The length of “Evolution, Human Nature, and ‘Natural Rights’” seems to have discouraged readers. In the hope of enticing you to venture below the fold, I have annotated the outline that appears above the fold. Also, there is now a direct link to the 31 related posts that are listed and linked to at the bottom of “Evolution, Human Nature, and ‘Natural Rights’.”

Category: Science and Understanding

Government Failure: An Example

John Goodman’s post about “Government Failure” is chock-full of wisdom. Among other things, Goodman nails the model of “market failure” used by some economists and many politicians:

When economists talk about “market failure” they begin with a model in which consumer welfare is maximized. “Market failure” arises when imperfections cause outcomes that fall short of the ideal. If we were to do the same thing in politics, we would begin with a model in which the political system produced ideal outcomes and then consider factors that take us away from the ideal.

The model “in which consumer welfare is maximized” — perfect competition — is unattainable in most of the real world, given constant shifts in tastes, preferences, technologies, the availability of factors of production. “Market failure” is nothing more than a label that a left-wing economist or politician pins out market a outcome of which he or his constituents (e.g., labor unions) happen to disapprove. (The long version of my case against “market failure” is here.)

Goodman continues:

[W]hereas in economics, “market failure” is considered an exception to the norm, in politics, “government failure” is the norm. In general, there is no model of political decision making that can reliably produce ideal outcomes.

I offer an example of a not-unusual kind of government failure: the scam perpetrated by Dennis Montgomery on intelligence officials, and the subsequent effort to cover up the gullibility of those officials. This is from “Hiding Details of Dubious Deal, U.S. Invokes National Security” (The New York Times, February 19, 2011):

For eight years, government officials turned to Dennis Montgomery, a California computer programmer, for eye-popping technology that he said could catch terrorists. Now, federal officials want nothing to do with him and are going to extraordinary lengths to ensure that his dealings with Washington stay secret.

The Justice Department, which in the last few months has gotten protective orders from two federal judges keeping details of the technology out of court, says it is guarding state secrets that would threaten national security if disclosed. But others involved in the case say that what the government is trying to avoid is public embarrassment over evidence that Mr. Montgomery bamboozled federal officials….

Interviews with more than two dozen current and former officials and business associates and a review of documents show that Mr. Montgomery and his associates received more than $20 million in government contracts by claiming that software he had developed could help stop Al Qaeda’s next attack on the United States. But the technology appears to have been a hoax, and a series of government agencies, including the Central Intelligence Agency and the Air Force, repeatedly missed the warning signs, the records and interviews show.

Mr. Montgomery’s former lawyer, Michael Flynn — who now describes Mr. Montgomery as a “con man” — says he believes that the administration has been shutting off scrutiny of Mr. Montgomery’s business for fear of revealing that the government has been duped.

“The Justice Department is trying to cover this up,” Mr. Flynn said. “If this unravels, all of the evidence, all of the phony terror alerts and all the embarrassment comes up publicly, too. The government knew this technology was bogus, but these guys got paid millions for it.”

Similar cases abound in the unrecorded history of government contracting. Most of them don’t involve outright scams, but they do involve vain, gullible, and pressured government officials who tolerate — and even encourage — shoddy work on the part of contractors. Why? Because (a) they have money to spend, (b) they’re expected to spend it, and (c) there’s no bottom-line accountability.

If the flaws in government programs and systems are detected, it’s usually years or decades after their inception, by which time the responsible individuals have gone on (usually) to better jobs or cushy pensions. And when the flaws are detected, the usual response of the politicians, officials, and bureaucrats with a stake in a program is to throw more money at it. It’s not their money, so what do they care?

I offer an illustrative example from my long-ago days as a defense analyst. There was an ambitious rear admiral (as they all are) whose “shop” in the Pentagon was responsible for preparing the Navy’s long-range plan for the development and acquisition of new ships, aircraft, long-range detections systems, missiles, and so on.

The admiral — like many of his contemporaries in the officer corps of the armed forces — had been indoctrinated in the RAND-McNamara tradition of quantitative analysis. Which is to say that most of them were either naïve or opportunistic believers in the reductionism of cost-effectiveness analysis.

By that time (this was in the early 1980s) I had long outgrown my own naïveté about the power of quantification. (An account of my conversion is here.) But I was still naïve about admirals and their motivations. Having been asked by the admiral for a simple, quantitative model with which he could compare the effectiveness of alternative future weapon systems, I marched into his office with a presentation that was meant to convince him of his folly. (This post contains the essence of my presentation.)

For my pains, I was banished forever from the admiral’s presence and given a new assignment. (I was working for a non-profit advisory organization with fixed funding, so my employment wasn’t at stake.) The admiral wanted to know how to do what he had made up his mind to do, not why he had chosen to do something that couldn’t be done except by committing intellectual fraud.

Multiply this kind of government-contractor relationship by a million, throw in the usual kind of contractor who is willing to sell the client what the client wants — feasible or not — and you have a general picture of the kind of failure that pervades government contracting. Adapt that picture to inter-governmental relationships, where the primary job of each bureaucracy (and its political patrons) is to preserve its funding, without regard for the (questionable) value of its services to taxpayers, and you have a general picture of what drives government spending.

In sum, what drives government spending is not the welfare of the American public. It is cupidity, ego, power-lust, ignorance, stupidity, and — above all — lack of real accountability. Private enterprises pay for their mistakes because, in the end, they are held accountable by consumers. Governments, by contrast, hold consumers accountable (as taxpayers).

Perhaps — just perhaps — the era of governmental non-accountability is coming to an end. We shall see.

Evolution, Human Nature, and “Natural Rights”

This post is so long that I have put the main text below the fold. The following annotated outline may tempt you to read on or prompt you to move along:

I. Why This Post: Background and Issues

Do humans have natural ends that have arisen through evolution? If so, does this somehow imply the necessity of negative “natural rights”?

II. Natural Teleology –> Negative “Natural Rights”?

A. Evolution as God-Substitute

A supernatural explanation of “natural rights” will not do for skeptics and atheists, who find that such rights inhere in humans as products of evolution, and nothing more. Pardon a momentary lapse into cynicism, but this strikes me as a way of taking God out of the picture while preserving the “inalienable rights” of Locke and Jefferson.

B. Teleology as Tautology

Survival is the ultimate end of animate beings. Everything that survives has characteristics that helped to ensure its survival. What could be more obvious or more trivial?

C. Whence the Tautology?

Evolutionary teleology boils down to “what happened as a result of breeding, random mutation, geophysical processes, and survival of the fittest and/or luckiest, as the case may be.” The term “natural selection” is inappropriate because — unless there is such a thing as Intelligent Design — no one (or no thing) is selecting anything.

III. Persisting in the Search for Negative “Natural Rights” in Human Nature

A. Pro: Evolution Breeds Morality

“Darwin saw that social animals are naturally inclined to cooperate with one another for mutual benefit. Human social and moral order arises as an extension of this natural tendency to social cooperation based on kinship, mutuality, and reciprocity. Modern Darwinian study of the evolution of cooperation shows that such cooperation is a positive-sum game…”

B. Con: Human Nature Is Too Complex and Contradictory to Support Biologically Determined Rights

The account of human nature drawn from evolutionary psychology suggests that there is much in human nature which conflicts with negative rights in general (whether or not they are “natural”). And who needs a treatise on evolutionary psychology to understand the depth of that conflict? All it takes is a quick perusal of a newspaper, a few minutes of exposure to broadcast news, or a drive on a crowded interstate highway.

IV. A Truly Natural Explanation of Negative Rights

A. The Explanation

The Golden Rule represents a social compromise that reconciles the various natural imperatives of human behavior (envy, combativeness, meddlesomeness, etc.). To the extent that negative rights prevail, it is as part and parcel of the “bargain” that is embedded in the Golden Rule; that is, they are honored not because of their innateness in humans but because of their beneficial consequences.

B. The Role of Government

Government can provide “protective cover” for persons who try to live by the Golden Rule. This is especially important in a large and diverse political entity because the Golden Rule — as a code of self-governance — is possible only for a group of about 25 to 150 persons.

