Wherein the author finds money, banking, and credit to be good, not evil — as long as government keeps its hands off them.

MONEY LUBRICATES EXCHANGE

The important role of money as a lubricant of economic activity has been understood for a long time. Indeed, it must have been understood by the ancients who first devised money of one kind or another and used it to broaden the range of goods they could buy, sell, and use. For a less-than-ancient but venerable account of the role of money, I turn to Adam Smith:

When the division of labour has been once thoroughly established, it is but a very small part of a man’s wants which the produce of his own labour can supply. He supplies the far greater part of them by exchanging that surplus part of the produce of his own labour, which is over and above his own consumption, for such parts of the produce of other men’s labour as he has occasion for. Every man thus lives by exchanging, or becomes, in some measure, a merchant, and the society itself grows to be what is properly a commercial society.

But when the division of labour first began to take place, this power of exchanging must frequently have been very much clogged and embarrassed in its operations. One man, we shall suppose, has more of a certain commodity than he himself has occasion for, while another has less. The former, consequently, would be glad to dispose of; and the latter to purchase, a part of this superfluity. But if this latter should chance to have nothing that the former stands in need of, no exchange can be made between them. The butcher has more meat in his shop than he himself can consume, and the brewer and the baker would each of them be willing to purchase a part of it. But they have nothing to offer in exchange, except the different productions of their respective trades, and the butcher is already provided with all the bread and beer which he has immediate occasion for. No exchange can, in this case, be made between them. He cannot be their merchant, nor they his customers; and they are all of them thus mutually less serviceable to one another. In order to avoid the inconveniency of such situations, every prudent man in every period of society, after the first establishment of the division of labour, must naturally have endeavoured to manage his affairs in such a manner, as to have at all times by him, besides the peculiar produce of his own industry, a certain quantity of some one commodity or other, such as he imagined few people would be likely to refuse in exchange for the produce of their industry. Many different commodities, it is probable, were successively both thought of and employed for this purpose. In the rude ages of society, cattle are said to have been the common instrument of commerce; and, though they must have been a most inconvenient one, yet, in old times, we find things were frequently valued according to the number of cattle which had been given in exchange for them. The armour of Diomede, says Homer, cost only nine oxen; but that of Glaucus cost a hundred oxen. Salt is said to be the common instrument of commerce and exchanges in Abyssinia; a species of shells in some parts of the coast of India; dried cod at Newfoundland; tobacco in Virginia; sugar in some of our West India colonies; hides or dressed leather in some other countries; and there is at this day a village In Scotland, where it is not uncommon, I am told, for a workman to carry nails instead of money to the baker’s shop or the ale-house. (From An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, Chapter IV, “Of the Origin and the Use of Money.)

And so it went, until institutions of standing (banks, governments) began to issue money in standard, convenient forms, and which individuals would readily accept and use — within a particular region, principality, kingdom or nation, at least.

MONEY FACILITATES CREDIT, AND CREDIT CAN CREATE MONEY

Even in the absence of money, of course, there can be credit: the lending of products and services (i.e., economic goods or, simply, goods) for consumption or investment (i.e., capital formation: the creation of tools, facilities, and the like that can be used to produce goods in greater abundance, of higher quality, or of new kinds). Money facilitates credit because the borrower can use money to choose from a greater variety of consumption or investment goods; money, in effect, expands the time and space available to a buyer for the selection of goods.

Credit represents a kind of exchange, where the commodity involved is money, itself. The borrower and lender must agree to the terms of exchange, and the borrower (unless he is swayed by personal considerations and inclined to forgive a debt) will want some kind of assurance that his money will be repaid, at a rate of interest that he (the lender) is willing to accept, given the risk he assumes. Credit can underwrite the following activities:

- Consumption (meeting daily wants, from shelter to food and clothing to such “frills” as internet service, faddish toys and clothing, etc.)

- Purchases of durable consumer goods (e.g., automobiles, major appliances, and — for this purpose — residential dwellings)

- Capital formation to enable the production of more, better, and new kinds of goods, including production goods (e.g., farm equipment) as well as final goods (e.g., home computers).

For purposes of this exposition, I consider stock purchases to be a form of credit. The purchaser is not making a loan to be repaid on a schedule, but he is hoping to participate in the dividends and/or capital gains that will be generated by the business that issues the stock. In other words, to buy stock is really to grant an unsecured loan, in the expectation of a high return and with the knowledge that a lot of risk attaches to that expectation.

