This is aimed at writers of non-fiction works, but writers of fiction may also find it helpful. There are four parts:

I. Some Writers to Heed and Emulate

A. The Essentials: Lucidity, Simplicity, Euphony

B. Writing Clearly about a Difficult Subject

C. Advice from an American Master

D. Also Worth a Look

II. Step by Step

A. The First Draft

1. Decide — before you begin to write — on your main point and your purpose for making it.

2. Avoid wandering from your main point and purpose; use an outline.

3. Start by writing an introductory paragraph that summarizes your “story line”.

4. Lay out a straight path for the reader.

5. Know your audience, and write for it.

6. Facts are your friends — unless you’re trying to sell a lie, of course.

7. Momentum is your best friend.

B. From First Draft to Final Version

1. Your first draft is only that — a draft.

2. Where to begin? Stand back and look at the big picture.

3. Nit-picking is important.

4. Critics are necessary, even if not mandatory.

5. Accept criticism gratefully and graciously.

6. What if you’re an independent writer and have no one to turn to?

7. How many times should you revise your work before it’s published?

III. Reference Works

A. The Elements of Style

B. Eats, Shoots & Leaves

C. Follett’s Modern American Usage

D. Garner’s Modern American Usage

E. A Manual of Style and More

IV. Notes about Grammar and Usage

A. Stasis, Progress, Regress, and Language

B. Illegitimi Non Carborundum Lingo

1. Eliminate filler words.

2. Don’t abuse words.

3. Punctuate properly.

4. Why ‘s matters, or how to avoid ambiguity in possessives.

5. Stand fast against political correctness.

6. Don’t split infinitives.

7. It’s all right to begin a sentence with “And” or “But” — in moderation.

8. There’s no need to end a sentence with a preposition.

Some readers may conclude that I prefer stodginess to liveliness. That’s not true, as any discerning reader of this blog will know. I love new words and new ways of using words, and I try to engage readers while informing and persuading them. But I do those things within the expansive boundaries of prescriptive grammar and usage. Those boundaries will change with time, as they have in the past. But they should change only when change serves understanding, not when it serves the whims of illiterates and language anarchists.

This guide is long because It covers a lot of topics aside from the essentials of clear writing. The best concise guide to clear writing that I’ve come across is by David Randall: “Twenty-five Guidelines for Writing Prose” (National Association of Scholars).

I. SOME WRITERS TO HEED AND EMULATE

A. The Essentials: Lucidity, Simplicity, Euphony

I begin with the insights of a great writer, W. Somerset Maugham (English, 1874-1965). Maugham was a prolific and popular playwright, novelist, short-story writer, and author of non-fiction works. He reflected on his life and career as a writer in The Summing Up. It appeared in 1938, when Maugham was 64 years old and more than 40 years into his very long career. I first read The Summing Up about 40 years ago, and immediately became an admirer of Maugham’s candor and insight. This led me to become an avid reader of Maugham’s novels and short-story collections. And I have continued to consult The Summing Up for booster shots of Maugham’s wisdom.

Maugham’s advice to “write lucidly, simply, euphoniously and yet with liveliness” is well-supported by examples and analysis. I offer the following excerpts of the early pages of The Summing Up, where Maugham discusses the craft of writing:

I have never had much patience with the writers who claim from the reader an effort to understand their meaning…. There are two sorts of obscurity that you find in writers. One is due to negligence and the other to wilfulness. People often write obscurely because they have never taken the trouble to learn to write clearly. This sort of obscurity you find too often in modern philosophers, in men of science, and even in literary critics. Here it is indeed strange. You would have thought that men who passed their lives in the study of the great masters of literature would be sufficiently sensitive to the beauty of language to write if not beautifully at least with perspicuity. Yet you will find in their works sentence after sentence that you must read twice to discover the sense. Often you can only guess at it, for the writers have evidently not said what they intended.

Another cause of obscurity is that the writer is himself not quite sure of his meaning. He has a vague impression of what he wants to say, but has not, either from lack of mental power or from laziness, exactly formulated it in his mind and it is natural enough that he should not find a precise expression for a confused idea. This is due largely to the fact that many writers think, not before, but as they write. The pen originates the thought…. From this there is only a little way to go to fall into the habit of setting down one’s impressions in all their original vagueness. Fools can always be found to discover a hidden sense in them….

Simplicity is not such an obvious merit as lucidity. I have aimed at it because I have no gift for richness. Within limits I admire richness in others, though I find it difficult to digest in quantity. I can read one page of Ruskin with delight, but twenty only with weariness. The rolling period, the stately epithet, the noun rich in poetic associations, the subordinate clauses that give the sentence weight and magnificence, the grandeur like that of wave following wave in the open sea; there is no doubt that in all this there is something inspiring. Words thus strung together fall on the ear like music. The appeal is sensuous rather than intellectual, and the beauty of the sound leads you easily to conclude that you need not bother about the meaning. But words are tyrannical things, they exist for their meanings, and if you will not pay attention to these, you cannot pay attention at all. Your mind wanders…..

But if richness needs gifts with which everyone is not endowed, simplicity by no means comes by nature. To achieve it needs rigid discipline…. To my mind King James’s Bible has been a very harmful influence on English prose. I am not so stupid as to deny its great beauty, and it is obvious that there are passages in it of a simplicity which is deeply moving. But the Bible is an oriental book. Its alien imagery has nothing to do with us. Those hyperboles, those luscious metaphors, are foreign to our genius…. The plain, honest English speech was overwhelmed with ornament. Blunt Englishmen twisted their tongues to speak like Hebrew prophets. There was evidently something in the English temper to which this was congenial, perhaps a native lack of precision in thought, perhaps a naive delight in fine words for their own sake, an innate eccentricity and love of embroidery, I do not know; but the fact remains that ever since, English prose has had to struggle against the tendency to luxuriance…. It is obvious that the grand style is more striking than the plain. Indeed many people think that a style that does not attract notice is not style…. But I suppose that if a man has a confused mind he will write in a confused way, if his temper is capricious his prose will be fantastical, and if he has a quick, darting intelligence that is reminded by the matter in hand of a hundred things he will, unless he has great self-control, load his pages with metaphor and simile….

Whether you ascribe importance to euphony … must depend on the sensitiveness of your ear. A great many readers, and many admirable writers, are devoid of this quality. Poets as we know have always made a great use of alliteration. They are persuaded that the repetition of a sound gives an effect of beauty. I do not think it does so in prose. It seems to me that in prose alliteration should be used only for a special reason; when used by accident it falls on the ear very disagreeably. But its accidental use is so common that one can only suppose that the sound of it is not universally offensive. Many writers without distress will put two rhyming words together, join a monstrous long adjective to a monstrous long noun, or between the end of one word and the beginning of another have a conjunction of consonants that almost breaks your jaw. These are trivial and obvious instances. I mention them only to prove that if careful writers can do such things it is only because they have no ear. Words have weight, sound and appearance; it is only by considering these that you can write a sentence that is good to look at and good to listen to.

I have read many books on English prose, but have found it hard to profit by them; for the most part they are vague, unduly theoretical, and often scolding. But you cannot say this of Fowler’s Dictionary of Modern English Usage. It is a valuable work. I do not think anyone writes so well that he cannot learn much from it. It is lively reading. Fowler liked simplicity, straightforwardness and common sense. He had no patience with pretentiousness. He had a sound feeling that idiom was the backbone of a language and he was all for the racy phrase. He was no slavish admirer of logic and was willing enough to give usage right of way through the exact demesnes of grammar. English grammar is very difficult and few writers have avoided making mistakes in it….

But Fowler had no ear. He did not see that simplicity may sometimes make concessions to euphony. I do not think a far-fetched, an archaic or even an affected word is out of place when it sounds better than the blunt, obvious one or when it gives a sentence a better balance. But, I hasten to add, though I think you may without misgiving make this concession to pleasant sound, I think you should make none to what may obscure your meaning. Anything is better than not to write clearly. There is nothing to be said against lucidity, and against simplicity only the possibility of dryness. This is a risk that is well worth taking when you reflect how much better it is to be bald than to wear a curly wig. But there is in euphony a danger that must be considered. It is very likely to be monotonous…. I do not know how one can guard against this. I suppose the best chance is to have a more lively faculty of boredom than one’s readers so that one is wearied before they are. One must always be on the watch for mannerisms and when certain cadences come too easily to the pen ask oneself whether they have not become mechanical. It is very hard to discover the exact point where the idiom one has formed to express oneself has lost its tang….