V. What Difference Does It Make?

The assertion that there are “natural rights” (“inalienable rights”) makes for resounding rhetoric, but (a) it is often misused in the service of positive rights and (b) it makes no practical difference in a world where power routinely accrues to those who make the something-for-nothing promises of positive rights.

See especially:

Negative Rights

Negative Rights, Social Norms, and the Constitution

Rights, Liberty, the Golden Rule, and the Legitimate State

“Natural Rights” and Consequentialism

More about Consequentialism

Positivism, “Natural Rights,” and Libertarianism

What Are “Natural Rights”?

The Golden Rule and the State

* * *

Continue reading “Evolution, Human Nature, and “Natural Rights””

Wrong Again

Steven Landsburg, who is supposedly a “hardcore libertarian,” is on the verge of surpassing Bryan Caplan as the most wrong-headed libertarian economist on my RSS reading list. Landsburg’s upside-down view of the world has led me to issue the following posts:

- “Landsburg Is Half-Right“

- “Rawls Meets Bentham“

- “The Case of the Purblind Economist“

- “Take Landsburg’s Money“

Now comes Landsburg with yet another tour through the land of tortured logic: “Another Rationality Test.” There, Landsburg sets out the following problem:

Suppose you’ve somehow found yourself in a game of Russian Roulette. Russian roulette is not, perhaps, the most rational of games to be playing in the first place, so let’s suppose you’ve been forced to play.

Question 1: At the moment, there are two bullets in the six-shooter pointed at your head. How much would you pay to remove both bullets and play with an empty chamber?

Question 2: At the moment, there are four bullets in the six-shooter. How much would you pay to remove one of them and play with a half-full chamber?

In case it’s hard for you to come up with specific numbers, let’s ask a simpler question:

The Big Question: Which would you pay more for — the right to remove two bullets out of two, or the right to remove one bullet out of four?

The question is to be answered on the assumption that you have no heirs you care about, so money has no value to you after you’re dead.

If you think the right answer is to pay more for the right to remove two bullets out of two, you’re wrong, according to Landsburg. Why? Well, Landsburg — with a train of “logic” that reminds me of Lou Costello’s “proof” that 7 x 13 = 28 — “proves” that removing two of four bullets has the same value as removing two of two bullets. Here’s how Landsburg does it:

[T]hink about four questions:

Question A: You’re playing with a six-shooter that contains two bullets. How much would you pay to remove them both? (This is the same as Question 1.)

Question B: You’re playing with a three-shooter that contains one bullet. How much would you pay to remove that bullet?

Question C: There’s a 50% chance you’ll be summarily executed and a 50% chance you’ll be forced to play Russian roulette with a three-shooter containing one bullet. How much would you pay to remove that bullet?

Question D: You’re playing with a six-shooter that contains four bullets. How much would you pay to remove one of them? (This is the same as Question 2.)

Now here comes the argument:

- In Questions A and B you are facing a 1/3 chance of death, and in each case you are offered the opportunity to escape that chance of death completely. Therefore they’re really the same question and they should have the same answer.

- In Question C, half the time you’re dead anyway. The other half the time you’re right back in Question B. So surely questions C and B should have the same answer.

- In Question D, there are three bullets that aren’t for sale. 50% of the time, one of those bullets will come up and you’re dead. The other 50% of the time, you’re playing Russian roulette with the three remaining chambers, one of which contains a bullet. Therefore Question D is exactly like Question C, and these questions should have the same answer.

Okay, then. If Questions A and B should have the same answer, and Questions B and C should have the same answer, and Questions C and D should have the same answer — then surely Questions A and D should have the same answer! But these, of course, are exactly the two questions we started with.

In case the trick isn’t obvious on first reading — and it wasn’t to me — here’s what Landsburg does.

He starts by positing a situation in which removing two of two bullets (Question A/Question 1) and removing one of one bullet (Question B) have the same value, and therefore should be worth the same amount to the hypothetical, involuntary player of Russian Roulette. Why should they have the same value? Because, given the player’s unstated but implicit objective — which is to survive Russian Roulette, and nothing else — he stands to improve his chance of surviving by 1/3 in both cases. Probabilistically, removing two of two bullets from a six-chamber gun is the same as removing one of one bullet from a three-chamber gun. In both instances, the chance of being shot goes from one-third to zero.

The point of the preceding exercise isn’t to get the reader to think about probabilities; it’s to get the reader (a) to assume that Landsburg’s “proof” is on the up-and-up, while (b) planting the idea that removing one of one bullets from three chambers is just as good as removing two of two bullets from six chambers. The reader is being set up to fall for a real whopper, to which I’ll come.

The next step (Question C) is to juxtapose the threat of dying by three-shooter with an irrelevant but equally probable threat. The 50% probability of summary execution is irrelevant, in the context of the problem at hand, because there’s nothing the player can do about it. What the player can do is to influence his probability of surviving Russian Roulette, which increases by one-third if he buys the single bullet that’s in the three-shooter.

The point of the preceding exercise is to reinforce further the reader’s confidence in Landsburg’s “proof,” while planting the idea that it’s legitimate to ignore a 50% threat of certain extinction. I use the word “confidence” because the setup of this “proof” is like the setup of a confidence game. The reader, like the victim of a con game, is now ripe for plucking.

Landsburg’s answer to Question D (Question 2) does the trick. It parallels Question C, but it doesn’t have the same import with respect to the player’s objective: surviving a game of Russian Roulette. Landsburg waves away 50% of the threat to the player’s existence (the three bullets that the player can’t buy), even though the three bullets (one of which may come up 50% of the time) are part of the game of Russian Roulette, unlike the summary execution of Question C. Landsburg, having dismissed the threat posed by the three bullets as somehow irrelevant, then focuses on the remaining bullet. Because this bullet can be in one of three chambers (the three not occupied by the other bullets), it seems that the player can increase by one-third his chance of surviving Russian Roulette if he buys one bullet. Thus, by Landburg’s “logic,” buying one of four bullets has the same value to the player as buying two of two bullets.

If you swallow that one, I’d like to sell you a bridge.

The fact that the player can’t buy three of the four bullets posited in Question D/Question 2, has no bearing on the probability that he survives Russian Roulette, which is his objective. With four bullets in the gun, his chance of survival is one-third. If he pays to have one bullet removed, the gun still has three bullets in it. Thus his chance of survival increases by one-sixth (3/6 [1/2] – 2/6 [1/3] = 1/6). Clearly, the value of removing one of four bullets isn’t the same as the value of removing two of two bullets, which increases his chance of survival by 1/3.

If you’re not convinced, let’s return to the original problem and restate it in a way that doesn’t distort the essential question: If the player’s objective is to survive a game of Russian Roulette, would he pay more for a six-gun with no bullets in it (Question 1) or a six-gun with three bullets in it (Question 2)? If you say that he’d pay the same amount for either gun, your name is Steven Landsburg.

Intelligence, Personality, Politics, and Happiness

Web pages that link to this post usually consist of a discussion thread whose participants’ views of the post vary from “I told you so” to “that doesn’t square with me/my experience” or “MBTI is all wet because…”. Those who take the former position tend to be persons of above-average intelligence whose MBTI types correlate well with high intelligence. Those who take the latter two positions tend to be persons who are defensive about their personality types, which do not correlate well with high intelligence. Such persons should take a deep breath and remember that high intelligence (of the abstract-reasoning-book-learning kind measured by IQ tests) is widely distributed throughout the population. As I say below, ” I am not claiming that a small subset of MBTI types accounts for all high-IQ persons, nor am I claiming that a small subset of MBTI types is populated entirely by high-IQ persons.” All I am saying is that the bits of evidence which I have compiled suggest that high intelligence is more likely — but far from exclusively — to be found among persons with certain MBTI types.

The correlations between intelligence, political leanings, and happiness are admittedly more tenuous. But they are plausible.

