UPDATED (08/18/12) BELOW

This is the third installment of a series that explores the true nature of liberty, how liberty depends on society, how society (properly understood) has been eclipsed by statism and its artifacts, and how society — and therefore liberty — might re-emerge in the United States. In this installment, I take up the second of several possible objections to my model of a society’s essence and workings. This series will close with a blueprint for the restoration of society and liberty in America.

If you have not read the first two installments, “Liberty and Society” and “The Eclipse of ‘Old America’,” I recommend that you do so before you continue. This post addresses the following question: Is Genetic Kinship an Indispensable Aspect of Society?

In “Liberty and Society,” I define society as “an enduring and cooperating social group whose members have developed organized patterns of relationships through interaction with one another.” Near the end of the post, I say this:

A society coheres around genetic kinship, and is defined by its common culture, which includes its moral code. The culture is developed, transmitted through, and enforced by the voluntary institutions of society (civil society). The culture is the product of trial and error, where those elements that become part of received culture serve societal coherence and — in the best case — help it to thrive. Coherence and success depend also on the maintenance of mutual respect, trust, and forbearance among society’s members. Those traits arise in part from the sharing of a common culture (which is an artifact of societal interaction) and from genetic kinship, which is indispensable to societal coherence. If the foregoing description is correct, there is one aspect of society — and one only — that a society cannot “manufacture” through its social processes. That aspect is genetic-cultural kinship.

In the sequel, “The Eclipse of ‘Old America’,” there is this:

The United States, for a very long time, was a polity whose disparate parts cohered, regionally if not nationally, because the experience of living in the kind of small community sketched above was a common one. Long after the majority of Americans came to live in urban complexes, a large fraction of the residents of those complexes had grown up in small communities.

This was Old America — and it was predominant for almost 200 years after America won its independence from Britain. Old America‘s core constituents, undeniably, were white, and they had much else in common: observance of the Judeo-Christian tradition; British and north-central European roots; hard work and self-reliance as badges of honor; family, church, and club as cultural transmitters, social anchors, and focal points for voluntary mutual aid.

The focus of this post is the indispensable contribution of genetic kinship to society. Before I continue, I want to make it clear that I do not use “society” in the loose way that politicians do, that is, as a feel-good word for “nation.” The United States, as a nation, may comprise societies of the kind defined above, but the United States is not a society. It is a political convenience, held together by force, not by mutual trust, respect, and forbearance — which are the operational characteristics of a society.

Mutual trust, respect, and forbearance arise from the emotional force of genetic kinship. They may be mimicked in arrangements of convenience, such as economic ones. But those arrangements last only as long as they are profitable to all parties.

Arrangements of convenience may be facilitated by social bonding, but they cannot replace social bonding. For example, disparate peoples may trade with each other, to their mutual advantage, but they are not bound to each other emotionally. History is replete with examples of peoples who have turned against each other, despite their economic ties. Diplomatic ties are even less binding, because of their superficiality.

Whence the emotional bonds of genetic kinship? Are they found only in the nuclear family? (No.) Do they encompass the extended family? (Yes.) Are they enhanced by social relationships (e.g., church and club)? (Yes.) Do they extend to broad racial-ethnic groupings? (Yes.)

Emotional bonds may be reinforced (or not) by familial and social relationships, but they begin with racial-ethnic (genetic) kinship:

[S]tudies have demonstrated that relatedness is often important for human altruism in that humans are inclined to behave more altruistically toward kin than toward unrelated individuals.[22] Many people choose to live near relatives, exchange sizable gifts with relatives, and favor relatives in wills in proportion to their relatedness.[22]

A study interviewed several hundred women in Los Angeles to study patterns of helping between kin versus non-kin. While non-kin friends were willing to help one another, their assistance was far more likely to be reciprocal. The largest amounts of non-reciprocal help, however, were reportedly provided by kin. Additionally, more closely related kin were considered more likely sources of assistance than distant kin.[23] Similarly, several surveys of American college students found that individuals were more likely to incur the cost of assisting kin when a high probability that relatedness and benefit would be greater than cost existed. Participants’ feelings of helpfulness were stronger toward family members than non-kin. Additionally, participants were found to be most willing to help those individuals most closely related to them. Interpersonal relationships between kin in general were more supportive and less Machiavellian than those between non-kin.[24]….