CREDIT AND THE MONEY-MULTIPLIER

What is the source of credit? That is, who — if anyone — is relinquishing a claim on resources in order to lend that claim to someone else? The obvious answer to the question is: the lender. But that is not the whole story, because of fractional-reserve banking (FR, to distinguish it from FRB, or Federal Reserve Board). FR has a long history, which predates the involvement of governments in banking. With FR, the cash held in reserve by a bank (or private lender) can be parlayed into loans (and thus money) having a face value many times that of the original lender’s reserve. In what follows, I will use examples that assume a “money multiplier” of 10; that is, a cash reserve of a given amount may be used to generate loans with a total face value equal to 10 times that of the reserve. (This article explains the process and the formula for determining potential value of the loans, and money, that can be generated by a given cash reserve.) It should be obvious that FR can be practiced only in a monetary economy; 100 head of cattle, for instance, cannot be parlayed into 1,000 head of cattle, because cattle cannot be created by the proverbial stroke of a pen, whereas money can — if others are willing to accept it.

Without FR, then, credit is created only when a lender forgoes spending that directly benefits him. For example, a lender who has just received $1,000 dollars for services rendered has a claim on the value of the goods he created by rendering those services. He could spend that $1,000 on some combination of consumption (e.g., groceries), durable consumer goods (e.g., a PC), or capital formation (e.g., new software for use in his tax-preparation business). Alternatively, he could lend the $1,000 (or some part of it) to someone else, who could put it to an analogous use or uses. Without FR, however, the growth of economic output depends (almost) entirely on the amount that individuals spend on capital formation or lend to others for capital formation. (I say “almost” because certain kinds of consumption and durable goods can also lead to future increases in output; for example, better nutrition and the use of refrigeration to prevent the contamination of food.)

THE MONEY-MULTIPLIER AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

FR can induce a higher rate of economic growth, if the following several conditions are satisfied:

- Lenders lend additional sums as a result of FR.

- The lending is not offset by reduced spending on the part of borrowers.

- The money that is borrowed indistinguishable from money that is already in use. That is to say, the borrowed money is treated like “real” money when borrowers put it into circulation by spending it.

- If it is “real” money, it give borrowers a claim on resources that they can exercise for the various reasons outlined above. But the resources that borrowers seek to command must be in addition to the resources that are already in use or that would have been in use in the absence of FR. (There may be some lags, as producers respond to additional spending with increases in output, and those lags will have an inflationary effect, but it may be offset by efficiencies of scale and/or greater productivity that results when some borrowers invest in capital formation.)

In summary: If enough additional money is created, if its expenditure calls forth enough additional production, and if enough that production flows into growth-inducing outlays, the result will be an acceleration of economic growth, relative to the growth that would have been attained without FR.

The biggest question mark attaches to the amount of lending that results when additional credit becomes available (potentially) because of FR. Potential increases in credit become actual increases only to the extent that particular lenders and prospective borrowers are willing to lend and borrow, respectively, at prevailing rates of interest, in light of their expectations of future economic conditions and the returns on particular uses of borrowed money. There is no mechanical or hydraulic process at work. (I am skirting a discussion of monetary policy, its shortcomings, and its merits relative to fiscal policy. For those who are interested in learning more about those matters, start here, here. here, and especially here.)

The essential point is that FR — like money — can foster the growth of economic activity. If there is nothing “artificial” about using money to expand economic activity — in the range of participants, their geographic scope, and the variety of goods they offer — there is nothing “artificial” using FR to further expand economic activity along the same lines.

THE “PROBLEM” WITH CREDIT-FUELED ECONOMIC EXPANSION

The perceptual problem is that people are unable to know just how much worse off they would be in the absence of credit. Credit-related downturns occur at a relatively high level of economic activity — a level that would not have been attained in the first place had it not been for credit.

When economic expansion is credit-based, it can be halted and reversed by a tightening of credit. In other words, credit-tightening supplements and magnifies the usual causes of economic retractions: natural disasters, epidemics, wars, technological shifts, overly ambitious capital and business formation, and so on. It is no coincidence that most of the economic downturns in American history have been initiated or deepened by the onset of a credit crisis.