Leftists who proclaim themselves to be more intelligent than persons of the right do so, in my observation, as a way of reassuring themselves of the superiority of their views. They have no legitimate basis for claiming that the ranks of highly intelligent persons are dominated by the left. Leftist “intellectuals” in academia, journalism, the “arts”, and other traditional haunts of leftism are prominent because they are vocal. But they comprise a small minority of the population and should not be mistaken for typical leftists, who seem mainly to populate the ranks of the civil service, labor unions, public-school “educators”, and the unemployed. (It is worth noting that public-school teachers, on the whole, are notoriously dumber than most other college graduates.)

Again, I am talking about general relationships, to which there are many exceptions. If you happen to be an exception, don’t take this post personally. You’re probably an exceptional person.

IQ AND PERSONALITY

Some years ago I found statistics about the personality traits of high-IQ persons (those who are in the top 2 percent of the population).* The statistics pertain to a widely used personality test called the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), which I have taken twice. In the MBTI there are four pairs of complementary personality traits, called preferences: Extraverted/Introverted, Sensing/iNtuitive, Thinking/Feeling, and Judging/Perceiving. Thus, there are 16 possible personality types in the MBTI: ESTJ, ENTJ, ESFJ, ESFP, and so on. (For an introduction to MBTI, summaries of types, criticisms of MBTI, and links to other sources, see this article at Wikipedia. A straightforward description of the theory of MBTI and the personality traits can be found here. Detailed descriptions of the 16 types are given here.)

In summary, here is what the statistics indicate about the correlation between personality traits and IQ:

- Other personality traits being the same, an iNtuitive person (one who grasps patterns and seeks possibilities) is 25 times more likely to have a high IQ than a Sensing person (one who focuses on sensory details and the here-and-now).

- Again, other traits being the same, an Introverted person is 2.6 times more likely to have a high IQ than one who is Extraverted; a Thinking (logic-oriented) person is 4.5 times more likely to have a high IQ than a Feeling (people-oriented) person; and a Judging person (one who seeks closure) is 1.6 times as likely to have a high IQ than a Perceiving person (one who likes to keep his options open).

- Moreover, if you encounter an INTJ, there is a 22% probability that his IQ places him in the top 2 percent of the population. (Disclosure: I am an INTJ.) Next are INTP, at 14%; ENTJ, 8%; ENTP, 5%; and INFJ, 5%. (The next highest type is the INFP at 3%.) The five types (INTJ, INTP, ENTJ, ENTP, and INFJ) account for 78% of the high-IQ population but only 15% of the total population.**

- Four of the five most-intelligent types are NTs, as one would expect, given the probabilities cited above. Those same probabilities lead to the dominance of INTJs and INTPs, which account for 49% of the Mensa membership but only 5% of the general population.**

- Persons with the S preference bring up the rear, when it comes to taking IQ tests.**

A person who read an earlier version of this post claims that “one would expect to see the whole spectrum of intelligences within each personality type.” Well, one does see just that, but high intelligence is skewed toward the five types listed above. I am not claiming that a small subset of MBTI types accounts for all high-IQ persons, nor am I claiming that a small subset of MBTI types is populated entirely by high-IQ persons.

I acknowledge reservations about MBTI, such as those discussed in the Wikipedia article. An inherent shortcoming of psychological tests (as opposed to intelligence tests) is that they rely on subjective responses (e.g., my favorite color might be black today and blue tomorrow). But I do not accept this criticism:

[S]ome researchers expected that scores would show a bimodal distribution with peaks near the ends of the scales, but found that scores on the individual subscales were actually distributed in a centrally peaked manner similar to a normal distribution. A cut-off exists at the center of the subscale such that a score on one side is classified as one type, and a score on the other side as the opposite type. This fails to support the concept of type: the norm is for people to lie near the middle of the subscale.

Why was it expected that scores on a subscale (E/I, S/N, T/F, J/P) would show a bimodal distribution? How often does one encounter a person who is at the extreme end of any subscale? Not often, I wager, except in places where such extremes are likely to be clustered (e.g., Extraverts in politics, Introverts in monasteries). The cut-off at the center of each subscale is arbitrary; it simply affords a shorthand characterization of a person’s dominant traits. But anyone who takes an MBTI (or equivalent instrument) is given his scores on each of the subscales, so that he knows the strength (or weakness) of his tendencies.

Regarding other points of criticism: It is possible, of course, that a person who is familiar with MBTI tends to see in others the characteristics of their known MBTI types (i.e., confirmation bias). But has that tendency been confirmed by rigorous testing? Such testing would examine the contrary case, that is, the ability of a person to predict the type of a person whom he knows well (e.g., a co-worker or relative).

The supposed vagueness of the descriptions of the 16 types arises from the complexity of human personality; but there are differences among the descriptions, just as there are differences among individuals. According to a footnote to an earlier version of the Wikipedia article about MBTI, half of the persons who take the MBTI are able to guess their types before taking it. Does that invalidate MBTI or does it point to a more likely phenomenon, namely, that introspection is a personality-related trait, one that is more common among Introverts than Extraverts? A good MBTI instrument cuts through self-deception and self-flattery by asking the same set of questions in many different ways, and in ways that do not make any particular answer seem like the “right” one.

IQ AND POLITICS

It is hard to find clear, concise analyses of the relationship between IQ and political leanings. I offer the following in evidence that very high-IQ individuals lean strongly toward libertarian positions.

The Triple Nine Society (TNS) limits its membership to persons with IQs in the top 0.1% of the population. In an undated survey (probably conducted in 2000, given the questions about the perceived intelligence of certain presidential candidates), members of TNS gave their views on several topics (in addition to speculating about the candidates’ intelligence): subsidies, taxation, civil regulation, business regulation, health care, regulation of genetic engineering, data privacy, death penalty, and use of military force.

The results speak for themselves. Those members of TNS who took the survey clearly have strong (if not unanimous) libertarian leanings.

THE RIGHT IS SMARTER THAN THE LEFT

I count libertarians as part of the right because libertarians’ anti-statist views are aligned with the views of the traditional (small-government) conservatives who are usually Republicans. Having said that, the results reported in “IQ and Politics” lead me to suspect that the right is smarter than the left, left-wing propaganda to the contrary notwithstanding. There is additional evidence for my view.

A site called Personality Page offers some data about personality type and political affiliation. The sample is not representative of the population as a whole; the average age of respondents is 25, and introverted personalities are over-represented (as you might expect for a test that is apparently self-administered through a website). On the other hand, the results are probably unbiased with respect to intelligence because the data about personality type were not collected as part of a study that attempts to relate political views and intelligence, and there is nothing on the site to indicate a left-wing bias. (Psychologists, who tend toward leftism, have a knack for making conservatives look bad, as discussed here, here, and here. If there is a strong association between political views and intelligence, it is found among so-called intellectuals, where the herd mentality reigns supreme.)

The data provided by Personality Page are based on the responses of 1,222 individuals who took a 60-question personality test that determined their MBTI types (see “IQ and Personality”). The test takers were asked to state their political preferences, given these choices: Democrat, Republican, middle of the road, liberal, conservative, libertarian, not political, and other. Political self-labelling is an exercise in subjectivity. Nevertheless, individuals who call themselves Democrats or liberals (the left) are almost certainly distinct, politically, from individuals who call themselves Republicans, conservatives, or libertarians (the right).

Now, to the money question: Given the distribution of personality types on the left and right, which distribution is more likely to produce members of Mensa? The answer: Those who self-identify as persons of the right are 15 percent more likely to qualify for membership in Mensa than those who self-identify as persons of the left. This result is plausible because it is consistent with the pronounced anti-government tendencies of the very-high-IQ members of the Triple Nine Society (see “IQ and Politics”).

REPUBLICANS (AND LIBERTARIANS) ARE HAPPIER THAN DEMOCRATS

That statement follows from research by the Pew Research Center (“Are We Happy Yet?”, February 13, 2006) and Gallup (“Republicans Report Much Better Health Than Others”, November 30, 2007).

Pew reports:

Some 45% of all Republicans report being very happy, compared with just 30% of Democrats and 29% of independents. This finding has also been around a long time; Republicans have been happier than Democrats every year since the General Social Survey began taking its measurements in 1972….

