This post supersedes “The American League’s Greatest Hitters: Part II” and “The American League’s Greatest Hitters.” Here, I build on “Bigger, Stronger, and Faster — but Not Quicker?” which assesses the long-term trend (or lack thereof) in batting skill.

Specifically, I derived ballpark factors (BF) for each AL team for each season from 1901 through 2016. For example, the fabled New York Yankees of 1927 hit 1.03 times as well at home as on the road. Given a schedule evenly divided between home and road games, this means that batting averages for the Yankees of 1927 were inflated by 1.015 relative to batting averages for players on other teams.

The BA of a 1927 Yankee — as adjusted by the method described in “Bigger, Stronger…” — should therefore be multiplied by a BF of 0.985 (1/1.015) to obtain that Yankee’s “true” BA for that season. (This is a player-season-specific adjustment, in addition the long-term trend adjustment applied in “Bigger, Stronger…,” which captures a gradual and general decline in home-park advantage.)

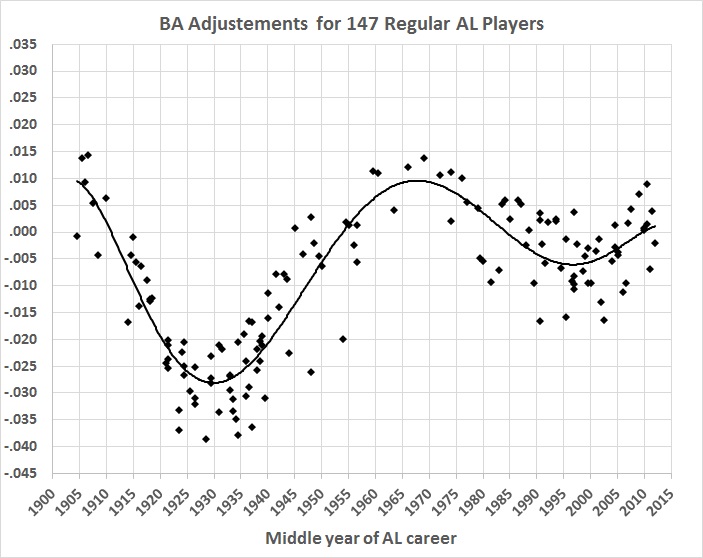

I made those adjustments for 147 players who had at least 5,000 plate appearances in the AL and an official batting average (BA) of at least .285 in those plate appearances. Here are the adjustments, plotted against the middle year of each player’s AL career:

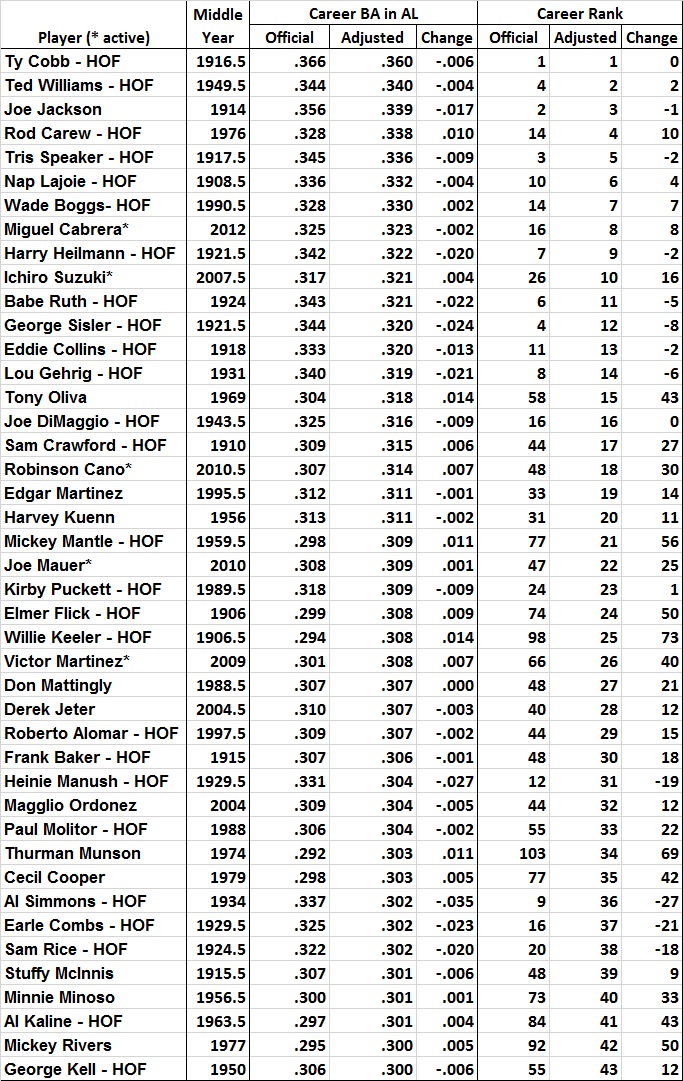

When all is said and done, there are only 43 qualifying players with an adjusted career BA of .300 or higher:

