups.

So far, so good. But Shermer then goes off track: “I believe that the Realistic Vision of human nature is best represented by the libertarian political philosophy….” He defines that philosophy earlier:

Libertarianism is grounded in the Principle of Equal Freedom: All people are free to think, believe, and act as they choose, so long as they do not infringe on the equal freedom of others. Of course, the devil is in the details of what constitutes “infringement”….

(See also the Harm Principle, which is a corollary of the Principle of Equal Freedom.)

Yes, the devil is in the details, as Will Wilkinson explains in “The Indeterminacy of Political Philosophy“:

[E]very conception of freedom or liberty when stated in broad outlines is relatively indeterminate. In order to arrive at a recognizably “libertarian” version of a conception of freedom requires filling out the conception in not-at-all obvious ways. This is true even of the classic libertarian conception of liberty as non-coercion. Generally, libertarians rely on a tendentiously loaded conception of coercion that simply stipulates that commonsense forms of emotional, psychological, and social coercion aren’t really coercive in the relevant sense.

Wilkinson goes too far when he indicts “emotional, psychological, and social coercion,” which he does at greater length here. It would not be far-fetched to say that Wilkinson finds coercion everywhere, even in the exercise of property rights, which are so well established that only a Marxist (I had thought) would consider them an instrument of coercion. It seems that Wilkinson — like most of the so-called libertarians who frequent the internet — yearns for super-human beings who are devoid of basic human traits and impulses.

The fact is that — psychopaths and dictators excepted — we are all “coerced,” not in Wilkinson’s sense of the word but in the sense that we must often constrain our behavior and make compromises with others (i.e., become “socialized”) if we are to live in liberty. This is a point that I made in my first post at this blog (“On Liberty“), and which I have repeated many times:

[T]he general observance of social norms … enables a people to enjoy liberty, which is:

peaceful, willing coexistence and its concomitant: beneficially cooperative behavior

That, simply stated, is liberty or something as close to it as can be found on Earth.

Peaceful, willing coexistence and beneficially cooperative behavior can occur only among actual human beings, with all of their inborn traits and impulses. Yes, peaceful coexistence requires human beings to curb those traits and impulses, to some degree, but those traits and impulses cannot be suppressed entirely. If they could, there would be no need for discussions of this kind: “When men are pure, laws are useless….” (Benjamin Disraeli).

And so, coexistence is shaped by human traits and impulses, just as spacetime is shaped by the masses of gravitational bodies. The conditions of coexistence are as inseparable from human nature as the curvature of spacetime is from its contents. If liberty is to be more than a slogan, it must account for human beings as they really are. That is to say, liberty must account for human beings as Michael Shermer describes them. Thus:

- Liberty is a modus vivendi, not a mysterious essence with an independent, timeless existence (like a Platonic ideal).

- Liberty arises from in-group solidarity, which is based on shared customs, beliefs (including religious ones), and a moral code that defines harmful acts and requires voluntary, peaceful cooperation among members of the group. (This means that there are many groups whose customs, beliefs, and moral codes are not libertarian, even though such groups may evince solidarity and cooperation.)

- Liberty is possible (but problematic) where there are many such interconnected groups under the aegis of a minimal state — one that exacts justice for acts that all groups consider harmful (e.g., murder, theft, rape), keeps the peace among groups, and protects all groups from external predators. (The federalism of the original Constitution fostered liberty, but only to the extent that individual States enforced their Bills of Rights, enabled local governance, and forbade slavery.)

- By virtue of geography, a state’s client groups may include some that are predatory, either economically and socially (seeking subsidies and other privileges) or criminally (acting violently toward other groups and their members). A minimal state that is dedicated to liberty will deny privileges and give no quarter to violence.

- Resistance to trade and immigration across international boundaries — as social stances taken in full knowledge of the potential benefits of trade and immigration — are legitimate political positions, except when they are held by trade unionists and their political allies, who seek to deprive other Americans of the benefits of trade and immigration. (Economists who presume to lecture about the wisdom of trade and immigration are guilty of reducing what can be deep social issues to shallow economic ones.)

- Because liberty is a manifestation of in-group solidarity, it is legitimate for groups that are comprised in a state to question and resist actions by the state that require the acceptance, on equal terms, of persons and groups (a) whose mores are not in keeping with those of extant groups and (b) whose influence could result in the enforcement by the state of anti-libertarian measures.

- Liberty, in a phrase, begins “at home” (the state willing) and extends only as far as the social boundaries of a group that coheres in mutual trust, respect, forbearance, and aid. There is a slim possibility of state-fostered liberty, but it can realized only where the state exacts justice for acts that all groups consider harmful, keeps the peace among groups, and protects all groups from external predators. (In those respects, there is a promise of liberty — but a promise not kept — in the Constitution of the United States.)

- But liberty is less likely to be found “at home” (or anywhere) because the social fabric has been sundered by the state’s impositions (e.g., usurping charitable functions and discouraging them by progressive taxation, the anti-religion trajectory of judicial holdings, the undermining of swift and sure justice by outlawing the death penalty and making it difficult to enforce, allowing abortion that borders on infanticide, mocking and undermining the institution of marriage).