Of course, there’s a more obvious explanation for the Republicans’ happiness edge. Republicans tend to have more money than Democrats, and — as we’ve already discovered — people who have more money tend to be happier.

But even this explanation only goes so far. If one controls for household income, Republicans still hold a significant edge: that is, poor Republicans are happier than poor Democrats; middle-income Republicans are happier than middle-income Democrats, and rich Republicans are happier than rich Democrats.

Gallup adds this:

Republicans are significantly more likely to report excellent mental health than are independents or Democrats among those making less than $50,000 a year, and among those making at least $50,000 a year. Republicans are also more likely than independents and Democrats to report excellent mental health within all four categories of educational attainment.

There is a lot more in both sources. Read them for yourself.

Why would Republicans be happier than Democrats? Here’s my thought, Republicans tend to be conservative or libertarian (at least with respect to minimizing government’s role in economic affairs). Consider Thomas Sowell’s A Conflict of Visions:

He posits two opposing visions: the unconstrained vision (I would call it the idealistic vision) and the constrained vision (which I would call the realistic vision). As Sowell explains, at the end of chapter 2:

The dichotomy between constrained and unconstrained visions is based on whether or not inherent limitations of man are among the key elements included in each vision…. These different ways of conceiving man and the world lead not merely to different conclusions but to sharply divergent, often diametrically opposed, conclusions on issues ranging from justice to war.

Idealists (“liberals”) are bound to be less happy than realists (conservatives and libertarians) because idealists’ expectations about human accomplishments (aided by government) are higher than those of realists, and so idealists are doomed to disappointment.

All of this is consistent with findings reported by law professor James Lindgren:

[C]ompared to anti-redistributionists, strong redistributionists have about two to three times higher odds of reporting that in the prior seven days they were angry, mad at someone, outraged, sad, lonely, and had trouble shaking the blues. Similarly, anti-redistributionists had about two to four times higher odds of reporting being happy or at ease. Not only do redistributionists report more anger, but they report that their anger lasts longer. When asked about the last time they were angry, strong redistributionists were more than twice as likely as strong opponents of leveling to admit that they responded to their anger by plotting revenge. Last, both redistributionists and anti-capitalists expressed lower overall happiness, less happy marriages, and lower satisfaction with their financial situations and with their jobs or housework. [Northwestern Law and Economics Research Paper 06-29, “What Drives Views on Government Redistribution and Anti-Capitalism: Envy or a Desire for Social Dominance?”, March 15, 2011]

THE BOTTOM LINE

If you are very intelligent — with an IQ that puts you in the top 2 percent of the population — you are most likely to be an INTJ, INTP, ENTJ, ENTP, or INFJ, in that order. Your politics will lean heavily toward libertarianism or small-government conservatism. You probably vote Republican most of the time because, even if you are not a card-carrying Republican, you are a staunch anti-Democrat. And you are a happy person because your expectations are not constantly defeated by reality.

Related reading (listed chronologically):

Jeff Allen, “Conservatives: The Smartest (and Happiest) People in the Room“, Barbed Wire, February 20, 2014

James Thompson, “Election Special: Are Republicans Smarter than Democrats?”, The Unz Review, November 3, 2016

Dennis Prager, “Liberals and Conservatives are Unhappy for Different Reasons“, Townhall, February 13, 2018

John J. Ray, “Leftists Are Born Unhappy“, Dissecting Leftism, February 14, 2018

Related posts:

Intelligence and Intuition

Intelligence As a Dirty Word

Footnotes:

* I apologize for not having documented the source of the statistics that I cite here. I dimly recall finding them on or via the website of American Mensa, but I am not certain of that. And I can no longer find the source by searching the web. I did transcribe the statistics to a spreadsheet, which I still have. So, the numbers are real, even if their source is now lost to me.

** Estimates of the distribution of MBTI types in the U.S. population are given in two tables on page 4 of “Estimated Frequencies of the Types in the United States Population”, published by the Center for Applications of Psychological Type. One table gives estimates of the distribution of the population by preference (E, I, N, S, etc.). The other table give estimates of the distribution of the population among all 16 MBTI types. The statistics for members of Mensa were broken down by preferences, not by types; therefore I had to use the values for preferences to estimate the frequencies of the 16 types among members of Mensa. For consistency, I used the distribution of the preferences among the U.S. population to estimate the frequencies of the 16 types among the population, rather than use the frequencies provided for each type. For example, the fraction of the population that is INTJ comes to 0.029 (2.9 percent) when the values for I (0.507), N (0.267), T (0.402), and J (0.541) are multiplied. But the detailed table has INTJs as 2.1 percent of the population. In sum, there are discrepancies between the computed and given values of the 16 types in the population. The most striking discrepancy is for the INFJ type. When estimated from the frequencies of the four preferences, INFJs are 4.4 percent of the population; the table of values for all 16 types gives the percentage of INFJs as 1.5 percent.

Using the distribution given for the 16 types leads to somewhat different results:

- There is a 31-percent probability that an INTJ’s IQ places him in the top 2 percent of the population. Next are INFJ, at 14 percent; ENTJ, 13 percent; and INTP, 10 percent. (The next highest type is the ENTP at 4 percent.) The four types (INTJ, INFJ, ENTJ, AND INTP) account for 72 percent of the high-IQ population but only 9 percent of the total population. The top five types (including ENTPs) account for 78 percent of the high-IQ population but only 12 percent of the total population.

- Four of the five most-intelligent types are NTs, as one would expect, given the probabilities cited earlier. But, in terms of the likelihood of having an IQ, this method moves INFJs into second place, a percentage point ahead of ENTJs.

- In any event, the same five types dominate, and all five types have a preference for iNtuitive thinking.

- As before, persons with the S preference generally lag their peers when it comes to IQ tests.

Take Landsburg’s Money, Revised

This is to let you know that if you’ve read “Take Landsburg’s Money,” you should take another look at it. I’ve added some material.

That’s all I’ll say here. Go there and see for yourself.

Take Landsburg’s Money

REVISED 01/01/11 and 01/02/11, with the addition of new material (clearly indicated).

Economist-mathematician Steven Landsburg recently offered a problem and later posted a purported solution to it. Landsburg is so confident that his solution is the correct one that he has offered to bet significant sums of money that it’s the correct one. And, as of this morning, Landsburg still insists that he has the right answer.

The problem is one (among many) that Google has posed to candidates for employment. Landsburg states it as follows:

There’s a certain country where everybody wants to have a son. Therefore each couple keeps having children until they have a boy; then they stop. What fraction of the population is female? [The actual wording of the question, according to this source, is slightly different, but Landsburg’s paraphrase is faithful to the meaning.]

He adds:

Well, of course, you can’t know for sure, because, by some extraordinary coincidence, the last 100,000 families in a row might have gotten boys on the first try. But in expectation, what fraction of the population is female? In other words, if there were many such countries, what fraction would you expect to observe on average?

I first heard this problem decades ago, and so, perhaps, did you. It comes up in job interviews at places like Google. The answer they expect is simple, definitive and wrong.

And no, it’s not wrong because of small discrepancies between the number of male and female births, or because of anything else that’s extraneous to the spirit of the problem. It’s just really wrong. The correct answer, unlike the expected one, is not simple.

According to Landsburg, the “obvious” — but wrong — answer is that one-half of the children are boys and one-half of the children are girls. Landsburg rejects the “obvious” answer, with this explanation:

I’ll start with the case where there’s just one couple. Here are some possible family configurations, with their probabilities:

From this we see that the expected number of boys is

which adds to 1. And the expected number of girls is

which also adds to 1. Sure enough, the expected number of girls is equal to the expected number of boys.

But the expected fraction of girls is

which adds to 1-log(2), or about 30.6%.

For a population of k families, a similar calculation gives an answer of approximately (but not exactly) (1/2) – (1/4k), which, when k is large, is approximately (but not exactly) 1/2.

Elsewhere, Landsburg offers to make bets with readers who disagree with his analysis, and to settle matters through the use of simulation. But (a) I’m not interested in betting and (b) I prefer to treat the problem as one of mathematical expectation, which Landsburg also (rightly) prefers. He suggests the use of simulation only as a way of convincing some skeptics of the correctness of his analysis.