A study of food-sharing practices on the West Caroline islets of Ifaluk determined that food-sharing was more common among people from the same islet, possibly because the degree of relatedness between inhabitants of the same islet would be higher than relatedness between inhabitants of different islets. When food was shared between islets, the distance the sharer was required to travel correlated with the relatedness of the recipient—a greater distance meant that the recipient needed to be a closer relative. The relatedness of the individual and the potential inclusive fitness benefit needed to outweigh the energy cost of transporting the food over distance.[26]

Humans may use the inheritance of material goods and wealth to maximize their inclusive fitness. By providing close kin with inherited wealth, an individual may improve his or her kin’s reproductive opportunities and thus increase his or her own inclusive fitness even after death. A study of a thousand wills found that the beneficiaries who received the most inheritance were generally those most closely related to the will’s writer. Distant kin received proportionally less inheritance, with the least amount of inheritance going to non-kin.[27]

A study of childcare practices among Canadian women found that respondents with children provide childcare reciprocally with non-kin. The cost of caring for non-kin was balanced by the benefit a woman received—having her own offspring cared for in return. However, respondents without children were significantly more likely to offer childcare to kin. For individuals without their own offspring, the inclusive fitness benefits of providing care to closely related children might outweigh the time and energy costs of childcare.[28]

Family investment in offspring among black South African households also appears consistent with an inclusive fitness model.[29] A higher degree of relatedness between children and their caregivers frequently correlated with a higher degree of investment in the children, with more food, health care, and clothing being provided. Relatedness between the child and the rest of the household also positively associated with the regularity of a child’s visits to local medical practitioners and with the highest grade the child had completed in school. Additionally, relatedness negatively associated with a child’s being behind in school for his or her age.

Observation of the Dolgan hunter-gatherers of northern Russia suggested that, while reciprocal food-sharing occurs between both kin and non-kin, there are larger and more frequent asymmetrical transfers of food to kin. Kin are also more likely to be welcomed to non-reciprocal meals, while non-kin are discouraged from attending. Finally, even when reciprocal food-sharing occurs between families, these families are often very closely related, and the primary beneficiaries are the offspring.[30]

Other research indicates that violence in families is more likely to occur when step-parents are present and that “genetic relationship is associated with a softening of conflict, and people’s evident valuations of themselves and of others are systematically related to the parties’ reproductive values”.[31]

Numerous other studies pertaining to kin selection exist, suggesting how inclusive fitness may work amongst peoples from the Ye’kwana of southern Venezuela to the Gypsies of Hungary to even the doomed Donner Party of the United States.[32][33][34] Various secondary sources provide compilations of kin selection studies.[35][36] [from Wikipedia, “Kin selection,” as of 08/14/12]

* * *

[E.O.] Wilson used sociobiology and evolutionary principles to explain the behavior of the social insects and then to understand the social behavior of other animals, including humans, thus established sociobiology as a new scientific field. He argued that all animal behavior, including that of humans, is the product of heredity, environmental stimuli, and past experiences, and that free will is an illusion. He has referred to the biological basis of behaviour as the “genetic leash.”[17] The sociobiological view is that all animal social behavior is governed by epigenetic rules worked out by the laws of evolution. This theory and research proved to be seminal, controversial, and influential.[18]

The controversy of sociobiological research is in how it applies to humans. The theory established a scientific argument for rejecting the common doctrine of tabula rasa, which holds that human beings are born without any innate mental content and that culture functions to increase human knowledge and aid in survival and success. In the final chapter of the book Sociobiology and in the full text of his Pulitzer Prize-winning On Human Nature, Wilson argues that the human mind is shaped as much by genetic inheritance as it is by culture (if not more). There are limits on just how much influence social and environmental factors can have in altering human behavior….