If you could write lucidly, simply, euphoniously and yet with liveliness you would write perfectly: you would write like Voltaire. And yet we know how fatal the pursuit of liveliness may be: it may result in the tiresome acrobatics of Meredith. Macaulay and Carlyle were in their different ways arresting; but at the heavy cost of naturalness. Their flashy effects distract the mind. They destroy their persuasiveness; you would not believe a man was very intent on ploughing a furrow if he carried a hoop with him and jumped through it at every other step. A good style should show no sign of effort. What is written should seem a happy accident…. [Pp. 23-32, passim, Pocket Book edition, 1967]

You should also study Maugham’s The Summing Up for its straightforward style. I return to these opening sentences of a paragraph:

Another cause of obscurity is that the writer is himself not quite sure of his meaning. He has a vague impression of what he wants to say, but has not, either from lack of mental power or from laziness, exactly formulated it in his mind and it is natural enough that he should not find a precise expression for a confused idea. This is due largely to the fact that many writers think, not before, but as they write. The pen originates the thought…. [Pp. 23-24]

This is a classic example of good writing (and it conveys excellent advice). The first sentence states the topic of the paragraph. The following sentences elaborate it. Each sentence is just long enough to convey a single, complete thought. Because of that, even the rather long second sentence in the second block quotation should be readily understood by a high-school graduate (a graduate of a small-city high school in the 1950s, at least).

B. Writing Clearly about a Difficult Subject

I offer a great English mathematician, G.H. Hardy, as a second exemplar. In particular, I recommend Hardy’s A Mathematician’s Apology. (It’s an apology in the sense of “a formal written defense of something you believe in strongly”, where the something is the pursuit of pure mathematics.) The introduction by C.P Snow is better than Hardy’s long essay, but Snow was a published novelist as well as a trained scientist. Hardy’s publications, other than the essay, are mathematical. The essay is notable for its accessibility, even to non-mathematicians. Of its 90 pages, only 23 (clustered near the middle) require a reader to cope with mathematics, but it’s mathematics that shouldn’t daunt a person who has taken and passed high-school algebra.

Hardy’s prose is flawed, to be sure. He overuses shudder quotes, and occasionally gets tangled in a too-long sentence. But I’m taken by his exposition of the art of doing higher mathematics, and the beauty of doing it well. Hardy, in other words, sets an example to be followed by writers who wish to capture the essence of a technical subject and convey that essence to intelligent laymen.

Here are some samples:

There are many highly respectable motives which may lead men to prosecute research, but three which are much more important than the rest. The first (without which the rest must come to nothing) is intellectual curiosity, desire to know the truth. Then, professional pride, anxiety to be satisfied with one’s performance, the shame that overcomes any self-respecting craftsman when his work is unworthy of his talent. Finally, ambition, desire for reputation, and the position, even the power or the money, which it brings. It may be fine to feel, when you have done your work, that you have added to the happiness or alleviated the sufferings of others, but that will not be why you did it. So if a mathematician, or a chemist, or even a physiologist, were to tell me that the driving force in his work had been the desire to benefit humanity, then I should not believe him (nor should I think any better of him if I did). His dominant motives have been those which I have stated and in which, surely, there is nothing of which any decent man need be ashamed. [Pp. 78-79, 1979 paperback edition]

* * *

A mathematician, like a painter or a poet, is a maker of patterns. If his patterns are more permanent than theirs, it is because they are made with ideas. A painter makes patters with shapes and colors, a poet with words. A painting may embody an ‘idea’, but the idea is usually commonplace and unimportant. In poetry, ideas count for a good deal more; but, as Housman insisted, the importance of ideas in poetry is habitually exaggerated…

… A mathematician, on the other hand, has no material to work with but ideas, and his patterns are likely to last longer, since ideas wear less with time than words. [Pp. 84-85]

C. Advice from an American Master

A third exemplar is E.B. White, a successful writer of fiction who is probably best known for The Elements of Style. (It’s usually called “Strunk & White” or “the little book”.) It’s an outgrowth of a slimmer volume of the same name by William Strunk Jr. (Strunk had been dead for 13 years when White produced the first edition of Strunk & White.)

I’ll address the little book’s authoritativeness in a later section. Here, I’ll highlight White’s style of writing. This is from the introduction to the third edition (the last one edited by White):

The Elements of Style, when I re-examined it in 1957, seemed to me to contain rich deposits of gold. It was Will Strunk’s parvum opus, his attempt to cut the vast tangle of English rhetoric down to size and write its rules and principles on the head of a pin. Will himself had hung the tag “little” on the book; he referred to it sardonically and with secret pride as “the little book,” always giving the word “little” a special twist, as though he were putting a spin on a ball. In its original form, it was forty-three-page summation of the case for cleanliness, accuracy, and brevity in the use of English…. [P. xi]

Vivid, direct, and engaging. And the whole book reads like that.

D. Also Worth a Look

Read Steven Pinker‘s essay, “Why Academics Stink at Writing” (The Chronicle Review, September 26, 2014). You may not be an academic, but I’ll bet that you sometimes lapse into academese. (I know that I sometimes do.) Pinker’s essay will help you to recognize academese, and to understand why it’s to be avoided.

Pinker’s essay also appears in a booklet, “Why Academics Stink at Writing–and How to Fix It”, which is available here in exchange for your name, your job title, the name of your organization, and your e-mail address. (Whether you wish to give true information is up to you.) Of the four essays that follow Pinker’s, I prefer the one by Michael Munger.

Beyond that, pick and chose by searching on “writers on writing”. Google gave me 391,000 hits on the day that I published this post. Hidden among the dross, I found this, which led me to this gem: “George Orwell on Writing, How to Counter the Mindless Momentum of Language, and the Four Questions a Great Writer Must Ask Herself”. (“Herself”? I’ll say something about gender in part IV.)

II. STEP BY STEP

A. The First Draft

1. Decide — before you begin to write — on your main point and your purpose for making it.

Can you state your main point in a sentence? If you can’t, you’re not ready to write about whatever it is that’s on your mind.

Your purpose for writing about a particular subject may be descriptive, explanatory, or persuasive. An economist may, for example, begin an article by describing the state of the economy, as measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP). He may then explain that the rate of growth in GDP has receded since the end of World War II, because of greater government spending and the cumulative effect of regulatory activity. He is then poised to make a case for less spending and for the cancellation of regulations that impede economic growth.

2. Avoid wandering from your main point and purpose; use an outline.

You can get by with a bare outline, unless you’re writing a book, a manual, or a long article. Fill the outline as you go. Change the outline if you see that you’ve omitted a step or put some steps in the wrong order. But always work to an outline, however sketchy and malleable it may be. (The outline may be a mental one if you are deeply knowledgeable about the material you’re working with.)

3. Start by writing an introductory paragraph that summarizes your “story line”.

The introductory paragraph in a news story is known as “the lead” or “the lede” (a spelling that’s meant to convey the correct pronunciation). A classic lead gives the reader the who, what, why, when, where, and how of the story. As noted in Wikipedia, leads aren’t just for journalists:

Leads in essays summarize the outline of the argument and conclusion that follows in the main body of the essay. Encyclopedia leads tend to define the subject matter as well as emphasize the interesting points of the article. Features and general articles in magazines tend to be somewhere between journalistic and encyclopedian in style and often lack a distinct lead paragraph entirely. Leads or introductions in books vary enormously in length, intent and content.

Think of the lead as a target toward which you aim your writing. You should begin your first draft with a lead, even if you later decide to eliminate, prune, or expand it.

4. Lay out a straight path for the reader.

You needn’t fill your outline sequentially, but the outline should trace a linear progression from statement of purpose to conclusion or call for action. Trackbacks and detours can be effective literary devices in the hands of a skilled writer of fiction. But you’re not writing fiction, let alone mystery fiction. So just proceed in a straight line, from beginning to end.

Quips, asides, and anecdotes should be used sparingly, and only if they reinforce your message and don’t distract the reader’s attention from it.

5. Know your audience, and write for it.

I aim at readers who can grasp complex concepts and detailed arguments. But if you’re writing something like a policy manual for employees at all levels of your company, you’ll want to keep it simple and well-marked: short words, short sentences, short paragraphs, numbered sections and sub-sections, and so on.

6. Facts are your friends — unless you’re trying to sell a lie, of course.

Unsupported generalities will defeat your purpose, unless you’re writing for a gullible, uneducated audience. Give concrete examples and cite authoritative references. If your work is technical, show your data and calculations, even if you must put the details in footnotes or appendices to avoid interrupting the flow of your argument. Supplement your words with tables and graphs, if possible, but make them as simple as you can without distorting the underlying facts.