Liberty, in other words, is a product of social intercourse, not of abstract principles, and certainly not of ratiocination. The last-mentioned, which often yields agreement between “liberals” and “libertarians” on such matters as abortion, defense, immigration, and homosexual “marriage,” also finds them deeply divided on such matters as property rights, regulation, and various forms of redistribution (Social Security, Medicare, humanitarian aid in the U.S. and overseas, and so on). Ratiocination, in other words, is unlikely to transcend the temperament of the ratiocinator. (Wilkinson essentially agrees, in “The Indeterminacy of Political Philosophy,” but seems not to heed himself.)

To put it another way, the desirability or undesirability of state action has nothing to do with the views of “liberals,” “libertarians,” or any set of pundits, “intellectuals,” “activists,” and seekers of “social justice.” As such, they have no moral standing, which one acquires only by being — and acting as — a member of a cohesive social group with a socially evolved moral code that reflects the lessons of long coexistence. The influence of “intellectuals,” etc., derives not from the quality of their thought or their moral standing but from the influence of their ideas on powerful operatives of the state.

In short, the only truly libertarian intellectual stance is anti-rationalism. As Michael Oakeshott explains, a rationalist

never doubts the power of his ‘reason … to determine the worth of a thing, the truth of an opinion or the propriety of an action. Moreover, he is fortified by a belief in a ‘reason’ common to all mankind, a common power of rational consideration….

… And having cut himself off from the traditional knowledge of his society, and denied the value of any education more extensive than a training in a technique of analysis, he is apt to attribute to mankind a necessary inexperience in all the critical moments of life, and if he were more self-critical he might begin to wonder how the race had ever succeeded in surviving. (“Rationalism in Politics,” pp. 5-7, as republished in Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays)

An anti-rationalist refuses to view life through the formalistic lens of “rights, freedoms and personal empowerment,” to lift a phrase from Leon Kass’s “The Wisdom of Repugnance.” An anti-rationalist trusts the wisdom that is accrued in social norms, and thinks very carefully before trying to change those norms. As Kass puts it, in the context of cloning,

repugnance is the emotional expression of deep wisdom, beyond reason’s power fully to articulate it….

Repugnance … revolts against the excesses of human willfulness, warning us not to transgress what is unspeakably profound. Indeed, in this age in which everything is held to be permissible so long as it is freely done, in which our given human nature no longer commands respect, in which our bodies are regarded as mere instruments of our autonomous rational wills, repugnance may be the only voice left that speaks up to defend the central core of our humanity. Shallow are the souls that have forgotten how to shudder.

Related posts:

On Liberty

What Is Conservatism?

Utilitarianism, “Liberalism,” and Omniscience

Utilitarianism vs. Liberty

The Principles of Actionable Harm

The Indivisibility of Economic and Social Liberty

Negative Rights

Negative Rights, Social Norms, and the Constitution

Rights, Liberty, the Golden Rule, and the Legitimate State

Accountants of the Soul

The Unreality of Objectivism

“Natural Rights” and Consequentialism

Rawls Meets Bentham

More about Consequentialism

Rationalism, Social Norms, and Same-Sex “Marriage”

Inside-Outside

A Moralist’s Moral Blindness

Society and the State

Undermining the Free Society

Pseudo-Libertarian Sophistry vs. True Libertarianism

Positivism, “Natural Rights,” and Libertarianism

“Intellectuals and Society”: A Review

What Are “Natural Rights”?

The Golden Rule and the State

Government vs. Community

Libertarian Conservative or Conservative Libertarian?

Bounded Liberty: A Thought Experiment

Evolution, Human Nature, and “Natural Rights”

More Pseudo-Libertarianism

More about Conservative Governance

The Meaning of Liberty

Positive Liberty vs. Liberty

On Self-Ownership and Desert

In Defense of Marriage

Understanding Hayek

The Destruction of Society in the Name of “Society”

The Golden Rule as Beneficial Learning

Facets of Liberty

Burkean Libertarianism

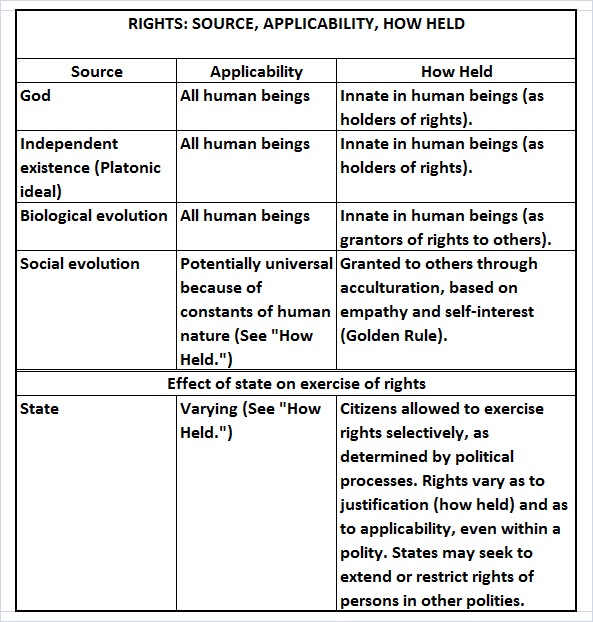

Rights: Source, Applicability, How Held

What Is Libertarianism?

Nature Is Unfair

True Libertarianism, One More Time