Wilson has argued that the “unit of selection is a gene, the basic element of heredity. The target of selection is normally the individual who carries an ensemble of genes of certain kinds.” With regard to the use of kin selection in explaining the behavior of eusocial insects, Wilson said to Discover magazine, the “new view that I’m proposing is that it was group selection all along, an idea first roughly formulated by Darwin.”[22] [from Wikipedia, “E.O. Wilson,” as of 08/14/12]

* * *

Wilson suggests the equation for Hamilton’s rule:[19]

-

- rb > c

(where b represents the benefit to the recipient of altruism, c the cost to the altruist, and r their degree of relatedness) should be replaced by the more general equation

-

- (rbk + be) > c

in which bk is the benefit to kin (b in the original equation) and be is the benefit accruing to the group as a whole. He then argues that, in the present state of the evidence in relation to social insects, it appears that be>rbk, so that altruism needs to be explained in terms of selection at the colony level rather than at the kin level. However, it is well understood in social evolution theory that kin selection and group selection are not distinct processes, and that the effects of multi-level selection are already fully accounted for in Hamilton’s original rule, rb>c.[20] [from Wikipedia, “Group selection,” as 0f 08/14/12]

The idea that social bonding has a deep, genetic basis is beyond the ken of leftists and pseudo-libertarian rationalists. Both prefer to deny reality, though for different reasons. Leftists like to depict the state as society. Pseudo-libertarian rationalists seem to believe that social bonding is irrelevant to cooperative, mutually beneficial behavior; life, to them, is an economic arrangement.

Leftists and libertarians like to slander the mutual attraction of genetic kin by calling it “tribalism.” On that subject, the author of Foseti writes:

People are – in general – tribal. Let’s take it for granted that we all wish that this were not so. Further, let’s take it for granted that some individual people are much more tribal than others.

The fact remains, however, that people are tribal. It’s one thing to suggest that people should not be tribal in their daily dealings with others. Let’s stipulate that this is moral. It does not, however, follow that it would be moral to organize society around the principle the people will in fact act anti-tribally….

Lots of progressives (especially those of the libertarian sort) are fond of saying that restricting immigration is tribal. They simply can’t support immigration restrictions because they oppose tribalism.

There is no better way of demonstrating your high-status in today’s society than proclaiming your anti-tribalism. You should therefore be skeptical of these proclamations. However, many people are indeed not particularly tribal.

Your humble blogger is not a tribal person. There is no sort of person that I see on the street and say to myself, “wow, I bet he and I have a lot in common – we should look out for each other.” Temperamentally, I’m very much an individualist type. But it’s wishful thinking to generalize from my personal preferences to population-wide-shoulds.

Tribalism is, has always been, and likely always will be a feature of human societies.

Occasionally, we get not-so-gentle reminders that people are tribal. We would do well to learn. Here’s a more light-hearted example. Here’s a reminder that democratic politics is always tribal.

You’re free, of course, to consider yourself above tribalism. However, if you do so, you’ll be an idiot when you try to describe geopolitics, local politics, national politics, and public policies in general. By all means, bury your head in the sand, just don’t preach while you’re down there.

James_G makes a nice analogy in this post. He likens anti-tribal beliefs to communist beliefs. It’s true that some groups of humans can function reasonably well under communistic conditions. It’s similarly true that many human beings are not particularly tribal. However, it’s dangerously immoral to generalize from these exceptions to the general conclusions that communism works on a large scale or that all countries should be rainbow nations…. [from “The immorality of anti-tribalism,” July 25, 2012]

In America, the pursuit of happiness in the form of money has sundered many a tribal community. (See “The Eclipse of ‘Old America’,” especially the 11th and 12th paragraphs.) But tribalism nevertheless remains a potent force in America:

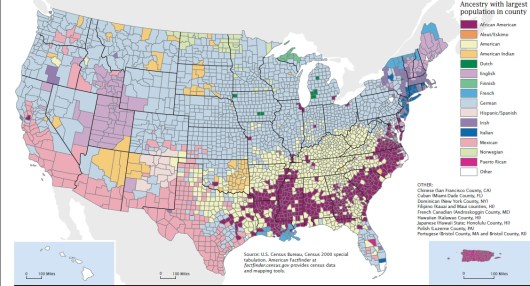

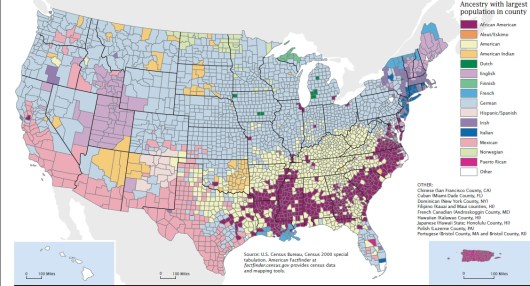

Source: Census.gov, Ancestry: 2000 — Census 2000 Brief, Figure 3. (Right-click to open in a new tab, then click to enlarge.)