7. Momentum is your best friend.

Write a first draft quickly, even if you must leave holes to be filled later. I’ve always found it easier to polish a rough draft that spans the entire outline than to work from a well-honed but unaccompanied introductory section.

B. From First Draft to Final Version

1. Your first draft is only that — a draft.

Unless you’re a prodigy, you’ll have to do some polishing (probably a lot) before you have something that a reader can follow with ease.

2. Where to begin? Stand back and look at the big picture.

Is your “story line” clear? Are your points logically connected? Have you omitted key steps or important facts? If you find problems, fix them before you start nit-picking your grammar, syntax, and usage.

3. Nit-picking is important.

Errors of grammar, syntax, and usage can (and probably will) undermine your credibility. Thus, for example, subject and verb must agree (“he says” not “he say”); number must be handled correctly (“there are two” not “there is two”); tense must make sense (“the shirt shrank” not “the shirt shrunk”); usage must be correct (“its” is the possessive pronoun, “it’s” is the contraction for “it is”).

4. Critics are necessary, even if not mandatory.

Unless you’re a skilled writer and objective self-critic, you should ask someone to review your work before you publish it or submit it for publication. If your work must be reviewed by a boss or an editor, count yourself lucky. Your boss is responsible for the quality of your work; he therefore has a good reason to make it better (unless he’s a jerk or psychopath). If your editor isn’t qualified to do substantive editing, he can at least correct your syntax, grammar, and usage.

5. Accept criticism gratefully and graciously.

Bad writers don’t, which is why they remain bad writers. Yes, you should reject (or fight against) changes and suggestions if they are clearly wrong, and if you can show that they’re wrong. But if your critic tells you that your logic is muddled, your facts are inapt, and your writing stinks (in so many words), chances are that your critic is right. And you’ll know that your critic is dead right if your defense (perhaps unvoiced) is “That’s just my style of writing.”

6. What if you’re an independent writer and have no one to turn to?

Be your own worst critic. If you have the time, let your first draft sit for a day or two before you return to it. Then look at it as if you’d never seen it before, as if someone else had written it. Ask yourself if it makes sense, if every key point is well-supported, and if key points are missing, Look for glaring errors in syntax, grammar, and usage. (I’ll list and discuss some useful reference works in part III.) If you can’t find any problems or more than trivial ones, you shouldn’t be a self-critic — and you’re probably a terrible writer. If you make extensive revisions, you’re on the way to become an excellent writer.

7. How many times should you revise your work before it’s published?

That depends, of course, on the presence or absence of a deadline. The deadline may be a formal one, geared to a production schedule. Or it may be an informal but real one, driven by current events (e.g., the need to assess a new economics text while it’s in the news). But even without a deadline, two revisions of a rough draft should be enough. A piece that’s rewritten several times can lose its (possessive pronoun) edge. And unless you’re an amateur with time to spare (e.g., a blogger like me), every rewrite represents a forgone opportunity to begin a new work.

III. REFERENCE WORKS

A. The Elements of Style

If you could have only one book to help you write better, it would be The Elements of Style. Admittedly, Strunk & White, as the book is also known, has a vociferous critic, one Geoffrey K. Pullum. But Pullum documents only one substantive flaw: an apparent mischaracterization of what constitutes the passive voice. What Pullum doesn’t say is that the book correctly flays the kind of writing that it calls passive (correctly or not). Further, Pullum derides the book’s many banal headings, while ignoring what follows them: sound advice, backed by concrete examples. (There’s a nice rebuttal of Pullum here.) It’s evident that the book’s real sin — in Pullum’s view — is “bossiness” (prescriptivism), which is no sin at all, as I’ll explain in part IV.

There are so many good writing tips in Strunk & White that it was hard for me to choose a sample. I randomly chose “Omit Needless Words” (one of the headings derided by Pullum), which opens with a statement of principles:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine to unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all of his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell. [P. 23]

That would be empty rhetoric, were it not followed by further discussion and 17 specific examples. Here are a few:

- the question as to whether should be replaced by whether or the question whether

- the reason why is that should be replaced by because

- I was unaware of the fact that should be replace by I was unaware that or I did not know that

- His brother, who is a member of the same firm should be replaced by His brother, a member of the same firm [P. 24]

There’s much more than that to Strunk & White, of course, (Go here to see table of contents.) You’ll become a better writer — perhaps an excellent one — if you carefully read Strunk & White, re-read it occasionally, and apply the principles that it espouses and illustrates.

B. Eats, Shoots & Leaves

After Strunk & White, my favorite instructional work is Lynne Truss‘s Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero-Tolerance Approach to Punctuation. I vouch for the accuracy of this description of the book (Publishers Weekly via Amazon.com):

Who would have thought a book about punctuation could cause such a sensation? Certainly not its modest if indignant author, who began her surprise hit motivated by “horror” and “despair” at the current state of British usage: ungrammatical signs (“BOB,S PETS”), headlines (“DEAD SONS PHOTOS MAY BE RELEASED”) and band names (“Hear’Say”) drove journalist and novelist Truss absolutely batty. But this spirited and wittily instructional little volume, which was a U.K. #1 bestseller, is not a grammar book, Truss insists; like a self-help volume, it “gives you permission to love punctuation.” Her approach falls between the descriptive and prescriptive schools of grammar study, but is closer, perhaps, to the latter. (A self-professed “stickler,” Truss recommends that anyone putting an apostrophe in a possessive “its”-as in “the dog chewed it’s bone”-should be struck by lightning and chopped to bits.) Employing a chatty tone that ranges from pleasant rant to gentle lecture to bemused dismay, Truss dissects common errors that grammar mavens have long deplored (often, as she readily points out, in isolation) and makes elegant arguments for increased attention to punctuation correctness: “without it there is no reliable way of communicating meaning.” Interspersing her lessons with bits of history (the apostrophe dates from the 16th century; the first semicolon appeared in 1494) and plenty of wit, Truss serves up delightful, unabashedly strict and sometimes snobby little book, with cheery Britishisms (“Lawks-a-mussy!”) dotting pages that express a more international righteous indignation.

C. Follett’s Modern American Usage

Next up is Wilson Follett’s Modern American Usage: A Guide. The link points to a newer edition than the one that I’ve relied on for about 50 years. Reviews of the newer edition, edited by one Erik Wensberg, are mixed but generally favorable. However, the newer edition seems to lack Follett’s “Introductory” which is divided into “Usage, Purism, and Pedantry” and “The Need of an Orderly Mind”. If that is so, the newer edition is likely to be more compromising toward language relativists like Geoffrey Pullum. The following quotations from Follett’s “Introductory” (one from each section), will give you an idea of Follett’s stand on relativism:

[F]atalism about language cannot be the philosophy of those who care abut language; it is the illogical philosophy of their opponents. Surely the notion that, because usage is ultimately what everybody does to words, nobody can or should do anything about them is self-contradictory. Somebody, by definition does something, and this something is best done by those with convictions and a stake in the outcome, whether the stake of private pleasure or of professional duty or both does not matter. Resistance always begins with individuals. [Pp. 12-3]

* * *

A great deal of our language is so automatic that even the thoughtful never think about it, and this mere not-thinking is the gate through which solecisms or inferior locutions slip in. Some part, greater or smaller, of every thousand words is inevitably parroted, even by the least parrotlike. [P. 14]

(A reprint of the original edition is available here.)

D. Garner’s Modern American Usage

I also like Garner’s Modern American Usage, by Bryan A. Garner. Though Garner doesn’t write as elegantly as Follett, he is just as tenacious and convincing as Follett in defense of prescriptivism. And Garner’s book far surpasses Follett’s in scope and detail; it’s twice the length, and the larger pages are set in smaller type.

E. A Manual of Style and More

I have one more book to recommend: The Chicago Manual of Style. Though the book is a must-have for editors, serious writers should also own a copy and consult it often. If you’re unfamiliar with the book, you can get an idea of its vast range and depth of coverage by following the preceding link, clicking on “Look inside”, and perusing the table of contents, first pages, and index.

Every writer should have a good dictionary and thesaurus at hand. I use The Free Dictionary, and am seldom disappointed by it. There also look promising: Dictionary.com and Merriam-Webster.

