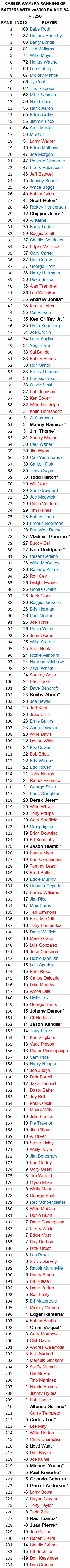

In this post, I look at the batting records of the 136 position players who accrued most or all of their playing time between 1901 and 2015. With the exception of a bulge in the .340-.345 range, the frequency distribution of lifetime averages for those 136 players looks like a rather ragged normal distribution:

That’s Ty Cobb (.366) at the left, all by himself (1 person = 0.7 percent of the 136 players considered here). To Cobb’s right, also by himself, is Rogers Hornsby (.358). The next solo slot to the right of Hornsby’s belongs to Ed Delahanty (.346). The bulge between .340 and .345 is occupied by Tris Speaker, Billy Hamilton, Ted Williams, Babe Ruth, Harry Heilmann, Bill Terry, Willie Keeler, George Sisler, and Lou Gehrig. At the other end, in the anchor slot, is Ray Schalk (.253), to his left in the next slot are Harmon Killebrew (.256) and Rabbit Maranville (.258). The group in the .260-.265 column comprises Gary Carter, Joe Tinker, Luis Aparacio, Ozzie Smith, Reggie Jackson, and Bill Mazeroski.

Players with relatively low batting averages — Schalk, Killibrew, etc. — are in the Hall of Fame because of their prowess as fielders or home-run hitters. Many of the high-average players were also great fielders or home-run hitters (or both). In any event, for your perusal here’s the complete list of 136 position players under consideration in this post:

For the next exercise, I normalized the Hall of Famers’ single-season averages, as discussed here. I included only those seasons in which a player qualified for that year’s batting championship by playing in enough games, compiling enough plate appearances, or attaining enough at-bats (the criteria have varied).

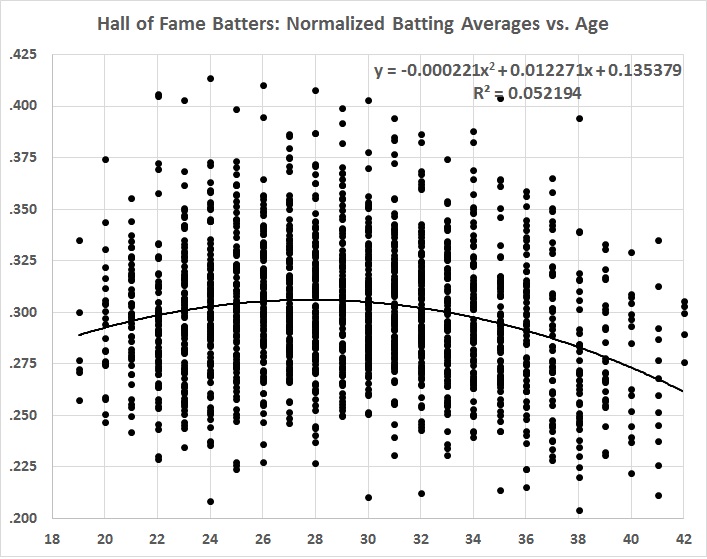

For the years 1901-2015, the Hall-of-Famers considered here compiled 1,771 seasons in which they qualified for the batting title. (That’s 13 percent of the 13,463 batting-championship-qualifying seasons compiled by all major leaguers in 1901-2015.) Plotting the Hall-of-Famers’ normalized single-season averages against age, I got this:

The r-squared value of the polynomial fit, though low, is statistically significant (p<.01). The equation yields the following information:

The green curve traces the difference between the mean batting average at a given age and the mean batting average at the mean peak age, which is 28.3. For example, by the equation, the average Hall of Famer batted .2887 at age 19, and .3057 at age 28.3 — a rise of .0017 over 9.3 years.

The black line traces the change in the mean batting average from age to age; the increase is positive, though declining from ages 20 through 28, then negative (and still declining) through the rest of the average Hall of Famer’s career.

The red line represents the change in the rate of change, which is constant at -.00044 points (-4.4 percent) a year.

In tabular form:

Finally, I should note that the combined lifetime batting average of the 136 players is .302, as against the 1901-2015 average of .262 for all players. In other words, the Hall of Famers hit safely in 30.2 percent of at-bats; all players hit safely in 26.2 percent of at-bats. What’s the big deal about 4 percentage points?

To find out, I consulted “Back to Baseball,” in which I found the significant determinants of run-scoring. In the years 1901-1919 (the “dead ball” era), a 4 percentage-point (.040) rise in batting average meant, on average, an increase in runs scored per 9 innings of 1.18. That’s a significant jump in offensive output, given that the average number of runs scored per 9 innings was 3.97 in 1901-1919.

For 1920-2015, a rise in batting average of 4 percentage points meant, on average, an increase in runs scored per 9 innings of 1.03, as against an average number of runs scored per 9 innings of 4.51. That’s also significant, and it doesn’t include the effect of extra-base hits, which Hall of Famers produced at a greater rate than other players.

So Hall of Famers, on the whole, certainly made greater offensive contributions than other players, and some of them were peerless in the field. But do all Hall of Famers really belong in the Hall? No, but that’s the subject of another post.