I venture to say that the “Americans” who predominate in large swaths of the South are the descendants of the English and Scots-Irish settlers of the colonial and early post-colonial era. They are “Americans” because their ancestors were (for the most part) the Americans of yore.

Not represented in the graph, because it is based on county-level statistics, are the high concentrations of Jews in many urban areas (especially in and around New York City and Miami), the coalescence of Arabs in the Detroit area, and the numerous ethnic enclaves (e.g., Chinese, Czech, Greek, Korean, Polish, Swedish, and Thai) — urban, semi-rural, and rural — that persist long after the original waves of immigration that led to their formation.

If genetic kinship is such a binding force, why is the closest kind of genetic kinship — the nuclear family — so often dysfunctional? Nuclear families are notoriously prone to strife, or so it would seem if one were to count novels and screenplays in evidence. Novels and screenplays are not dispositive, of course, because they emphasize strife for dramatic purposes. That said, there is a lot of evidence to suggest that the American nuclear family is a less binding force than it used to be. But that is to be expected, given the interventions by the state that have eased divorce and lured women out of the home (e.g., affirmative action, subsidies for day care, mandated coverages for employer-provided health insurance).

There are other reasons to reject the (exaggerated) dysfunctionality of the nuclear family as evidence against the importance of genetic kinship to social bonding:

1. Strife is inevitable where humans interact, and family life affords a disproportionate number of opportunities for interaction. (For example, conflicts between the members of a nuclear family — parent vs. child, sibling vs. sibling — often begin during the childhood or adolescence of one or all parties to the conflict.)

2. Blood ties have a way of overcoming “bad blood” when a family member is in need of help. (Thus, for example, children of middle-age and older often are supportive of needful siblings and aged parents out of duty, not love.)

3. Many a person compensates for tense or distant relations with parents and siblings by maintaining close ties to grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins.

This is not to say that the bonds of genetic kinship in America are everywhere as strong as in years past. The state’s interventions, the search for greener pastures, and the inexorable force of cross-racial and cross-ethnic sexual attraction have led to a more homogenized America.

But genetic kinship will always be a strong binding force, even where the kinship is primarily racial. Racial kinship boundaries, by the way, are not always and necessarily the broad ones suggested by the classic trichotomy of Caucasoid, Mongoloid, Negroid. (If you want to read for yourself about the long, convoluted, diffuse, and still controversial evolutionary chains that eventuated in the sub-species homo sapiens sapiens, to which all humans are assigned arbitrarily, without regard for their distinctive differences, begin here, here, here, and here.)

The obverse of of genetic kinship is “diversity,” which often is touted as a good thing by anti-tribalist social engineers. But “diversity” is not a good thing when it comes to social bonding. Michael Jonas reports on a study by Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam, “E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-first Century“:

It has become increasingly popular to speak of racial and ethnic diversity as a civic strength. From multicultural festivals to pronouncements from political leaders, the message is the same: our differences make us stronger.

But a massive new study, based on detailed interviews of nearly 30,000 people across America, has concluded just the opposite. Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam — famous for “Bowling Alone,” his 2000 book on declining civic engagement — has found that the greater the diversity in a community, the fewer people vote and the less they volunteer, the less they give to charity and work on community projects. In the most diverse communities, neighbors trust one another about half as much as they do in the most homogenous settings. The study, the largest ever on civic engagement in America, found that virtually all measures of civic health are lower in more diverse settings….

…Putnam’s work adds to a growing body of research indicating that more diverse populations seem to extend themselves less on behalf of collective needs and goals.

His findings on the downsides of diversity have also posed a challenge for Putnam, a liberal academic whose own values put him squarely in the pro-diversity camp. Suddenly finding himself the bearer of bad news, Putnam has struggled with how to present his work. He gathered the initial raw data in 2000 and issued a press release the following year outlining the results. He then spent several years testing other possible explanations.

When he finally published a detailed scholarly analysis in June in the journal Scandinavian Political Studies, he faced criticism for straying from data into advocacy. His paper argues strongly that the negative effects of diversity can be remedied, and says history suggests that ethnic diversity may eventually fade as a sharp line of social demarcation.