IV. NOTES ABOUT GRAMMAR AND USAGE

This part delivers some sermons about practices to follow if you wish to communicate effectively and be taken seriously, and if you wish not to be thought of as a semi-literate, self-indulgent, faddish dilettante. Section A is a defense of prescriptivism in language. Section B (the title of which is mock-Latin for “Don’t Let the Bastards Wear Down the Language”) counsels steadfastness in the face of political correctness and various sloppy usages.

A. Stasis, Progress, Regress, and Language

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven…. — Ecclesiastes 3:1 (King James Bible)

Nothing man-made is permanent; consider, for example, the list of empires here. In spite of the history of empires — and other institutions and artifacts of human endeavor — most people seem to believe that the future will be much like the present. And if the present embodies progress of some kind, most people seem to expect that progress to continue.

Things do not simply go on as they have been without the expenditure of requisite effort. Take the Constitution’s broken promises of liberty, about which I have written so much. Take the resurgence of Russia as a rival for international influence. This has been in the works for about 25 years, but didn’t register on most Americans until the Crimean crisis and the invasion of Ukraine. What did Americans expect? That the U.S. could remain the unchallenged superpower while reducing its armed forces to the point that they were strained by relatively small wars in Afghanistan and Iraq? That Vladimir Putin would be cowed by American presidents who had so blatantly advertised their hopey-changey attitudes toward Iran and Islam, while snubbing a traditional ally like Israel, failing to beef up America’s armed forces, and allowing America’s industrial capacity to wither in the name of “globalaism” (or whatever the current catch-phrase may be)?

Turning to naïveté about progress, I offer Steven Pinker’s fatuous The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. Pinker tries to show that human beings are becoming kinder and gentler. I have much to say in another post about Pinker’s thesis. One of my sources is Robert Epstein’s review of Pinker’s book. This passage is especially apt:

The biggest problem with the book … is its overreliance on history, which, like the light on a caboose, shows us only where we are not going. We live in a time when all the rules are being rewritten blindingly fast—when, for example, an increasingly smaller number of people can do increasingly greater damage. Yes, when you move from the Stone Age to modern times, some violence is left behind, but what happens when you put weapons of mass destruction into the hands of modern people who in many ways are still living primitively? What happens when the unprecedented occurs—when a country such as Iran, where women are still waiting for even the slightest glimpse of those better angels, obtains nuclear weapons? Pinker doesn’t say.

Less important in the grand scheme, but no less wrong-headed, is the idea of limitless progress in the arts. To quote myself:

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the visual, auditory, and verbal arts became an “inside game”. Painters, sculptors, composers (of “serious” music), choreographers, and writers of fiction began to create works not for the enjoyment of audiences but for the sake of exploring “new” forms. Given that the various arts had been perfected by the early 1900s, the only way to explore “new” forms was to regress toward primitive ones — toward a lack of structure…. Aside from its baneful influence on many true artists, the regression toward the primitive has enabled persons of inferior talent (and none) to call themselves “artists”. Thus modernism is banal when it is not ugly.

Painters, sculptors, etc., have been encouraged in their efforts to explore “new” forms by critics, by advocates of change and rebellion for its own sake (e.g., “liberals” and “bohemians”), and by undiscriminating patrons, anxious to be au courant. Critics have a special stake in modernism because they are needed to “explain” its incomprehensibility and ugliness to the unwashed.

The unwashed have nevertheless rebelled against modernism, and so its practitioners and defenders have responded with condescension, one form of which is the challenge to be “open minded” (i.e., to tolerate the second-rate and nonsensical). A good example of condescension is heard on Composers Datebook, a syndicated feature that runs on some NPR stations. Every Composers Datebook program closes by “reminding you that all music was once new.” As if to lump Arnold Schoenberg and John Cage with Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven.

All music, painting, sculpture, dance, and literature was once new, but not all of it is good. Much (most?) of what has been produced since 1900 is inferior, self-indulgent crap.

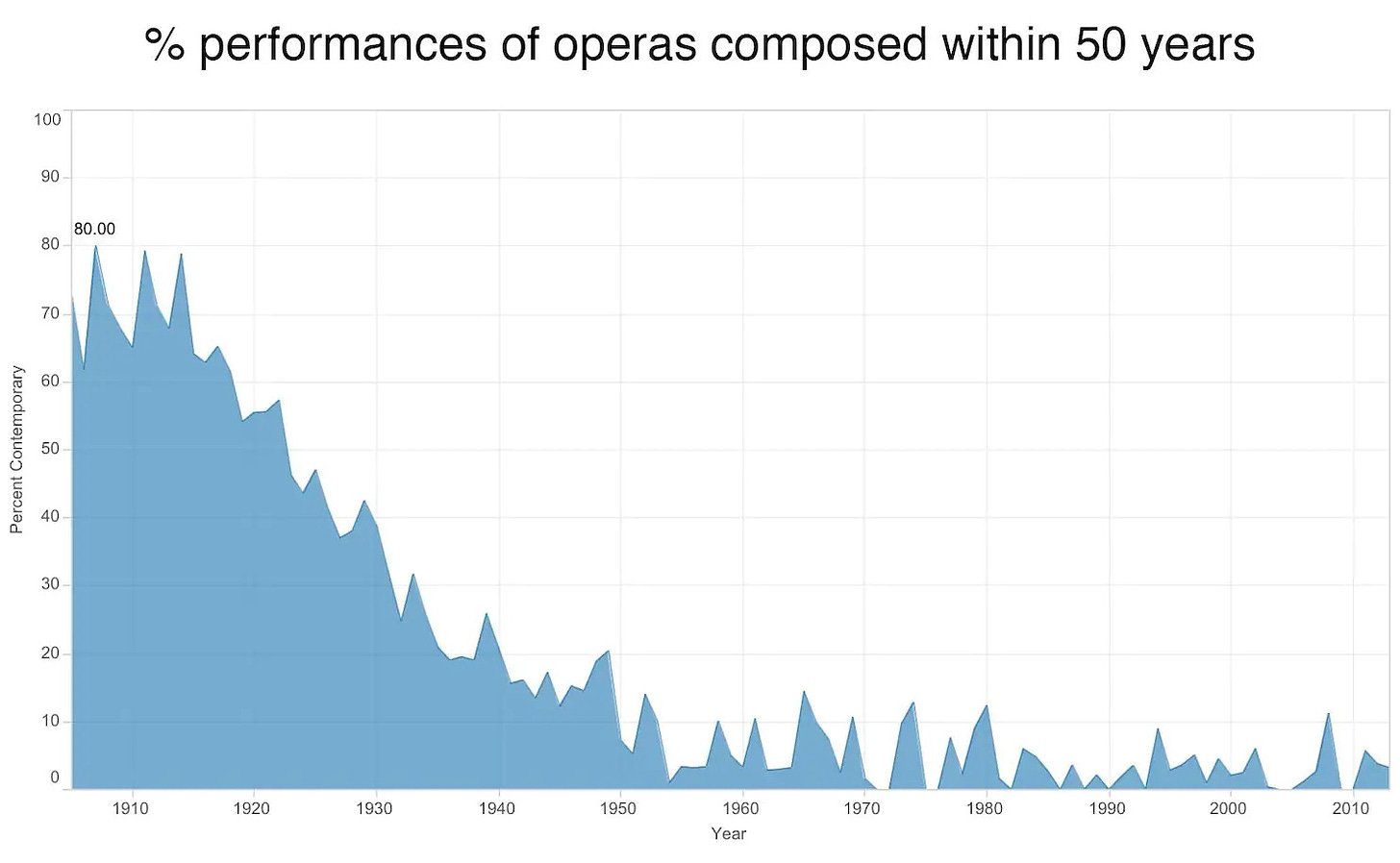

And most of the ticket-buying public knows it. Take opera, for example. An article by Christopher Ingraham purports to show that “Opera is dead, in one chart” (The Washington Post, October 31, 2014). Here’s the chart and Ingraham’s interpretation of it:

The chart shows that opera ceased to exist as a contemporary art form roughly around 1970. It’s from a blog post by composer and programmer Suby Raman, who scraped the Met’s public database of performances going back to the 19th century. As Raman notes, 50 years is an insanely low bar for measuring the “contemporary” – in pop music terms, it would be like considering The Beatles’ I Wanna Hold Your Hand as cutting-edge.

Back at the beginning of the 20th century, anywhere from 60 to 80 percent of Met performances were of operas composed in some time in the 50 years prior. But since 1980, the share of contemporary performances has surpassed 10 percent only once.