Interestingly, Landsburg’s “solution” — an expected girl fraction of 0.3068 for one family and, presumably, not quite 0.5 for the entire country — is at odds another person’s solution (girl fraction ~0.61),to which Landsburg points favorably. This discrepancy suggests some confusion on Landsburg’s part, which is evident in his depiction of the possible configurations of a single family (the children in the family, actually). He takes a special case — which omits the possibility of a first-born girl. He then generalizes from that special case.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

This section added 01/01/11 and revised slightly for clarity on 01/02/11:

What I took for an omission on Landburg’s part (the possibility of a first-born girl), isn’t an omission — in Landsburg’s view. His estimate of the girl fraction for a family is for a completed family (his term, not mine). Thus the configurations B, GB, GGB, GGGB, etc.

But there’s no such thing (in the context of a single family) as a completed family. (In a large number of families, there may be a completed families, but every one of them will be matched by an equal number of uncompleted families. More about that below.) No particular couple ever has a boy with an a priori probability = 1, which is what Landsburg implies (inadvertently, I’m sure) when he focuses on B, GB, GGB, GGGB, etc., where the B in each case signifies the end of a possible sequence of children.

On the contrary, if PB = 1/2 at all times (and not 1 at arbitrary times) every boy must be accompanied by a girl, with equal probability. (Alternatively, shades of Schrödinger’s cat, the probability wave collapses to PB =1 when Landsburg decides that enough kids are enough.) Here’s a schematic depiction of what happens when Landsburg doesn’t play with the probabilities:

On the left side of the vertical line, the probable first-born boy, being only probable, is followed by a probable boy or girl, and so on. On the right side, the probable first-born girl is followed by a probable boy or girl, and so on. On both sides, the possible configurations take the form Child 1, Child 1 + Child 2, Child 1 + Child 2 + Child 3, etc.

Landburg, in effect, has restricted his view of the possible configurations to the left side of the diagram.With the whole diagram in view, it’s obvious that the fraction of girls in each stage, and through each stage, is always 1/2.

End of section. Original post continues below the line.

________________________________________________________________________________________

To analyze the problem correctly it’s helpful to spell out all of its conditions and (sometimes implicit) assumptions:

- The basic rule — couples have children until a boy is born, but not after that — means that no couple in country X will have more than 1 boy, but the number of girls is limited only to the number of children that a couple generates before having a boy.

- A couple can generate children endlessly, if necessary. That is to say, there’s no limit on the number of children a couple may produce and no limit on the time in which they may produce them.

- The probability that any given birth will result in a boy (B) or girl (G) is 1/2 for each; that is PB = PG = 1/2. (The actual fractions, I gather, are about 0.52 boys and 0.48 girls per birth.) These probabilities never vary, and are always the same for every couple.

- Given the open-ended nature of the problem, it’s possible that some couples will have an infinite number of children without producing a boy. But, given the preceding statement, the first-born of half the couples will be a boy; those couples will have no more children.

- The situation begins at a finite time (t = 0) and only those children born to the couples in country X after t = 0 are counted.

- Children are born at a uniform rate, so that all the first-borns are born at t = 1; all the second-borns at t = 2; and so on. (This assumption and the preceding one don’t affect the results, but they allow for a simple illustration of the problem.)

- In computing the fraction of boys and girls in the population, it’s assumed that there are no abortions or miscarriages, and that no children die at birth or later.

Perhaps the solution to the problem will be easier to see if the problem is recast, so that B = blue ball, G = green ball, and “couple” becomes “player”:

- There’s a large but finite number of urns. Each is full of colored balls. Half of them are blue (B); half of them are green (G).

- Positioned at each urn is a player whose job it is to make a blind draw of one ball from his urn at a regular interval (say, 1 minute). Each ball is kept by the player who draws it.

- As each ball is drawn, the keeper of the urn from which it is drawn replaces it with a new ball of the same color, and mixes the balls thoroughly to ensure the randomness of the next draw.

- When a player draws a B, he keeps it but doesn’t draw any more balls.

- When a player draws a G, he keeps it and draws another ball (from the replenished urn) a minute later. This continues until the player draws a B.

- It’s possible that some players will never draw a B.

All of the other assumptions stated earlier apply in this case (e.g., PB = PG = 1/2, PB and PG never vary and are always the same for every player).

Consider the following illustration of the results of the first four rounds of play:

| Illustration of the General Case ( with 10,000 urns) | ||||

| B | G | Total | G fraction | |

| Minute 1 | 5,000 | 5,000 | 10,000 | 1/2 |

| Total | 5,000 | 5,000 | 10,000 | 1/2 |

| Minute 2 | 2,500 | 2,500 | 5,000 | 1/2 |

| Total | 7,500 | 7,500 | 15,000 | 1/2 |

| Minute 3 | 1,250 | 1,250 | 2,500 | 1/2 |

| Total | 8,750 | 8,750 | 17,500 | 1/2 |

| Minute 4 | 625 | 625 | 1,250 | 1/2 |

| Total | 9,375 | 9,375 | 18,750 | 1/2 |

The 5,000 players who draw a B at minute 1 stop drawing, but they keep the Bs that they draw. The 5,000 players who draw a G at minute 1 keep their Gs and make another draw at minute 2. That draw results in the selection of 2,500 Bs and 2,500 Gs, which are kept by the players who draw them. The 2,500 players who draw a G at minute 2 make another draw at minute 3, which results in the selection of 1,250 Bs and 1,250 Gs, and so on.

At this point, it’s important to note that the stopping rule has no effect on the fractions of B and G drawn in any round of play. Given that PB and PG are always the same for each and every player, as stated in the list of assumptions, it doesn’t matter whether or when players drop out of the game or join the game, or under what conditions they drop out or join, as long as PB = PG = 1/2, always and for every player. Given those conditions — which are central (implicit) assumptions of the original Google problem — every round of play, from the first one onward, results in equal (expected) numbers of B and G.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

This section added and revised 01/02/11.

In the example of 10,000 players with 10,000 urns, the number of players at minute 5 would be an odd number, and the number of players at minute 6 and beyond wouldn’t be an integer. But the example is about expected values (as it should be), so the lack of an even, whole number of players after minute 4 wouldn’t affect the import of the example.

To show what happens in the “end game,” I turn to a slightly different example, which begins with a number of players such that there can be exactly two left in the penultimate round, after all others have drawn a B. What happens when one of the two players draws a B while the other draws a G? Good question. First of all, the draws to and including that round will have resulted in an equal number of B and G. What happens next is a matter of pure chance. The final player — the one whose penultimate draw is a G — has an equal chance of drawing a G or a B on his next and final draw. The chance of drawing a B doesn’t suddenly jump to 1, nor does the chance of drawing a G suddenly jump to 1. The game could end there, with equal numbers of B and G having been drawn and a final draw to be made with PB = PG = 1/2. But there’s no reason to expect that the final draw will be a B, to the exclusion of a G, or vice versa.

Schematically:

(The Gs drawn by players 8191 and 8192 in rounds 1-11 would have been matched, in each round, by other players who draw Bs in those rounds. Players 8191 and 8192, in this example, would be the only players left for round 12.)

End of section. Original post continues below the line.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Mathematically, the expected numbers of B and G (EB and EG) drawn by a single player are as follows:

EB = (1)(1/2) + (1/2)(1/2) + (1/4)(1/2) + (1/8)(1/2) + … = 1

EG = (1)(1/2) + (1/2)(1/2) + (1/4)(1/2) + (1/8)(1/2) + … = 1

The expected fraction of G is:

EG/(EG + EB) = (1/2)(1/2) + (1/4)(1/2) + (1/8)(1/2) + … = 1/2,

which reduces to PG/(PG + PB) = 1/2

Given N players, the expected numbers of B and G are:

EB = (N)(1/2) + (N/2)(1/2) + (N/4)(1/2) + (N/8)(1/2) + … = N

EG = (N)(1/2) + (N/2)(1/2) + (N/4)(1/2) + (N/8)(1/2) + … = N

Again, given the “rules” of the game (i.e., of the original Google problem), the expected fraction of G is always 1/2, at every point in the game and in its expected (but never reached) outcome.