Michael D. Bordo and Joseph G. Haubrich essay a rigorous historical and quantitative analysis of the relationship between credit crises and economic downturns in “Credit Crises, Money, and Contractions: A Historical View.” This is from the abstract:

Using a combination of historical narrative and econometric techniques, we identify major periods of credit distress from 1875 to 2007, examine the extent to which credit distress arises as part of the transmission of monetary policy, and document the subsequent effect on output…. [W[e identify and compare the timing, duration, amplitude, and comovement of cycles in money, credit, and output. Regressions show that fi nancial distress events exacerbate business cycle downturns both in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and that a confluence of such events makes recessions even worse.

And this is from the concluding section:

[T]he narrative evidence strongly suggests, and the empirical work is at least consistent with, the claim that credit turmoil worsens recessions. The timing of cycles is likewise consistent with the work of Gilchrist, Yankov and Zakrajsek (2008) and others on the ability of corporate bond spreads to predictrecession in more recent periods.

The results are consistent with work, such as Barro and Ursua (2009), who find a high association between stock market crashes and large contractions, and Claessens Kose, and Terrones, who find an interaction between stock market crashes and tight money and credit….

The current episode combines elements of a credit crunch, asset price bust and banking crisis. It is consistent with the patterns we find using 140 years of US data. How does the current crisis measure up? Between August, 2007, and April, 2009, the difference between the yield on Baa bonds and long‐term Treasuries has moved up 342 basis points, a larger increase than seen in the 1929 contraction, and approaching the combined increase of 436 bp over both the Depression contractions. The percentage drop in S and P index of 42% is second only to the 78% of the Great Contraction…. Zarnowitz (1992) shows that business cycles downturns with panics are much more severe than others. Today because of deposit insurance, financial turmoil does not lead to panics and collapses in the money multiplier, and credit turmoil is less likely to feed into the money supply. The credit disturbance thus becomes relatively more important, given that disturbances on the asset side of the balance sheet no longer have as strong an influence on the money supply.

But there is nothing illusory about the relatively high level of economic activity from which a descent begins. It is real, and due in no small part to the availability of credit.

THE “HANGOVER” NARRATIVE AS A FALSE ANALOGY

A leading explanation of the Great Depression — and one that echoes today, in the aftermath of the Great Recession — is that Americans imbibed too much easy credit. Frederick Lewis Allen put it this way in his popular treatment of the Roaring Twenties and Great Crash, Only Yesterday (1931):

Prosperity was assisted … by two new stimulants to purchasing, each of which mortgaged the future but kept the factories roaring while it was being injected. The first was the increase in the installment buying. People were getting to consider it old-fashioned to limit their purchases to the amount of their cash balance; the thing to do was to “exercise their credit.” By the latter part of the decade, economists figured that 15 per cent of all retail sales were on an installment basis, and that there were some six billions of “easy payment” paper outstanding. The other stimulant was stock-market speculation. When stocks were skyrocketing in 1928 and 1929 it is probable that hundreds of thousands of people were buying goods with money which represented, essentially, a gamble on the business profits of the nineteen-thirties. It was fun while it lasted. (From Chapter 7, “Coolidge Prosperity.”

Thus:

Under the impact of the shock of panic, a multitude of ills which hitherto had passed unnoticed or had been offset by stock-market optimism began to beset the body economic, as poisons seep through the human system when a vital organ has ceased to function normally. Although the liquidation of nearly three billion dollars of brokers’ loans contracted credit, and the Reserve Banks lowered the rediscount rate, and the way in which the larger banks and corporations of the country had survived the emergency without a single failure of large proportions offered real encouragement, nevertheless the poisons were there; overproduction of capital; overambitious (expansion of business concerns; overproduction of commodities under the stimulus of installment buying and buying with stock-market profits… (From Chapter 13, “Crash!“)

And, finally:

Soon the mists of distance would soften the outlines of the nineteen- twenties, and men and women, looking over the pages of a book such as this, would smile at the memory of those charming, crazy days when the radio was a thrilling novelty, and girls wore bobbed hair and knee- length skirts, and a trans-Atlantic flyer became a god overnight, and common stocks were about to bring us all to a lavish Utopia. They would forget, perhaps, the frustrated hopes that followed the war, the aching disillusionment of the hard-boiled era, its oily scandals, its spiritual paralysis, the harshness of its gaiety; they would talk about the good old days …. (From Chapter 14, “Aftermath: 1930-1931.”)

The clear moral — in the view of Allen and many others, unto this day — is that America had overindulged in the Roaring Twenties and paid for it with a hangover, in the form of the Great Crash and subsequent Great Depression, which was in evidence by the time Only Yesterday was published.