Opera, as a genre, is essentially frozen in amber – Raman found that the median year of composition of pieces performed at the Met has always been right around 1870. In other words, the Met is essentially performing the exact same pieces now that it was 100 years ago….

Contrary to Ingraham, opera isn’t dead; for example, there are more than 220 active opera companies in the U.S. It’s just that there’s little demand for operatic works written after the late 1800s. Why? Because most opera-lovers don’t want to hear the strident, discordant, unmelodic trash that came later. Giacomo Puccini, who wrote melodic crowd-pleasers until his death in 1924, is an exception that proves the rule.

Language is in the same parlous state as the arts. Written and spoken English improved steadily as Americans became more educated — and as long as that education included courses which prescribed rules of grammar and usage. By “improved” I mean that communication became easier and more effective; specifically:

- A larger fraction of Americans followed the same rules in formal communications (e.g., speeches, business documents, newspapers, magazines, and books,).

- Movies and radio and TV shows also tended to follow those rules, thereby reaching vast numbers of Americans who did little or no serious reading.

- There was a “trickle down” effect on Americans’ written and spoken discourse, especially where it involved mere acquaintances or strangers. Standard American English became a kind of lingua franca, which enabled the speaker or writer to be understood and taken seriously.

I call that progress.

There is, however, an (unfortunately) influential attitude toward language known as descriptivism. It is distinct from (and often opposed to) rule-setting (prescriptivism). Consider this passage from the first chapter of an online text:

Prescriptive grammar is based on the idea that there is a single right way to do things. When there is more than one way of saying something, prescriptive grammar is generally concerned with declaring one (and only one) of the variants to be correct. The favored variant is usually justified as being better (whether more logical, more euphonious, or more desirable on some other grounds) than the deprecated variant. In the same situation of linguistic variability, descriptive grammar is content simply to document the variants – without passing judgment on them.

This misrepresents the role of prescriptive grammar. It’s widely understood that there’s more than one way of expressing an idea and more than one way in which the idea can be made understandable to others. The rules of prescriptive grammar, when followed, improve understanding, in two ways. First, by avoiding utterances that would be incomprehensible or, at least, very hard to understand. Second, by ensuring that utterances aren’t simply ignored or rejected out of hand because their form indicates that the writer or speaker is either ill-educated or stupid.

What, then, is the role of descriptive grammar? The authors offer this:

[R]ules of descriptive grammar have the status of scientific observations, and they are intended as insightful generalizations about the way that speakers use language in fact, rather than about the way that they ought to use it. Descriptive rules are more general and more fundamental than prescriptive rules in the sense that all sentences of a language are formed in accordance with them, not just a more or less arbitrary subset of shibboleth sentences. A useful way to think about the descriptive rules of a language … is that they produce, or generate, all the sentences of a language. The prescriptive rules can then be thought of as filtering out some (relatively minute) portion of the entire output of the descriptive rules as socially unacceptable.

Let’s consider the assertion that descriptive rules produce all the sentences of a language. What does that mean? It seems to mean the actual rules of a language can be inferred by examining sentences uttered or written by users of the language. But which users? Native users? Adults? Adults who have graduated from high-school? Users with IQs of at least 100?

Pushing on, let’s take a closer look at descriptive rules and their utility. The authors say that

we adopt a resolutely descriptive perspective concerning language. In particular, when linguists say that a sentence is grammatical, we don’t mean that it is correct from a prescriptive point of view, but rather that it conforms to descriptive rules….

The descriptive rules amount to this: They conform to practices that a speakers and writers actually use in an attempt to convey ideas, whether or not the practices state the ideas clearly and concisely. Thus the authors approve of these sentences because they’re of a type that might well occur in colloquial speech:

- Over there is the guy who I went to the party with.

- Over there is the guy with whom I went to the party.

- (Both are clumsy ways of saying “I went to the party with that person.”)

- Bill and me went to the store.

(Alternatively: “Bill and I went to the store.” “Bill went to the store with me.” “I went to the store with Bill.” Aha! Three ways to say it correctly, not just one way.)

But the authors label the following sentences as ungrammatical because they don’t comport with the colloquial speech:

- Over there is guy the who I went to party the with.

- Over there is the who I went to the party with guy.

- Bill and me the store to went.

In other words, the authors accept as grammatical anything that a speaker or writer is likely to say, according to the “rules” that can be inferred from colloquial speech and writing. It follows that whatever is is right, even “Bill and me to the store went” or “Went to the store Bill and me”, which aren’t far-fetched variations on “Bill and me went to the store.” (Yoda-isms they read like.) They’re understandable, but only with effort. And further evolution would obliterate their meaning.

The fact is that the authors of the online text — like descriptivists generally — don’t follow their own anarchistic prescription. Follett puts it this way in Modern American Usage:

It is … one of the striking features of the libertarian position [with respect to language] that it preaches an unbuttoned grammar in a prose style that is fashioned with the utmost grammatical rigor. H.L. Mencken’s two thousand pages on the vagaries of the American language are written in the fastidious syntax of a precisian. If we go by what these men do instead of by what they say, we conclude that they all believe in conventional grammar, practice it against their own preaching, and continue to cultivate the elegance they despise in theory….

[T]he artist and the user of language for practical ends share an obligation to preserve against confusion and dissipation the powers that over the centuries the mother tongue has acquired. It is a duty to maintain the continuity of speech that makes the thought of our ancestors easily understood, to conquer Babel every day against the illiterate and the heedless, and to resist the pernicious and lulling dogma that in language … whatever is is right and doing nothing is for the best. [Pp. 30-31]

Follett also states the true purpose of prescriptivism, which isn’t to prescribe rules for their own sake:

[This book] accept[s] the long-established conventions of prescriptive grammar … on the theory that freedom from confusion is more desirable than freedom from rule…. [P. 243]

E.B. White says it more colorfully in his introduction to The Elements of Style. Writing about William Strunk Jr., author of the original version of the book, White says:

All through The Elements of Style one finds evidence of the author’s deep sympathy for the reader. Will felt that the reader was in serious trouble most of the time, a man floundering in a swamp, and that it was the duty of anyone attempting to write English to drain this swamp quickly and get his man up on dry ground, or at least throw him a rope. In revising the text, I have tried to hold steadily in mind this belief of his, this concern for the bewildered reader. [P. xvi, third edition]

Descriptivists would let readers founder in the swamp of incomprehensibility. If descriptivists had their way — or what they claim to be their way — American English would, like the arts, recede into formless primitivism.

Eternal vigilance about language is the price of comprehensibility.

B. Illegitimi Non Carborundum Lingo

The vigilant are sorely tried these days. What follows are several restrained rants about some practices that should be resisted and repudiated.

1. Eliminate filler words.

When I was a child, most parents and all teachers told children to desist from saying “uh” between words. “Uh” was then the filler word favored by children, adolescents, and even adults. The resort to “uh” meant that the speaker was stalling because he had opened his mouth without having given enough thought to what he meant to say.

Next came “you know”. It has been displaced, in the main, by “like”, where it hasn’t been joined to “like” in the formation “like, you know”.

The need of a filler word (or phrase) seems ineradicable. Too many people insist on opening their mouths before thinking about what they’re about to say. Given that, I urge Americans in need of a filler word to use “uh” and eschew “like” and “like, you know”. “Uh” is far less distracting and irritating than the rat-a-tat of “like-like-like-like”.

Of course, it may be impossible to return to “uh”. Its brevity may not give the users of “like” enough time to organize their TV-smart-phone-video-game-addled brains and deliver coherent speech.

In any event, speech influences writing. Sloppy speech begets sloppy writing, as I know too well. I have spent the past 60 years of my life trying to undo habits of speech acquired in my childhood and adolescence — habits that still creep into my writing if I drop my guard.

2. Don’t abuse words.

How am I supposed to know what you mean if you abuse perfectly good words? Here I discuss four prominent examples of abuse.

Anniversary

Too many times in recent years I’ve heard or read something like this: “Sally and me are celebrating our one-year anniversary.” The “and me” is bad enough; “one-year anniversary” (or any variation of it) is truly egregious.

The word “anniversary” means “the annually recurring date of a past event”. To write or say “x-year anniversary” is redundant as well as graceless. Just write or say “first anniversary”, “two-hundred fiftieth anniversary”, etc., as befits the occasion.

To write or say “x-month anniversary” is nonsensical. Something that happened less than a year ago can’t have an anniversary. What is meant is that such-and-such happened “x” months ago. Just say it.

Data

A person who writes or says “data is” is at best an ignoramus and at worst a Philistine.