The stopping rule is a red herring, intended (I suspect) to draw attention from the essential fact that EB = EG, always and for everyone, no matter how many players (couples) there are or when and under what conditions they join or leave the game (start or stop having children).

* * *

To Prof. Landsburg, should he read this post:

If you don’t immediately spot a fatal flaw in my analysis, why not have some members of U of R’s stat department check it out? That seems to me to be the best way to settle the issue.

If you conclude that my analysis is correct (in the essentials, at least), you won’t owe me any money because we haven’t made a bet. (You couldn’t send me money, anyway, unless you are able to penetrate my anonymity.) Just acknowledge my contribution prominently in a post on your blog and add a link to my blog in your sidebar (perhaps under the heading “Unclassified Blogs”).

* * *

This isn’t the first time that Landsburg has attracted my attention:

Landsburg Is Half-Right

Rawls Meets Bentham

The Case of the Purblind Economist

Finding Order in Chaos

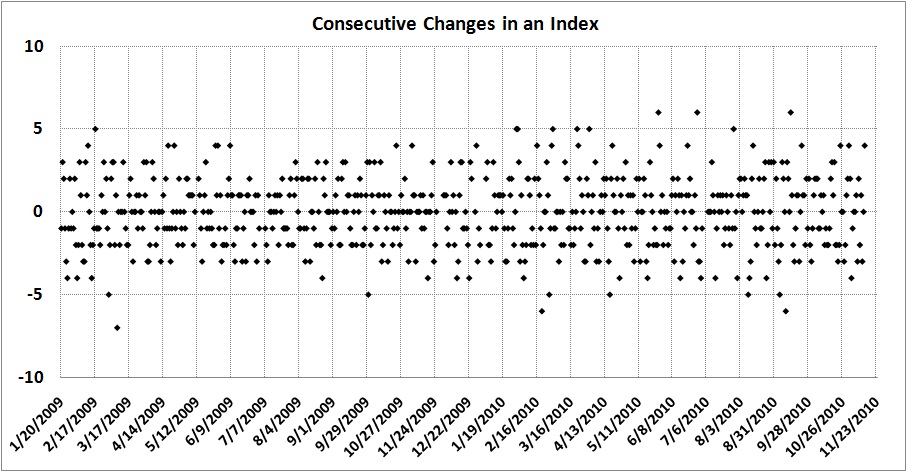

Here is an apparently random plot of daily changes in an index:

Can such randomness yield an orderly outcome? To find out, click “Read more of this post.”

Experts and the Economy

In “Socialist Calculation and the Turing Test,” I wrote about the

suggestion … that one can emulate the outcomes that would be produced by competitive markets — if not something “better” — by writing rules that, if followed, would mimic the behavior of competitive markets.The problem with that suggestion … is that someone outside the system must make the rules to be followed by those inside the system.

And that’s precisely where socialist planning and regulation always fail. At some point not very far down the road, the rules will not yield the outcomes that spontaneous behavior would yield. Why? Because better rules cannot emerge spontaneously from rule-driven behavior….

Where, for instance, is there room in the socialist or regulatory calculus for a rule that allows for unregulated monopoly? Yet such an “undesirable” phenomenon can yield desirable results by creating “exorbitant” profits that invite competition (sometimes from substitutes) and entice innovation. (By “unregulated” I don’t mean that a monopoly should be immune from laws against force and fraud, which must apply to all economic actors.)

I suppose exogenous rules are all right if you want economic outcomes that accord with those rules. But such rules aren’t all right if you want economic outcomes that actually reflect the wants of consumers….

Of course, the whole point of socialist planning is to produce outcomes that are desired by planners. Those desires reflect planners’ preferences, as influenced by their perceptions of the outcomes desired by certain subsets of the populace. The immediate result may be to make some of those subsets happier, but at a great cost to everyone else and, in the end, to the favored subsets as well. A hampered economy produces less for everyone.

Socialism — a.k.a. “liberalism” — is all about reliance on experts. As Don Boudreaux says,

modern “liberalism’s” ideas are about replacing an unimaginably large multitude of diverse and competing ideas – each one individually chosen, practiced, assessed, and modified in light of what F.A. Hayek called “the particular circumstances of time and place” – with a relatively paltry set of ‘Big Ideas’ that are politically selected, centrally imposed, and enforced not by the natural give, take, and compromise of the everyday interactions of millions of people but, rather, by guns wielded by those whose overriding ‘idea’ is among the most simple-minded and antediluvian notions in history, namely, that those with the power of the sword are anointed to lord it over the rest of us.

Megan McArdle puts it this way:

So we get [from central planning] what most interests wordsmiths: a succession of enormous plans (health care exchanges! privatize social security!), most of which fail….But all this makes me very skeptical of handing elites more power, particularly when they are given that power in order to reduce the autonomy of some other group. (And somehow, that usually is what it’s for–you haven’t seen much lobbying for better regulation of university professor quality, even though a bad idea is probably more dangerous than a bad apple.)

The Improbability of Us

An argument often used against the belief in a Creator who designed the universe runs like this:

The existence of humans is indeed improbable. The laws of nature that govern our existence are but one set out of infinitely many possible sets of laws of nature. Ad had they differed only slightly the universe would be a mere swirl of subatomic particles, free from medium-sized objects like rocks, trees and humans. And even given the actual laws of nature, evolutionary history would have taken different twists and turns and failed to deliver human beings. (Jamie Whyte, Bad Thoughts – A Guide to Clear Thinking, p. 125)

Embedded in that seemingly reasonable statement is an unwarranted — but critical — assumption: that there are infinitely many (or even a large number) of possible sets of laws of nature. But there is no way of knowing such a thing. There is only one observable universe, and one set of observable and (mostly*) consistent laws of nature within it. It is impossible for the human mind to conjure an alternative set of consistent natural laws that could, in fact, coexist in a possible universe. Any such conjuring would be mere speculation, not a falsifiable hypothesis.

Given that, it is impossible to deny that a grand design lies behind the universe. But it is also impossible to prove, by the methods of science, the existence of a grand design. The fact of the universe’s existence is, as I have called it, the greatest mystery.

Related posts:

Atheism, Religion, and Science

The Limits of Science

Three Perspectives on Life: A Parable

Beware of Irrational Atheism

The Creation Model

The Thing about Science

Evolution and Religion

Words of Caution for Scientific Dogmatists

Science, Evolution, Religion, and Liberty

The Legality of Teaching Intelligent Design

Science, Logic, and God

Capitalism, Liberty, and Christianity

Is “Nothing” Possible?

A Dissonant Vision

Debunking “Scientific Objectivity”

Science’s Anti-Scientific Bent

Science, Axioms, and Economics

The Big Bang and Atheism

The Universe . . . Four Possibilities

Einstein, Science, and God

Atheism, Religion, and Science Redux

Pascal’s Wager, Morality, and the State

Evolution as God?

The Greatest Mystery

What Is Truth?

__________

* The exception is quantum mechanics, the science of the sub-atomic world. Sub-atomic particles do not seem to behave according to the same physical laws that describe the actions of the visible universe; their behavior is discontinuous (“jumpy”) and described probabilistically, not by the kinds of continuous (“smooth”) mathematical formulae that apply to the macroscopic world.

Venus vs. Mars

Excerpts of a typically excellent post at Public Discourse, “Women, Abortion, and the Brain“:

Women’s brains are, of course, in many fundamental ways the same as men’s. Men and women think and reason in similar ways. But recent research shows that there are some significant differences in the brain and brain-related psychology of the two sexes. And a few of these differences can make a very large difference with regard to decision-making and its emotional consequences.

The part of the brain that processes emotion, generally called the limbic system, of women functions differently than that of men. Women experience emotions largely in relation to other people: what moves women most is relationships. Females are more personal and interpersonal than men. (Differences show up as early as a day after an infant’s birth: newborn baby girls look at faces relatively more than boys, who focus more on moving robotic figures.) There is wide consensus among scientists and researchers on this fundamental issue.