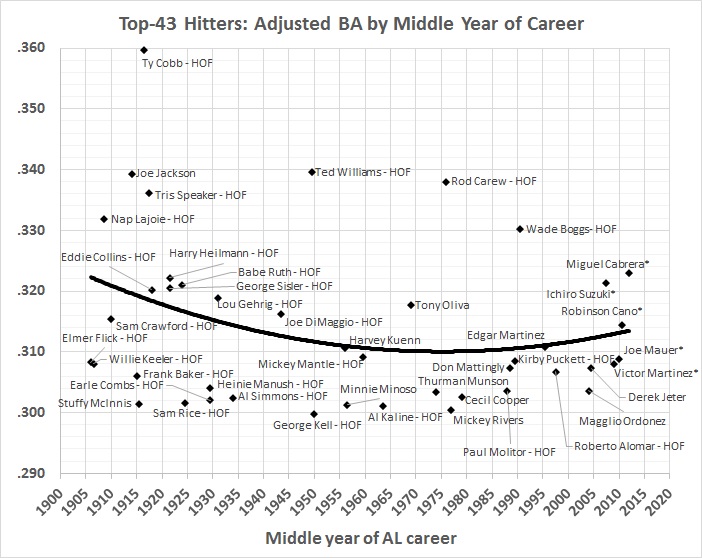

Here’s a graph of the relationship between adjusted career BA and middle-of-career year:

The curved line approximates the trend, which is downward until about the mid-1970s, then slightly upward. But there’s a lot of variation around that trend, and one player — Ty Cobb at .360 — clearly stands alone as the dominant AL hitter of all time.

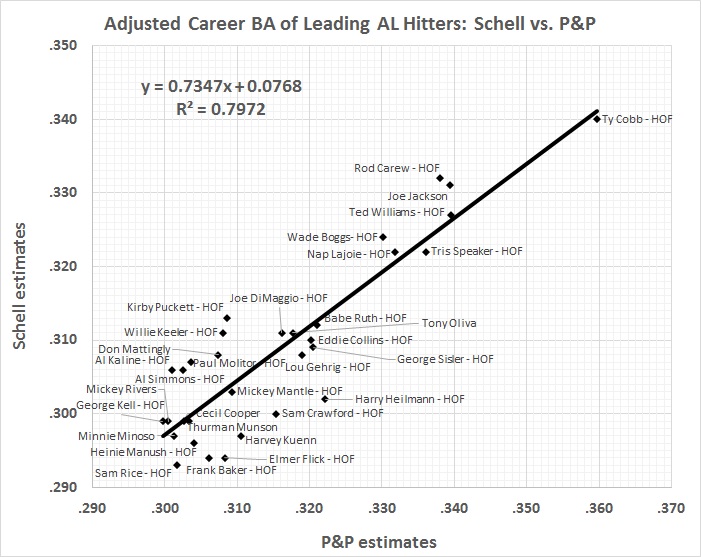

Michael Schell, in Baseball’s All-Time Best Hitters, ranks Cobb second behind Tony Gwynn, who spent his career (1982-2001) in the National League (NL), and much closer to Rod Carew, who played only in the AL (1967-1985). Schell’s adjusted BA for Cobb is .340, as opposed to .332 for Carew, an advantage of .008 for Cobb. I have Cobb at .360 and Carew at .338, an advantage of .022 for Cobb. The difference in our relative assessments of Cobb and Carew is typical; Schell’s analysis is biased (intentionally or not) toward recent and contemporary players and against players of the pre-World War II era.

Here’s how Schell’s adjusted BAs stack up against mine, for 32 leading hitters rated by both of us:

Schell’s bias toward recent and contemporary players is most evident in his standard-deviation (SD) adjustment:

In his book Full House, Stephen Jay Gould, an evolutionary biologist [who imported his ideological biases into his work]…. Gould imagines [emphasis added] that there is a “wall” of human ability. The best players at the turn of the [20th] century may have been close to the “wall,” many of their peers were not. Over time, progressively better hitters replace the weakest hitters. As a result, the best current hitters do not stand out as much from their peers.

Gould and I believe that the reduction in the standard deviation [of BA within a season] demonstrates that there has been an improvement in the overall quality of major league baseball today compared to nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century play. [pp. 94-95]

Thus Schell’s SD adjustment, which slashes the BA of the better hitters of the early part of the 20th century because the SDs of that era were higher than the SDs after World War II. The SD adjustment is seriously flawed for several reasons:

1. There may be a “wall” of human ability, or it may truly be imaginary. Even if there is such a wall, we have no idea how close Ty Cobb, Tony Gwynn, and other great hitters have been to it. That is to say, there’s no a priori reason (contra Schell’s implicit assumption) that Cobb couldn’t have been closer to the wall than Gwynn.