Language, above all else, should be used to make one’s thoughts clear to others. The pairing of a plural noun and a singular verb form is distracting, if not confusing. Even though datum is seldom used by Americans, it remains the singular form of data, which is the plural form. Data, therefore, never “is”; data always “are”.

H.W. Fowler says:

Latin plurals sometimes become singular English words (e.g., agenda, stamina) and data is often so treated in U.S.; in Britain this is still considered a solecism… [A Dictionary of Modern English Usage, p.119, second edition]

But Follett’s Modern American Usage is better on the subject:

Those who treat data as a singular doubtless think of it as a generic noun, comparable to knowledge or information [a generous interpretation]…. The rationale of agenda as a singular is its use to mean a collective program of action, rather than separate items to be acted on. But there is as yet no obligation to change the number of data under the influence of error mixed with innovation. [Pp. 130-131]

Hopefully and Its Brethren

Mark Liberman of Language Logdiscusses

the AP Style Guide’s decision to allow the use of hopefully as a sentence adverb, announced on Twitter at 6:22 a.m. on 17 April 2012:

Hopefully, you will appreciate this style update, announced at #aces2012. We now support the modern usage of hopefully: it’s hoped, we hope.

Liberman, who is a descriptivist, defends AP’s egregious decision. His defense consists mainly of citing noted writers who have used “hopefully” where they meant “it is to be hoped”. I suppose that if those same noted writers had chosen to endanger others by driving on the wrong side of the road, Liberman would praise them for their “enlightened” approach to driving.

Geoff Nunberg also defends “hopefully“ in “The Word ‘Hopefully’ Is Here to Stay, Hopefully”, which appears at npr.org. Numberg (or the headline writer) may be right in saying that “hopefully” is here to stay. But that does not excuse the widespread use of the word in ways that are imprecise and meaningless.

The crux of Nunberg’s defense is that “hopefully” conveys a nuance that “language snobs” (e.g., me) are unable to grasp:

Some critics object that [“hopefully” is] a free-floating modifier (a Flying Dutchman adverb, James Kirkpatrick called it) that isn’t attached to the verb of the sentence but rather describes the speaker’s attitude. But floating modifiers are mother’s milk to English grammar — nobody objects to using “sadly,” “mercifully,” “thankfully” or “frankly” in exactly the same way.

Or people complain that “hopefully” doesn’t specifically indicate who’s doing the hoping. But neither does “It is to be hoped that,” which is the phrase that critics like Wilson Follett offer as a “natural” substitute. That’s what usage fetishism can drive you to — you cross out an adverb and replace it with a six-word impersonal passive construction, and you tell yourself you’ve improved your writing.

But the real problem with these objections is their tone-deafness. People get so worked up about the word that they can’t hear what it’s really saying. The fact is that “I hope that” doesn’t mean the same thing that “hopefully” does. The first just expresses a desire; the second makes a hopeful prediction. I’m comfortable saying, “I hope I survive to 105″ — it isn’t likely, but hey, you never know. But it would be pushing my luck to say, “Hopefully, I’ll survive to 105,” since that suggests it might actually be in the cards.

Floating modifiers may be common in English, but that does not excuse them. Given Numberg’s evident attachment to them, I am unsurprised by his assertion that “nobody objects to using ‘sadly,’ ‘mercifully,’ ‘thankfully’ or ‘frankly’ in exactly the same way.”

Nobody, Mr. Nunberg? Hardly. Anyone who cares about clarity and precision in the expression of ideas will object to such usages. A good editor would rewrite any sentence that begins with a free-floating modifier — no matter which one of them it is.

Nunberg’s defense against such rewriting is that Wilson Follett offers “It is to be hoped that” as a cumbersome, wordy substitute for “hopefully”. I assume that Nunberg refers to Follett’s discussion of “hopefully” in Modern American Usage. If so, Nunberg once again proves himself an adherent of imprecision, for this is what Follett actually says about “hopefully”:

The German language is blessed with an adverb, hoffentlich, that affirms the desirability of an occurrence that may or may not come to pass. It is generally to be translated by some such periphrasis as it is to be hoped that; but hack translators and persons more at home in German than in English persistently render it as hopefully. Now, hopefully and hopeful can indeed apply to either persons or affairs. A man in difficulty is hopeful of the outcome, or a situation looks hopeful; we face the future hopefully, or events develop hopefully. What hopefully refuses to convey in idiomatic English is the desirability of the hoped-for event. College, we read, is a place for the development of habits of inquiry, the acquisition of knowledge and, hopefully, the establishment of foundations of wisdom. Such a hopefully is un-English and eccentric; it is to be hoped is the natural way to express what is meant. The underlying mentality is the same—and, hopefully, the prescription for cure is the same (let us hope) / With its enlarged circulation–and hopefully also increased readership–[a periodical] will seek to … (we hope) / Party leaders had looked confidently to Senator L. to win . . . by a wide margin and thus, hopefully, to lead the way to victory for. . . the Presidential ticket (they hoped) / Unfortunately–or hopefully, as you prefer it–it is none too soon to formulate the problems as swiftly as we can foresee them. In the last example, hopefully needs replacing by one of the true antonyms of unfortunately–e.g. providentially.

The special badness of hopefully is not alone that it strains the sense of -ly to the breaking point, but that appeals to speakers and writers who do not think about what they are saying and pick up VOGUE WORDS [another entry in Modern American Usage] by reflex action. This peculiar charm of hopefully accounts for its tiresome frequency. How readily the rotten apple will corrupt the barrel is seen in the similar use of transferred meaning in other adverbs denoting an attitude of mind. For example: Sorrowfully (regrettably), the officials charged with wording such propositions for ballot presentation don’t say it that way / the “suicide needle” which–thankfully–he didn’t see fit to use (we are thankful to say). Adverbs so used lack point of view; they fail to tell us who does the hoping, the sorrowing, or the being thankful. Writers who feel the insistent need of an English equivalent for hoffentlich might try to popularize hopingly, but must attach it to a subject capable of hoping. [Op. cit., pp. 178-179]

Follett, contrary to Nunberg’s assertion, does not offer “It is to be hoped that” as a substitute for “hopefully”, which would “cross out an adverb and replace it with a six-word impersonal passive construction”. Follett gives “it is to be hoped for” as the sense of “hopefully”. But, as the preceding quotation attests, Follett is able to replace “hopefully” (where it is misused) with a few short words that take no longer to write or say than “hopefully”, and which convey the writer’s or speaker’s intended meaning more clearly. And if it does take a few extra words to say something clearly, why begrudge those words?

What about the other floating modifiers — such as “sadly”, “mercifully”, “thankfully”, and “frankly” — which Nunberg defends with much passion and no logic? Follett addresses those others in the third paragraph quoted above, but he does not dispose of them properly. For example, I would not simply substitute “regrettably” for “sorrowfully”; neither is adequate. What is wanted is something like this: “The officials who write propositions for ballots should not have said … , which is misleading (vague/ambiguous).” More words? Yes, but so what? (See above.)

In any event, a writer or speaker who is serious about expressing himself clearly to an audience will never say things like “Sadly (regrettably), the old man died” when he means either “I am (we are/they are/everyone who knew him is) saddened by (regrets) the old man’s dying”, or (less probably) “The old man grew sad as he died” or “The old man regretted dying.” I leave “mercifully”, “thankfully”, “frankly”, and the rest of the overused “-ly” words as an exercise for the reader.

The aims of a writer or speaker ought to be clarity and precision, not a stubborn, pseudo-logical insistence on using a word or phrase merely because it is in vogue or (more likely) because it irritates so-called language snobs. I doubt that even the pseudo-logical “language slobs” of Nunberg’s ilk condone “like” and “you know” as interjections. But by Nunberg’s “logic” those interjections should be condoned — nay, encouraged — because “everyone” knows what someone who uses them is “really saying”, namely, “I am too stupid or lazy to express myself clearly and precisely.”

Literally

This is from Dana Coleman’s article “According to the Dictionary, ‘Literally’ Also Now Means ‘Figuratively’”, (Salon, August 22, 2013):

Literally, of course, means something that is actually true: “Literally every pair of shoes I own was ruined when my apartment flooded.”

When we use words not in their normal literal meaning but in a way that makes a description more impressive or interesting, the correct word, of course, is “figuratively”.

But people increasingly use “literally” to give extreme emphasis to a statement that cannot be true, as in: “My head literally exploded when I read Merriam-Webster, among others, is now sanctioning the use of literally to mean just the opposite.”