Recent research has also studied the ways in which males and females cope with stress. Whereas men’s behavior under stress is generally characterized by what is called “fight or flight,” women respond to stress by turning toward nurturing behavior, nicknamed “tend and befriend.”

Men’s and women’s brains also work differently in handling memory and memories. Men are more apt to recall facts of all kinds, on the one hand, and a global picture of events, on the other. By contrast, women remember people (for example, faces), details of all kinds, and emotion-laden narratives—and they may return to them obsessively.

I am only passingly familiar with the research that supports these observations, but they comport well with what I have seen in five decades as an adult. I offer, as just one of many possible examples, my daughter, who — untypically, for a woman — is much better with numbers than with words, and who has succeeded in the male-dominated field of investment banking. She is nevertheless strongly “feminine” in her emotions.

Radical feminists and egalitarians to the contrary, women aren’t just men with different anatomical features. There is a good case to be made for the injection of “feminine” traits into the worlds of business and politics. But there is no case to be made for enforced equality of pay or representation.

Individuals should be dealt with as individuals, not as “group members.” It is the levelers who are guilty of group bias, given their insistence that males and females are alike in their stock of mental and physical abilities — except that females are superior, of course.

Related posts:

Sexist Nonsense

Cornered by Gender?

The Population Mystery

Despite the doomsayers, past and present, the world’s population has grown and will grow:

Estimates for 10,000 B.C. through 1940 derived from U.S. Census Bureau, “Historical Estimates of World Population” (left column). Estimates for 1950 through 2050 derived from U.S. Census Bureau, “Total Midyear Population for the World: 1950-2050.” Intervals between years are irregular because of variations in the intervals in the Census tables.

Is it possible that the world’s population will reach an unsustainable level, after which it must shrink and/or plunge the world into abysmal poverty?

Donald Boudreaux, in a 2008 post, writes:

In his new book, Common Wealth, Jeffrey Sachs expresses his concern about population growth. Worried by a U.N. prediction that global population will rise to 9.2 billion by the year 2050, from 6.6 billion today, Sachs says (on page 23 of his new book) the following about these additional 2.6 billion persons:

I will argue at some length that this is too many people to absorb safely, especially since most of the population increase is going to occur in today’s poorest countries. We should be aiming….to stabilize the world’s population at 8 billion by midcentury.

Eight billion. I’m not sure where Sachs got that number. And, to be frank, I’m not curious about where he got it….

A … problem with Sachs’s eight-billion number is that, in calculating it, there is no way to predict how human creativity will alter the world during the next 42 years. It’s ludicrous to pretend that we can know now what, say, the average MPG will be for internal-combustion engines in 2050. Hell, we don’t even know if automobiles and lawnmowers and the like will still use such engines then.

Will another Norman Borlaug arise, between now and 2050, to spark another green revolution? Will someone invent a way to efficiently power automobiles with air? Will someone develop new and better techniques for defining and enforcing private property rights in ocean-going fish stocks so that the tragedy of the commons called “over-fishing” is eliminated? Will an enterprising entrepreneur invent a means for ordinary households to power their homes with mulch or autumn leaves or small fragments of fingernail clippings?

Think back 42 years to 1966. Who in that year imagined personal computers in nearly every home in America? The Internet? Digital cameras? Cell phones? Quality wines sold in screw-top bottles? Buying music with literally the click of a button (and not having to burn fossil fuels in driving to the record store). Aluminum cans that contain only a fraction of the metal that cans contained back then? The Kindle (that will reduce the number of trees cut down to enable people to read books)? Medical advances that make hip-replacements about as routine as getting cavities filled by the dentist? Microfiber?

There is no way — literally, no way — to know how technology and social institutions will change between now and 2050. Given this impossibility — and given the fact that we can nevertheless predict with confidence that technology will advance and that social institutions will change — to assert that “optimal” population in the year 2050 will be eight-billion persons is ludicrous in the extreme. It’s faux-science, and deserves only ridicule.

Here’s Bryan Caplan, writing today:

I finally got around to reading Matt Ridley’s The Rational Optimist. Highlights….

2. How non-renewable energy is more abundant than renewable energy:

The Atlantic Ocean is not infinite, but that does not mean you have to worry about bumping into Newfoundland if you row a dingy out of a harbour in Ireland. Some things are finite but vast; some things are infinitely renewable, but very limited. Non-renewable resources such as coal are sufficiently abundant to allow an expansion of both economic activity and population to the point where they can generate sustainable wealth for all the people of the planet without hitting a Malthusian ceiling, and can then hand the baton to some other form of energy.

3. The fallacy of pessimistic extrapolation:

[T]he pessimists are right when they say that, if the world continues as it is, it will end in disaster for humanity. If all transport depends on oil, and oil runs out, then transport will cease. If agriculture continues to depend on irrigation and aquifers are depleted, then starvation will ensue. But notice the conditional: if. The world will not continue as it is. That is the whole point of human progress, the whole message of cultural evolution, the whole import of dynamic change – and the whole thrust of this book….

5. Declining flu mortality is not dumb luck.

The modern way of life, with lots of travel but also rather more personal space, tends to encourage mild, casual-contact viruses that need their victims to be healthy enough to meet fresh targets fleetingly…

[W]hy then did H1N1 flu kill perhaps fifty million people in 1918? Ewald and others think the explanation lies in the trenches of the First World War. So many wounded soldiers, in such crowded conditions, provided a habitat ideally suited to more virulent behaviour by the virus: people could pass on the virus while dying….

The main argument I wish Ridley pursued more: How the very existence of civilization creates a mighty presumption against pessimism in all its forms. But I view his omission optimistically: The arguments for optimism are so numerous that no one book can contain them all.

Doomsayers are simple-minded extrapolators. I suspect that they have an aesthetic objection to population growth, which they wrap in pseudo-scientific garb. Like their close kin, anti-market politicians and pundits, doomsayers seem to have no conception of the power of human ingenuity to make life more livable — when that ingenuity is not stifled by government.

Related posts:

The Causes of Economic Growth

A Short Course in Economics

Addendum to a Short Course in Economics

The Price of Government

The Price of Government Redux

What Is Truth?

There are four kinds of truth: physical, logical-mathematical, psychological-emotional, and judgmental. The first two are closely related, as are the last two. After considering each of the two closely related pairs, I will link all four kinds of truth.

PHYSICAL AND LOGICAL-MATHEMATICAL TRUTH

Physical truth is, seemingly, the most straightforward of the lot. Physical truth seems to consist of that which humans are able to apprehend with their senses, aided sometimes by instruments. And yet, widely accepted notions of physical truth have changed drastically over the eons, not only because of improvements in the instruments of observation but also because of changes in the interpretation of data obtained with the aid of those instruments.

The latter point brings me to logical-mathematical truth. It is logic and mathematics that translates specific physical truths — or what are taken to be truths — into constructs (theories) such as quantum mechanics, general relativity, the Big Bang, and evolution. Of the relationship between specific physical truth and logical-mathematical truth, G.K. Chesterton said:

Logic and truth, as a matter of fact, have very little to do with each other. Logic is concerned merely with the fidelity and accuracy with which a certain process is performed, a process which can be performed with any materials, with any assumption. You can be as logical about griffins and basilisks as about sheep and pigs. On the assumption that a man has two ears, it is good logic that three men have six ears, but on the assumption that a man has four ears, it is equally good logic that three men have twelve. And the power of seeing how many ears the average man, as a fact, possesses, the power of counting a gentleman’s ears accurately and without mathematical confusion, is not a logical thing but a primary and direct experience, like a physical sense, like a religious vision. The power of counting ears may be limited by a blow on the head; it may be disturbed and even augmented by two bottles of champagne; but it cannot be affected by argument. Logic has again and again been expended, and expended most brilliantly and effectively, on things that do not exist at all. There is far more logic, more sustained consistency of the mind, in the science of heraldry than in the science of biology. There is more logic in Alice in Wonderland than in the Statute Book or the Blue Books. The relations of logic to truth depend, then, not upon its perfection as logic, but upon certain pre-logical faculties and certain pre-logical discoveries, upon the possession of those faculties, upon the power of making those discoveries. If a man starts with certain assumptions, he may be a good logician and a good citizen, a wise man, a successful figure. If he starts with certain other assumptions, he may be an equally good logician and a bankrupt, a criminal, a raving lunatic. Logic, then, is not necessarily an instrument for finding truth; on the contrary, truth is necessarily an instrument for using logic—for using it, that is, for the discovery of further truth and for the profit of humanity. Briefly, you can only find truth with logic if you have already found truth without it. [Thanks to The Fourth Checkraise for making me aware of Chesterton’s aperçu.]