2. It can’t be assumed that reaction time — an important component of human ability, and certainly of hitting ability — has improved with time. In fact, there’s a plausible hypothesis to the contrary, which is stated in “Bigger, Stronger…” and examined there, albeit inconclusively.

3. Schell’s discussion of relative hitting skill implies, wrongly, that one player’s higher BA comes at the expense of other players. Not so. BA is a measure of the ability of a hitter to hit safely given the quality of pitching and other conditions (examined in detail in “Bigger, Stronger…”). It may be the case that weaker hitters were gradually replaced by better ones, but that doesn’t detract from the achievements of the better hitter, like Ty Cobb, who racked up his hits at the expense of opposing pitchers, not other batters.

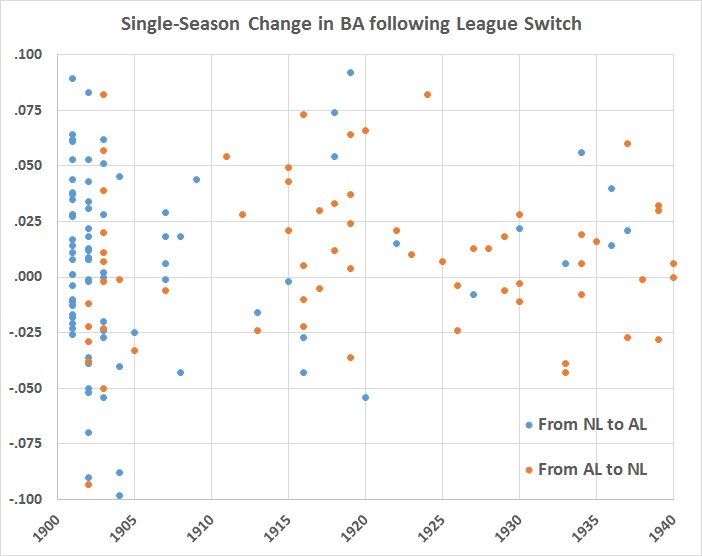

4. Schell asserts that early AL hitters were inferior to their NL counterparts, thus further justifying an SD adjustment that is especially punitive toward early AL hitters (e.g., Cobb). However, early AL hitters were demonstrably inferior to their NL counterparts only in the first two years of the AL’s existence, and well before the arrival of Cobb, Joe Jackson, Tris Speaker, Harry Heilmann, Babe Ruth, George Sisler, Lou Gehrig, and other AL greats of the pre-World War II era. Thus:

There seems to have been a bit of backsliding between 1905 and 1910, but the sample size for those years is too small to be meaningful. On the other hand, after 1910, hitters enjoyed no clear advantage by moving from NL to AL (or vice versa). The data for 1903 through 1940, taken altogether, suggest parity between the two leagues during that span.

One more bit of admittedly sketchy evidence:

- Cobb hit as well as Heilmann during Cobb’s final nine seasons as a regular player (1919-1927), which span includes the years in which the younger Heilmann won batting titles with average of .394, .403, 398, and .393.

- In that same span, Heilmann outhit Ruth, who was the same age as Heilmann.

- Ruth kept pace with the younger Gehrig during 1925-1932.

- In 1936-1938, Gehrig kept pace with the younger Joe DiMaggio, even though Gehrig’s BA dropped markedly in 1938 with the onset of the disease that was to kill him.

- The DiMaggio of 1938-1941 was the equal of the younger Ted Williams, even though the final year of the span saw Williams hit .406.

- Williams’s final three years as a regular, 1956-1958, overlapped some of the prime seasons of Mickey Mantle, who was 13 years Williams’s junior. Williams easily outhit Mantle during those years, and claimed two batting titles to Mantle’s one.

I see nothing in the preceding recitation to suggest that the great hitters of the years 1901-1940 were inferior to the great hitters of the post-WWII era. In fact, it points in the opposite direction. This might be taken as indirect confirmation of the hypothesis that reaction times have slowed. Or it might have something to do with the emergence of football and basketball as “serious” professional sports after WWII, an emergence that could well have led potentially great hitters to forsake baseball for another sport. Yet another possibility is that post-war prosperity and educational opportunities drew some potentially great hitters into non-athletic trades and professions. In other words, unlike Schell, I remain open to the possibility that there may have been a real, if slight, decline in hitting talent after WWII — a decline that was gradually reversed because of the eventual effectiveness of integration (especially of Latin American players) and the explosion of salaries with the onset of free agency.

Finally, in “Bigger, Stronger…” I account for the cross-temporal variation in BA by applying a general algorithm and then accounting for 14 discrete factors, including the ones applied by Schell. As a result, I practically eliminate the effects of the peculiar conditions that cause BA to be inflated in some eras relative to other eras. (See figure 7 of “Bigger, Stronger…” and the accompanying discussion.) Even after taking all of those factors into account, Cobb still stands out as the best AL hitter of all time — by a wide margin.

And given Cobb’s statistical dominance over his contemporaries in the NL, he still stands as the greatest hitter in the history of the major leagues.