Indeed, Ragan’s PR Daily reported last week that Webster, Macmillan Dictionary and Google have added this latter informal use of “literally” as part of the word’s official definition. The Cambridge Dictionary has also jumped on board….

Webster’s first definition of literally is, “in a literal sense or matter; actually”. Its second definition is, “in effect; virtually”. In addressing this seeming contradiction, its authors comment:

“Since some people take sense 2 to be the opposition of sense 1, it has been frequently criticized as a misuse. Instead, the use is pure hyperbole intended to gain emphasis, but it often appears in contexts where no additional emphasis is necessary.”…

The problem is that a lot of people use “literally” when they mean “figuratively” because they don’t know better. It’s literally* incomprehensible to me that the editors of dictionaries would suborn linguistic anarchy. Hopefully,** they’ll rethink their rashness.

_________

* “Literally” is used correctly, though it’s superfluous here.

** “Hopefully” is used incorrectly, but in the spirit of the times.

3. Punctuate properly.

I can’t compete with Lynne Truss’s Eats, Shoots & Leaves, so I won’t try. Just read it and heed it.

But I must address the use of the hyphen in compound adjectives, and the serial comma.

Regarding the hyphen, David Bernstein of The Volokh Conspiracy writes:

I frequently have disputes with law review editors over the use of dashes. Unlike co-conspirator Eugene, I’m not a grammatical expert, or even someone who has much of an interest in the subject.

But I do feel strongly that I shouldn’t use a dash between words that constitute a phrase, as in “hired gun problem”, “forensic science system”, or “toxic tort litigation.” Law review editors seem to want to generally want to change these to “hired-gun problem”, “forensic-science system”, and “toxic-tort litigation.” My view is that “hired” doesn’t modify “gun”; rather “hired gun” is a self-contained phrase. The same with “forensic science” and “toxic tort.”

Most of the commenters are right to advise Bernstein that the “dashes” — he means hyphens — are necessary. Why? To avoid confusion as to what is modifying the noun “problem”.

In “hired gun”, for example, “hired” (adjective) modifies “gun” (noun) to convey the idea of a bodyguard or paid assassin. But in “hired-gun problem”, “hired-gun” is a compound adjective which requires both of its parts to modify “problem”. It’s not a “hired problem” or a “gun problem”, it’s a “hired-gun problem”. The function of the hyphen is to indicate that “hired” and “gun”, taken separately, are meaningless as modifiers of “problem”, that is, to ensure that the meaning of the adjective-noun phrase is not misread.

A hyphen isn’t always necessary in such instances. But the consistent use of the hyphen in such instances avoids confusion and the possibility of misinterpretation.

The consistent use of the hyphen to form a compound adjective has a counterpart in the consistent use of the serial comma, which is the comma that precedes the last item in a list of three or more items (e.g., the red, white, and blue). Newspapers (among other sinners) eschew the serial comma for reasons too arcane to pursue here. Thoughtful counselors advise its use. (See, for example, Modern American Usage at pp. 422-423.) Why? Because the serial comma, like the hyphen in a compound adjective, averts ambiguity. It isn’t always necessary, but if it’s used consistently, ambiguity can be avoided. (Here’s a great example, from the Wikipedia article linked to in the first sentence of this paragraph: “To my parents, Ayn Rand and God”. The writer means, of course, “To my parents, Ayn Rand, and God”.)

A little punctuation goes a long way.

Addendum

I have reverted to the British style of punctuating in-line quotations, which I followed 45 years ago when I published a weekly newspaper. The British style is to enclose within quotation marks only (a) the punctuation that appears in quoted text or (b) the title of a work (e.g., a blog post) that is usually placed within quotation marks.

I have reverted because of the confusion and unsightliness caused by the American style. It calls for the placement of periods and commas within quotation marks, even if the periods and commas don’t occur in the quoted material or title. Also, if there is a question mark at the end of quoted material, it replaces the comma or period that might otherwise be placed there.

If I had continued to follow American style, I would have referred to a series of blog posts in this way:

… “A New (Cold) Civil War or Secession?” “The Culture War,” “Polarization and De-facto Partition,” and “Civil War?“

What a hodge-podge. There’s no comma between the first two entries, and the sentence ends with an inappropriate question mark. With two titles ending in question marks, there was no way for me to avoid a series in which a comma is lacking. I could have avoided the sentence-ending question mark by recasting the list, but the items are listed chronologically, which is how they should be read.

I solved these problems easily by reverting to the British style:

… “A New (Cold) Civil War or Secession?”, “The Culture War“, “Polarization and De-facto Partition“, and “Civil War?“.

This not only eliminates the hodge-podge, but is also more logical and accurate. All items are separated by commas, commas aren’t displaced by question marks, and the declarative sentence ends with a period instead of a question mark.

4. Why “‘s” matters, or how to avoid ambiguity in possessives.

Most newspapers and magazines follow the convention of forming the possessive of a word ending in “s” by putting an apostrophe after the “s”; for example:

- Dallas’ (for Dallas’s)

- Texas’ (for Texas’s)

- Jesus’ (for Jesus’s)

This may work on a page or screen, but it can cause ambiguity if carried over into speech*. (If I were the kind of writer who condescends to his readers, I would at this point insert the following “trigger warning”: I am about to take liberties with the name of Jesus and the New Testament, about which I will write as if it were a contemporary document. Read no further if you are easily offended.)

What sounds like “Jesus walks on water” could mean just what it sounds like: a statement about a feat of which Jesus is capable or is performing. But if Jesus walks on the water more than once, it could refer to his plural perambulations: “Jesus’ walks on water”**, as it would appear in a newspaper.

The simplest and best way to avoid the ambiguity is to insist on “Jesus’s walks on water”** for the possessive case, and to inculcate the practice of saying it as it reads. How else can the ambiguity be avoided, in the likely event that the foregoing advice will be ignored?

If what is meant is “Jesus walks on water”, one could say “Jesus can [is able to] walk on water” or “Jesus is walking on water”, according to the situation.

If what is meant is that Jesus walks on water more than once, “Jesus’s walks on water” is unambiguous (assuming, of course, that one’s listeners have an inkling about the standard formation of a singular possessive). There’s no need to work around it, as there is in the non-possessive case. But if you insist on avoiding the “‘s” formation, you can write or say “the water-walks of Jesus”.

I now take it to the next level.

What if there’s more than one Jesus who walks on water? Well, if they all can walk on water and the idea is to say so, it’s “the Jesuses walk on water”. And if they all walk on water and the idea is to refer to those outings as the outings of them all, it’s “the water-walks of the Jesuses”.

Why? Because the standard formation of the plural possessive of Jesus is Jesuses’. Jesusues’s would be too hard to say or comprehend. But Jesuses’ sounds the same as Jesuses, and must therefore be avoided in speech, and in writing intended to be read aloud. Thus “the water walks of the Jesuses” instead of “the Jesuses’ walks on water”, which is ambiguous to a listener.

__________

* A good writer will think about the effect of his writing if it is read aloud.

** “Jesus’ walks on water” and “Jesus’s walks on water” misuse the possessive case, though it’s a standard kind misuse that is too deeply entrenched to be eradicated. Strictly speaking, Jesus doesn’t own walks on water, he does them. The alternative construction, “the water-walks of Jesus”, is better; “the water-walks by Jesus” is best.

5. Stand fast against political correctness.

As a result of political correctness, some words and phrases have gone out of favor. needlessly. Others are cluttering the language, needlessly. Political correctness manifests itself in euphemisms, verboten words, and what I call gender preciousness.

Euphemisms

These are much-favored by persons of the left, who seem unable to have an aversion to reality. Thus, for example:

- “Crippled” became “handicapped”, which became “disabled” and then “differently-abled” or “mobility-challenged”.

- “Stupid” and “slow” became “learning disabled”, which became “special needs” (a euphemistic category that houses more than the stupid).

- “Poor” became “underprivileged”, which became “economically disadvantaged”, which became “entitled” (to other people’s money).

- “Colored persons” became “Negroes”, who became “blacks”, “Blacks”, and “African-Americans”. They are now often called “persons of color”. That looks like a variant of “colored persons”, but it also refers to a segment of humanity that includes almost everyone but white persons who are descended solely from long-time inhabitants the British Isles and continental Europe.

How these linguistic contortions have helped the crippled, stupid, poor, and colored is a mystery to me. Tact is admirable, but euphemisms aren’t tactful. They’re insulting because they’re condescending.