The true story is that government caused the financial excesses of the Roaring Twenties, the evolution of the Great Crash into the Great Depression, and a deep recession that prolonged the Great Depression. This long, dismal story has been told many times; there is a fact-filled but concise retelling in the Mackinac Center’s “Great Myth of the Great Depression.” Jumping to the bottom line:

The genesis of the Great Depression lay in the irresponsible monetary and fiscal policies of the U.S. government in the late 1920s and early 1930s. These policies included a litany of political missteps: central bank mismanagement, trade-crushing tariffs, incentive-sapping taxes, mind-numbing controls on production and competition, senseless destruction of crops and cattle and coercive labor laws, to recount just a few. It was not the free market that

produced 12 years of agony; rather, it was political bungling on a grand scale.

The story ends with an assessment of the financial crisis that sparked the Great Recession:

The financial crisis that gripped America in 2008 ought to be a wake-up call. The fingerprints of government meddling are all over it. From 2001 to 2005, the Federal Reserve revved up the money supply, expanding it at a feverish double-digit rate. The dollar plunged in overseas markets and commodity prices soared. With the banks flush with liquidity from the Fed, interest rates plummeted and risky loans to borrowers of dubious merit ballooned. Politicians threw more fuel on the fire by jawboning banks to lend hundreds of billions of dollars for subprime mortgages. When the bubble burst, some of the very culprits who promoted the policies that caused it postured as our rescuers while endorsing new interventions, bigger government, more inflation of money and credit and massive taxpayer bailouts of failing firms. Many of them are also calling for higher taxes and tariffs, the very nonsense that took a recession in 1930 and made it a long and deep depression.

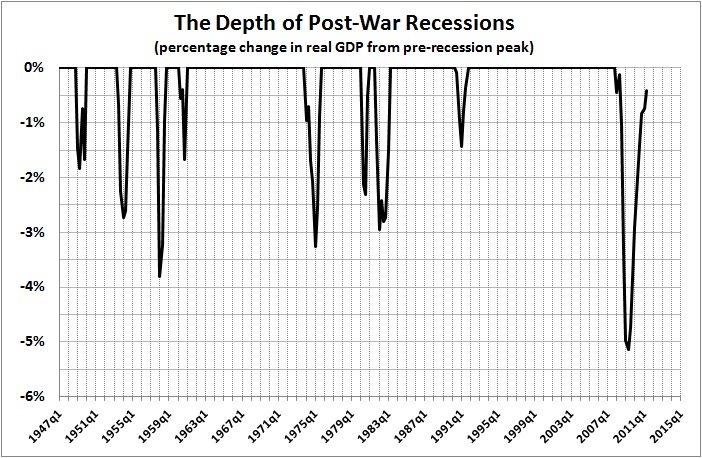

Just how bad is the government-caused Great Recession? It is the worst recession since the end of World War II and, therefore, the worst downturn since the Great Depression:

Derived from quarterly estimates of real GDP provided by the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

To paraphrase Ronald Reagan: Money and credit are not the problem. Government policies — including the mismanagement of money and credit — are the problem.

FREE FINANCIAL MARKETS ARE THE SOLUTION

Government control and monopolization of money, banking, and credit has been the norm for so long that it is taken for granted by almost everyone. But the record of government misfeasance and malfeasance with respect to economic activity (barely touched on above) is such that the proponents of governmental interventions should bear the burden of proving that those interventions are warranted.

I will close with another paraphrase, this time of Winston Churchill: the free market is the least effective means of making resource-allocation decisions that foster material progress, except for all the rest.

Read on:

Mr. Greenspan Doth Protest Too Much

Economic Growth since WWII

The Price of Government

The Fed and Business Cycles

The Commandeered Economy

The Price of Government Redux

The Mega-Depression

Does the CPI Understate Inflation?

Ricardian Equivalence Reconsidered

The Real Burden of Government

Toward a Risk-Free Economy

The Rahn Curve at Work

How the Great Depression Ended

The Illusion of Prosperity and Stability

The “Forthcoming Financial Collapse”

Experts and the Economy

Estimating the Rahn Curve: Or, How Government Inhibits Economic Growth

The Deficit Commission’s Deficit of Understanding

The Bowles-Simpson Report

The Bowles-Simpson Band-Aid

The Great Recession is Over

The Stagnation Thesis

Government Failure: An Example

The Evil That Is Done with Good Intentions

America’s Financial Crisis Is Now

The Great Recession Is Not Over