“Having aligned himself with the central planners intent on sustaining such social engineering, Putnam concludes the facts with a stern pep talk,” wrote conservative commentator Ilana Mercer, in a recent Orange County Register op-ed titled “Greater diversity equals more misery.”….

The results of his new study come from a survey Putnam directed among residents in 41 US communities, including Boston. Residents were sorted into the four principal categories used by the US Census: black, white, Hispanic, and Asian. They were asked how much they trusted their neighbors and those of each racial category, and questioned about a long list of civic attitudes and practices, including their views on local government, their involvement in community projects, and their friendships. What emerged in more diverse communities was a bleak picture of civic desolation, affecting everything from political engagement to the state of social ties….

After releasing the initial results in 2001, Putnam says he spent time “kicking the tires really hard” to be sure the study had it right. Putnam realized, for instance, that more diverse communities tended to be larger, have greater income ranges, higher crime rates, and more mobility among their residents — all factors that could depress social capital independent of any impact ethnic diversity might have.

“People would say, ‘I bet you forgot about X,'” Putnam says of the string of suggestions from colleagues. “There were 20 or 30 X’s.”

But even after statistically taking them all into account, the connection remained strong: Higher diversity meant lower social capital. In his findings, Putnam writes that those in more diverse communities tend to “distrust their neighbors, regardless of the color of their skin, to withdraw even from close friends, to expect the worst from their community and its leaders, to volunteer less, give less to charity and work on community projects less often, to register to vote less, to agitate for social reform more but have less faith that they can actually make a difference, and to huddle unhappily in front of the television.”

“People living in ethnically diverse settings appear to ‘hunker down’ — that is, to pull in like a turtle,” Putnam writes….

In a recent study, [Harvard economist Edward] Glaeser and colleague Alberto Alesina demonstrated that roughly half the difference in social welfare spending between the US and Europe — Europe spends far more — can be attributed to the greater ethnic diversity of the US population. Glaeser says lower national social welfare spending in the US is a “macro” version of the decreased civic engagement Putnam found in more diverse communities within the country.

Economists Matthew Kahn of UCLA and Dora Costa of MIT reviewed 15 recent studies in a 2003 paper, all of which linked diversity with lower levels of social capital. Greater ethnic diversity was linked, for example, to lower school funding, census response rates, and trust in others. Kahn and Costa’s own research documented higher desertion rates in the Civil War among Union Army soldiers serving in companies whose soldiers varied more by age, occupation, and birthplace.

Birds of different feathers may sometimes flock together, but they are also less likely to look out for one another. “Everyone is a little self-conscious that this is not politically correct stuff,” says Kahn….

In his paper, Putnam cites the work done by Page and others, and uses it to help frame his conclusion that increasing diversity in America is not only inevitable, but ultimately valuable and enriching. As for smoothing over the divisions that hinder civic engagement, Putnam argues that Americans can help that process along through targeted efforts. He suggests expanding support for English-language instruction and investing in community centers and other places that allow for “meaningful interaction across ethnic lines.”

Some critics have found his prescriptions underwhelming. And in offering ideas for mitigating his findings, Putnam has drawn scorn for stepping out of the role of dispassionate researcher. “You’re just supposed to tell your peers what you found,” says John Leo, senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, a conservative think tank…. [from “The downside of diversity,” The Boston Globe (boston.com), August 5, 2007]

Putnam’s reluctance about releasing the study and his attempt to soften its implications say much about the relationship that anti-tribalist social engineers (like Putnam) have with truth. Here is more from John Leo:

Putnam’s study reveals that immigration and diversity not only reduce social capital between ethnic groups, but also within the groups themselves. Trust, even for members of one’s own race, is lower, altruism and community cooperation rarer, friendships fewer. The problem isn’t ethnic conflict or troubled racial relations, but withdrawal and isolation. Putnam writes: “In colloquial language, people living in ethnically diverse settings appear to ‘hunker down’—that is, to pull in like a turtle.”…

Neither age nor disparities of wealth explain this result. “Americans raised in the 1970s,” he writes, “seem fully as unnerved by diversity as those raised in the 1920s.” And the “hunkering down” occurred no matter whether the communities were relatively egalitarian or showed great differences in personal income. Even when communities are equally poor or rich, equally safe or crime-ridden, diversity correlates with less trust of neighbors, lower confidence in local politicians and news media, less charitable giving and volunteering, fewer close friends, and less happiness….