Verboten Words

The list of such words is long and growing longer. Words become verboten for the same reason that euphemisms arise: to avoid giving offense, even where offense wouldn’t or shouldn’t be taken.

David Bernstein, writing at TCS Daily several ago, recounted some tales about political correctness (source no longer available online). This one struck close to home:

One especially merit-less [hostile work environment] claim that led to a six-figure verdict involved Allen Fruge, a white Department of Energy employee based in Texas. Fruge unwittingly spawned a harassment suit when he followed up a southeast Texas training session with a bit of self-deprecating humor. He sent several of his colleagues who had attended the session with him gag certificates anointing each of them as an honorary Coon Ass — usually spelled coonass — a mildly derogatory slang term for a Cajun. The certificate stated that [y]ou are to sing, dance, and tell jokes and eat boudin, cracklins, gumbo, crawfish etouffe and just about anything else. The joke stemmed from the fact that southeast Texas, the training session location, has a large Cajun population, including Fruge himself.

An African American recipient of the certificate, Sherry Reid, chief of the Nuclear and Fossil Branch of the DOE in Washington, D.C., apparently missed the joke and complained to her supervisors that Fruge had called her a coon. Fruge sent Reid a formal (and humble) letter of apology for the inadvertent offense, and explained what Coon Ass actually meant. Reid nevertheless remained convinced that Coon Ass was a racial pejorative, and demanded that Fruge be fired. DOE supervisors declined to fire Fruge, but they did send him to diversity training. They also reminded Reid that the certificate had been meant as a joke, that Fruge had meant no offense, that Coon Ass was slang for Cajun, and that Fruge sent the certificates to people of various races and ethnicities, so he clearly was not targeting African Americans. Reid nevertheless sued the DOE, claiming that she had been subjected to a racial epithet that had created a hostile environment, a situation made worse by the DOEs failure to fire Fruge.

Reid’s case was seemingly frivolous. The linguistics expert her attorney hired was unable to present evidence that Coon Ass meant anything but Cajun, or that the phrase had racist origins, and Reid presented no evidence that Fruge had any discriminatory intent when he sent the certificate to her. Moreover, even if Coon Ass had been a racial epithet, a single instance of being given a joke certificate, even one containing a racial epithet, by a non-supervisory colleague who works 1,200 miles away does not seem to remotely satisfy the legal requirement that harassment must be severe and pervasive for it to create hostile environment liability. Nevertheless, a federal district court allowed the case to go to trial, and the jury awarded Reid $120,000, plus another $100,000 in attorneys fees. The DOE settled the case before its appeal could be heard for a sum very close to the jury award.

I had a similar though less costly experience some years ago, when I was chief financial and administrative officer of a defense think-tank. In the course of discussing the company’s budget during meeting with employees from across the company, I uttered “niggardly” (meaning stingy or penny-pinching). The next day a fellow vice president informed me that some of the black employees from her division had been offended by “niggardly”. I suggested that she give her employees remedial training in English vocabulary. That should have been the verdict in the Reid case.

Gender Preciousness

It has become fashionable for academicians and pseudo-serious writers to use “she” where “he” long served as the generic (and sexless) reference to a singular third person. Here is an especially grating passage from an by Oliver Cussen:

What is a historian of ideas to do? A pessimist would say she is faced with two options. She could continue to research the Enlightenment on its own terms, and wait for those who fight over its legacy—who are somehow confident in their definitions of what “it” was—to take notice. Or, as [Jonathan] Israel has done, she could pick a side, and mobilise an immense archive for the cause of liberal modernity or for the cause of its enemies. In other words, she could join Moses Herzog, with his letters that never get read and his questions that never get answered, or she could join Sandor Himmelstein and the loud, ignorant bastards. [“The Trouble with the Enlightenment”, Prospect, May 5, 2013]

I don’t know about you, but I’m distracted by the use of the generic “she”, especially by a male. First, it’s not the norm (or wasn’t the norm until the thought police made it so). Thus my first reaction to reading it in place of “he” is to wonder who this “she” is; whereas, the function of “he” as a stand-in for anyone (regardless of gender) was always well understood. Second, the usage is so obviously meant to mark the writer as “sensitive” and “right thinking” that it calls into question his sincerity and objectivity. I call this in evidence of my position:

The use of the traditional inclusive generic pronoun “he” is a decision of language, not of gender justice. There are only six alternatives. (1) We could use the grammatically misleading and numerically incorrect “they.” But when we say “one baby was healthier than the others because they didn’t drink that milk,” we do not know whether the antecedent of “they” is “one” or “others,” so we don’t know whether to give or take away the milk. Such language codes could be dangerous to baby’s health. (2) Another alternative is the politically intrusive “in-your-face” generic “she,” which I would probably use if I were an angry, politically intrusive, in-your-face woman, but I am not any of those things. (3) Changing “he” to “he or she” refutes itself in such comically clumsy and ugly revisions as the following: “What does it profit a man or woman if he or she gains the whole world but loses his or her own soul? Or what shall a man or woman give in exchange for his or her soul?” The answer is: he or she will give up his or her linguistic sanity. (4) We could also be both intrusive and clumsy by saying “she or he.” (5) Or we could use the neuter “it,” which is both dehumanizing and inaccurate. (6) Or we could combine all the linguistic garbage together and use “she or he or it,” which, abbreviated, would sound like “sh . . . it.” I believe in the equal intelligence and value of women, but not in the intelligence or value of “political correctness,” linguistic ugliness, grammatical inaccuracy, conceptual confusion, or dehumanizing pronouns. [Peter Kreeft, Socratic Logic, 3rd ed., p. 36, n. 1, as quoted by Bill Vallicella, Maverick Philosopher, May 9, 2015]

I could go on about the use of “he or she” in place of “he” or “she”. But it should be enough to call it what it is: verbal clutter. (As for “they”, “them”, and “their” in place of plural pronouns, see “Encounters with Pronouns” at Imlac’s Journal.)

Then there is “man”, which for ages was well understood (in the proper context) as referring to persons in general, not to male persons in particular. (“Mankind” merely adds a superfluous syllable.)

The short, serviceable “man” has been replaced, for the most part, by “humankind”. I am baffled by the need to replaced one syllable with three. I am baffled further by the persistence of “man” — a “sexist” term — in the three-syllable substitute. But it gets worse when writers strain to avoid the solo use of “man” by resorting to “human beings” and the “human species”. These are longer than “humankind”, and both retain the accursed “man”.

6. Don’t split infinitives.

Just don’t do it, regardless of the pleadings of descriptivists. Even Follett counsels the splitting of infinitives, when the occasion demands it. I part ways with Follett in this matter, and stand ready to be rebuked for it.

Consider the case of Eugene Volokh, a known grammatical relativist, who scoffs at “to increase dramatically” — as if “to dramatically increase” would be better. The meaning of “to increase dramatically” is clear. The only reason to write “to dramatically increase” would be to avoid the appearance of stuffiness; that is, to pander to the least cultivated of one’s readers.

Seeming unstuffy (i.e., without standards) is neither a necessary nor sufficient reason to split an infinitive. The rule about not splitting infinitives, like most other grammatical rules, serves the valid and useful purpose of preventing English from sliding yet further down the slippery slope of incomprehensibility than it has slid.

If an unsplit infinitive makes a clause or sentence seem awkward, the clause or sentence should be recast to avoid the awkwardness. Better that than make an exception that leads to further exceptions — and thence to Babel.

Modern English Usage counsels splitting an infinitive where recasting doesn’t seem to work:

We admit that separation of to from its infinitive is not in itself desirable, and we shall not gratuitously say either ‘to mortally wound’ or ‘to mortally be wounded’…. We maintain, however, that a real [split infinitive], though not desirable in itself, is preferable to either of two things, to real ambiguity, and to patent artificiality…. We will split infinitives sooner than be ambiguous or artificial; more than that, we will freely admit that sufficient recasting will get rid of any [split infinitive] without involving either of those faults, and yet reserve to ourselves the right of deciding in each case whether recasting is worth while. Let us take an example: ‘In these circumstances, the Commission … has been feeling its way to modifications intended to better equip successful candidates for careers in India and at the same time to meet reasonable Indian demands.’… What then of recasting? ‘intended to make successful candidates fitter for’ is the best we can do if the exact sense is to be kept… [P. 581]

Good try, but not good enough. This would do: “In these circumstances, the Commission … has been considering modifications that would better equip successful candidates for careers in India and at the same time meet reasonable Indian demands.”