To put it another way, logical-mathematical truth is only as valid as the axioms (principles) from which it is derived. Given an axiom, or a set of them, one can deduce “true” statements (assuming that one’s logical-mathematical processes are sound). But axioms are not pre-existing truths with independent existence (like Platonic ideals). They are products, in one way or another, of observation and reckoning. The truth of statements derived from axioms depends, first and foremost, on the truth of the axioms, which is the thrust of Chesterton’s aperçu.

It is usual to divide reasoning into two types of logical process:

- Induction is “The process of deriving general principles from particular facts or instances.” That is how scientific theories are developed, in principle. A scientist begins with observations and devises a theory from them. Or a scientist may begin with an existing theory, note that new observations do not comport with the theory, and devise a new theory to fit all the observations, old and new.

- Deduction is “The process of reasoning in which a conclusion follows necessarily from the stated premises; inference by reasoning from the general to the specific.” That is how scientific theories are tested, in principle. A theory (a “stated premise”) should lead to certain conclusions (“observations”). If it does not, the theory is falsified. If it does, the theory lives for another day.

But the stated premises (axioms) of a scientific theory (or exercise in logic or mathematical operation) do not arise out of nothing. In one way or another, directly or indirectly, they are the result of observation and reckoning (induction). Get the observation and reckoning wrong, and what follows is wrong; get them right and what follows is right. Chesterton, again.

PSYCHOLOGICAL-EMOTIONAL AND JUDGMENTAL TRUTH

A psychological-emotional truth is one that depends on more than physical observations. A judgmental truth is one that arises from a psychological-emotional truth and results in a consequential judgment about its subject.

A common psychological-emotional truth, one that finds its way into judgmental truth, is an individual’s conception of beauty. The emotional aspect of beauty is evident in the tendency, especially among young persons, to consider their lovers and spouses beautiful, even as persons outside the intimate relationship would find their judgments risible.

A more serious psychological-emotional truth — or one that has public-policy implications — has to do with race. There are persons who simply have negative views about races other than their own, for reasons that are irrelevant here. What is relevant is the close link between the psychological-emotional views about persons of other races — that they are untrustworthy, stupid, lazy, violent, etc. — and judgments that adversely affect those persons. Those judgments range from refusal to hire a person of a different race (still quite common, if well disguised to avoid legal problems) to the unjust convictions and executions because of prejudices held by victims, witnesses, police officers, prosecutors, judges, and jurors. (My examples point to anti-black prejudices on the part of whites, but there are plenty of others to go around: anti-white, anti-Latino, anti-Asian, etc. Nor do I mean to impugn prudential judgments that implicate race, as in the avoidance by whites of certain parts of a city.)

A close parallel is found in the linkage between the psychological-emotional truth that underlies a jury’s verdict and the legal truth of a judge’s sentence. There is an even tighter linkage between psychological-emotional truth and legal truth in the deliberations and rulings of higher courts, which operated without juries.

PUTTING TRUTH AND TRUTH TOGETHER

Psychological-emotional proclivities, and the judgmental truths that arise from them, impinge on physical and mathematical-logical truth. Because humans are limited (by time, ability, and inclination), they often accept as axiomatic statements about the world that are tenuous, if not downright false. Scientists, mathematicians, and logicians are not exempt from the tendency to credit dubious statements. And that tendency can arise not just from expediency and ignorance but also from psychological-emotional proclivities.

Albert Einstein, for example, refused to believe that very small particles of matter-energy (quanta) behave probabilistically, as described by the branch of physics known as quantum mechanics. Put simply, sub-atomic particles do not seem to behave according to the same physical laws that describe the actions of the visible universe; their behavior is discontinuous (“jumpy”) and described probabilistically, not by the kinds of continuous (“smooth”) mathematical formulae that apply to the macroscopic world.

Einstein refused to believe that different parts of the same universe could operate according to different physical laws. Thus he saw quantum mechanics as incomplete and in need of reconciliation with the rest of physics. At one point in his long-running debate with the defenders of quantum mechanics, Einstein wrote: “I, at any rate, am convinced that He [God] does not throw dice.” And yet, quantum mechanics — albeit refined and elaborated from the version Einstein knew — survives and continues to describe the sub-atomic world with accuracy.

Ironically, Einstein’s two greatest contributions to physics — special and general relativity — were met with initial skepticism by other physicists. Special relativity rejects absolute space-time; general relativity depicts a universe whose “shape” depends on the masses and motions of the bodies within it. These are not intuitive concepts, given man’s instinctive preference for certainty.

The point of the vignettes about Einstein is that science is not a sterile occupation; it can be (and often is) fraught with psychological-emotional visions of truth. What scientists believe to be true depends, to some degree, on what they want to believe is true. Scientists are simply human beings who happen to be more capable than the average person when it comes to the manipulation of abstract concepts. And yet, scientists are like most of their fellow beings in their need for acceptance and approval. They are fully capable of subscribing to a “truth” if to do otherwise would subject them to the scorn of their peers. Einstein was willing and able to question quantum mechanics because he had long since established himself as a premier physicist, and because he was among that rare breed of humans who are (visibly) unaffected by the opinions of their peers.

Such are the scientists who, today, question their peers’ psychological-emotional attachment to the hypothesis of anthropogenic global warming (AGW). The questioners are not “deniers” or “skeptics”; they are scientists who are willing to look deeper than the facile hypothesis that, more than two decades ago, gave rise to the AGW craze.

It was then that a scientist noted the coincidence of an apparent rise in global temperatures since the late 1800s (or is it since 1975?) and an apparent increase in the atmospheric concentration of CO2. And thus a hypothesis was formed. It was embraced and elaborated by scientists (and others) eager to be au courant, to obtain government grants (conveniently aimed at research “proving” AGW), to be “right” by being in the majority, and — let it be said — to curtail or stamp out human activities which they find unaesthetic. Evidence to the contrary be damned.

Where else have we seen this kind of behavior, albeit in a more murderous guise? At the risk of invoking Hitler, I must answer with this link: Nazi Eugenics. Again, science is not a sterile occupation, exempt from human flaws and foibles.

CONCLUSION

What is truth? Is it an absolute reality that lies beyond human perception? Is it those “answers” that flow logically or mathematically from unproven assumptions? Is it the “answers” that, in some way, please us? Or is it the ways in which we reshape the world to conform it with those “answers”?

Truth, as we are able to know it, is like the human condition: fragile and prone to error.

Cornered by Gender?

Tanya Khovanova, writing at her math blog, plays a variation on a theme introduced by her guest blogger, Rebecca Frankel, about three weeks ago. Frankel, as I note in “Sexist Nonsense,” wants to redefine gender to exclude two things that make a big difference between males and females: testosterone and estrogen. By Frankel’s logic, males and females would be equal in ability, if only it weren’t for that pesky matter of gender. As I put it in “Sexist Nonsense,”

So “ability” now has a new definition. It is a hypothetical state of equality that is disturbed by a natural difference between males and females. And the fact that this natural difference has an influence on performance is somehow “proof” that males and females are born equally able. By that kind of reasoning, the fact that I cannot see well enough to hit a major-league fastball proves that I belong in the Hall of Fame, along with Babe Ruth. If you’re looking for “sexist nonsense,” look no further than Rebecca Frankel’s hypothesis.