Putnam has long been aware that his findings could have a big effect on the immigration debate. Last October, he told the Financial Times that “he had delayed publishing his research until he could develop proposals to compensate for the negative effects of diversity.” He said it “would have been irresponsible to publish without that,” a quote that should raise eyebrows. Academics aren’t supposed to withhold negative data until they can suggest antidotes to their findings…

Though Putnam is wary of what right-wing politicians might do with his findings, the data might give pause to those on the left, and in the center as well. If he’s right, heavy immigration will inflict social deterioration for decades to come, harming immigrants as well as the native-born. Putnam is hopeful that eventually America will forge a new solidarity based on a “new, broader sense of we.” The problem is how to do that in an era of multiculturalism and disdain for assimilation…. [from “Bowling with Our Own,” City Journal, June 25, 2007]

* * *

UPDATE (08/18/12):

I can do no better at this point than inject some passages from Byron M. Roth’s The Perils of Diversity: Immigration and Human Nature. The following observations, taken from Chapter I, are supported by the rich detail that Roth delivers in the following several hundred pages of the book:

…Multiculturalists … ignore the historical record that suggests that social harmony among different ethnic and language groups is at best rare, and where it exists, tenuous. The history of Europe, whatever else it is, is one long tale of religious and ethnic conflict, almost ceaseless war, and the slaughter and the destruction it entails. The enlightenment, and the scientific advances it engendered, did nothing to mitigate this tale of horrific and bloody conflict, with the twentieth century exhibiting the most lethal and unsparing carnage in European history. In addition, in the twentieth century, class conflict was raised to a level in Europe and Asia never seen before. Communist rulers in Europe and Asia effectively divided their societies along economic lines and managed over the century to slaughter even more people than the ethnically based World Wars I and II.

The breakup of the British Empire led to bloody civil strife throughout the former colonies among the disparate peoples held together by British force of arms. The civil war that led to the partition of India and Pakistan left an estimated one million dead in its wake. Similar terrible and murderous turmoil in Southeast Asia, in for example Cambodia and Vietnam, followed the withdrawal of the European Colonial powers. Among the former European colonies in Africa, even today, civil strife is rampant.

In the wake of the fall of Communism those multiethnic societies that had been held together by authoritarian dictators quickly fell asunder. Czechoslovakia divided in a peaceful and largely amiable way. Yugoslavia, on the other hand, was torn by vicious civil war and genocidal ethnic cleansing. Iraq, after the fall of Saddam Hussein, presents a similar case. The ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a different and bloody example of the difficulties of establishing harmony among groups of differing cultures and religions. Even Belgium, (the seat of the European Union Parliament) is in danger of splitting into its Dutch-speaking and French-speaking halves.8 Canadians of French and English ancestry are grappling with similar problems. In addition, there is a fundamental inconsistency at the base of the multiculturalist program, in that it applauds ethnic minorities who maintain their cultural traditions, but looks askance at majority populations who wish to do the same. Political elites in all Western societies take a negative view of those who wish to preserve their traditional values and patterns of living and question whether those patterns can be sustained in the face of large numbers of newcomers who do not share those values or are actually hostile to them….

…[T]he social science evidence that a harmonious society composed of identifiable ethnic groups with different cultural and religious backgrounds can be arranged is, almost without exception, negative. Has some new type of social engineering appeared which would allow this historic pattern to be broken? Has some new sort of human being been born who will not repeat the follies of his ancestors? Will the world find a way to emulate the example of the Swiss? Policy makers should be trying to understand how the Swiss have managed to preserve their experiment in multicultural harmony for so long, when so many others have failed so utterly. Perhaps Switzerland can be a model for the new multicultural societies? On the other hand, maybe Switzerland is a special case that cannot be copied. Switzerland, for all its ethnic harmony, is, in effect, a confederation of separate but closely related European ethnicities who reside in different cantons, who speak their own languages (French, German, Italian, and Native Swiss), and maintain their ethnic customs and tastes. It would be reasonable to ask if such an arrangement could be widely duplicated in very different settings, but few in the multicultural camp appear interested in such a question.

Similarly, the assimilationists who support mass immigration seem equally nonchalant about the evidence for their position. Clearly, the history of immigration to the United States has been fortunate and largely successful. But in the past virtually all successful immigration was from European cultures very similar to that of the original English settlers. In addition, those settlers usually came with similar skills and abilities, often better than those of the earlier settlers, and generally had little difficulty in competing with them. Once in America, they could easily blend in, there being few physical or social features which set them apart. Usually they came in small numbers over an extended period of time and were forced to acquire the language of their host country if they expected to thrive. This was because (except for German and French speakers in some areas) no one group could sustain communities sufficiently large as to be economically independent and thereby sustain their native language for general commerce. As a counterexample, the French community in Quebec did possess sufficient size and was therefore able to maintain its language as well as its ethnic identity.

The United States was so vast and the opportunities it offered so generous that group conflict was generally muted. Conflict among immigrant Europeans was generally limited to the crowded multiethnic coastal cities, and those who wished to avoid those conflicts could migrate to the interior, often gravitating to ethnic enclaves. Even in those less crowded settings, however, conflict was not uncommon, though it usually took the form of political differences over the place of religion in society and the nature of education. Is this an immigration pattern that could be replicated today in modern societies when the immigrant groups come in large numbers from vastly different cultural and ethnic backgrounds compared to the residents of their host countries? Can this model work in crowded Western Europe where land for housing is limited and where unemployment remains at chronically high levels? In other words, is the American immigration experience prior to 1965 an exceptional one? Can it be the model for future immigration cycles or are the conditions today so different as to make the model inapplicable? These are questions that need to asked, but rarely are.

A clear implication of Roth’s analysis is that conflict — political, if not violent — is bound to result from racial-ethnic-cultural commingling — unless the disparate groups are geographically separated and politically autonomous in all respects (except, perhaps, that they each bear a “fair share” of the cost of a common defense).

* * *

The idea that society– properly defined and understood — requires genetic kinship is nevertheless anathema to anti-tribalist social tinkerers of Putnam’s ilk. It is ironic (but not surprising) that anti-tribalists often seek connections with “kindred” souls. The leftist groves of academe are notorious for their exclusion of libertarians and conservatives, but an academic mistakes his like-minded colleagues for altruistic kinsmen at his own peril. (I speak from the experience of years in a quasi-academic think-tank, and as a former “friend” in many a work-based “friendship.”)

Libertarians, who are notoriously individualistic and aloof, also seek to bond with like-minded persons. Libertarians are responsible for the less-than-successful Free State Project and for seasteading (formally neutral in its ideology, but mainly attractive to libertarians). I expect such experiments in coexistence, if they get off the ground, to be as inconsequential as their anti-libertarian equivalent: the commune. Communes have been around for a while, of course, though none of them has lasted long or attracted many adherents. They are, after all, nothing more than economic arrangements with some “Kumbaya” thrown in.

So, yes, genetic kinship is indispensable to society, where society is properly understood as “an enduring and cooperating social group whose members have developed organized patterns of relationships through interaction with one another.” But, as I discuss here, not all societies based on genetic kinship are created equal. Trying to make them equal is a fool’s errand.

The fourth installment is here.

Related posts:

On Liberty

Rights, Liberty, the Golden Rule, and the Legitimate State

What Is Conservatism?

Zones of Liberty

Society and the State

I Want My Country Back

The Golden Rule and the State

Government vs. Community

Evolution, Human Nature, and “Natural Rights”

More about Conservative Governance

The Meaning of Liberty

Evolution and the Golden Rule

Understanding Hayek

The Golden Rule as Beneficial Learning

True Libertarianism, One More Time

Human Nature, Liberty, and Rationalism

Why Conservatism Works

Reclaiming Liberty throughout the Land

Rush to Judgment

Secession, Anyone?

Race and Reason: The Achievement Gap — Causes and Implications

Liberty and Society

The Eclipse of “Old America”

The diamond-shaped space is attractive because it has been created, over the decades, by promising more freedom but, in fact, delivering less. Despite that failure, the promises are repeated ad nauseam and drummed into the minds gullible citizens, even as their freedom is being stripped away.

The diamond-shaped space is attractive because it has been created, over the decades, by promising more freedom but, in fact, delivering less. Despite that failure, the promises are repeated ad nauseam and drummed into the minds gullible citizens, even as their freedom is being stripped away.