UPDATED on 04/17/10, to include GDP estimates for 2009 and slight revisions to GDP estimates for earlier years. The bottom line remains the same: The price of government is exorbitant.

he federal government is mounting an economic intervention on a scale unseen since World War II. The excuse for this intervention is that without it the present recession will turn into a full-blown depression. Yet, with the Democrats’ and RINOs’ “stimulus” barely underway, the economy already shows signs of rebounding from an economic dip that bears no comparison with the calamitous gulch that was the Great Depression.

Despite the horror stories about a financial meltdown, what we have experienced since late 2007 is not much more than the downside of a typical, post-World War II business cycle. (For more on that score, see this post — especially the third graph and related discussion.) Would it have been worse were all failing financial institutions allowed to fail? I doubt it. Hard, fast failure leaves in its wake opportunities for the organization of new ventures by investors who still have money (and there are plenty of them). But those same investors are being shouldered out and scared off by Obama’s schemes for nationalization, taxation, regulation, and redistribution.

What we are seeing is the continuation of a death-spiral that began in the early 1900s. Do-gooders, worry-warts, control freaks, and economic ignoramuses see something “bad” and — in their misguided efforts to control natural economic forces (which include business cycles) — make things worse. The most striking event in the death-spiral is the much-cited Great Depression, which was caused by government action, specifically the loose-tight policies of the Federal Reserve, Herbert Hoover’s efforts to engineer the economy, and — of course — FDR’s benighted New Deal. (For details, see this, and this.)

But, of course, the worse things get, the greater the urge to rely on government. Now, we have “stimulus,” which is nothing more than an excuse to greatly expand government’s intervention in the economy. Where will it lead us? To a larger, more intrusive government that absorbs an ever larger share of resources that could be put to productive use, and counteracts the causes of economic growth.

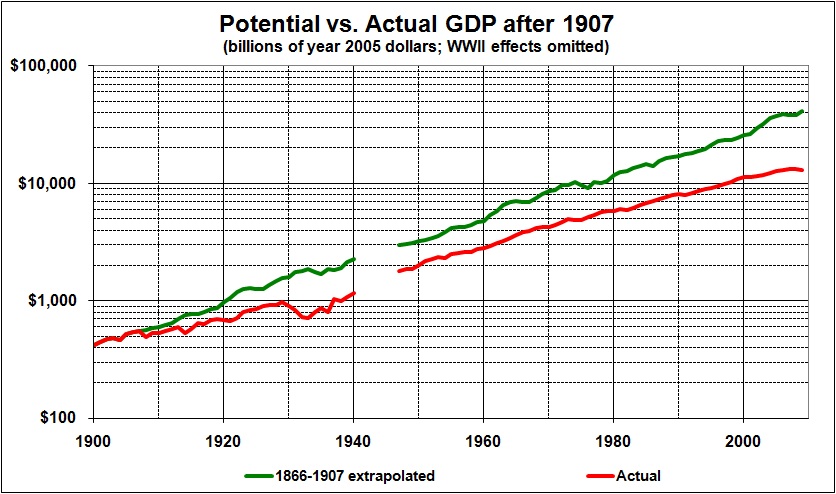

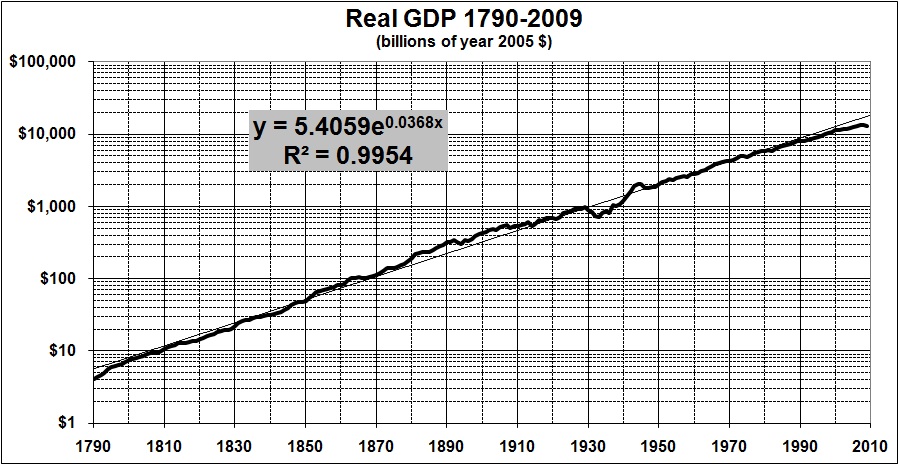

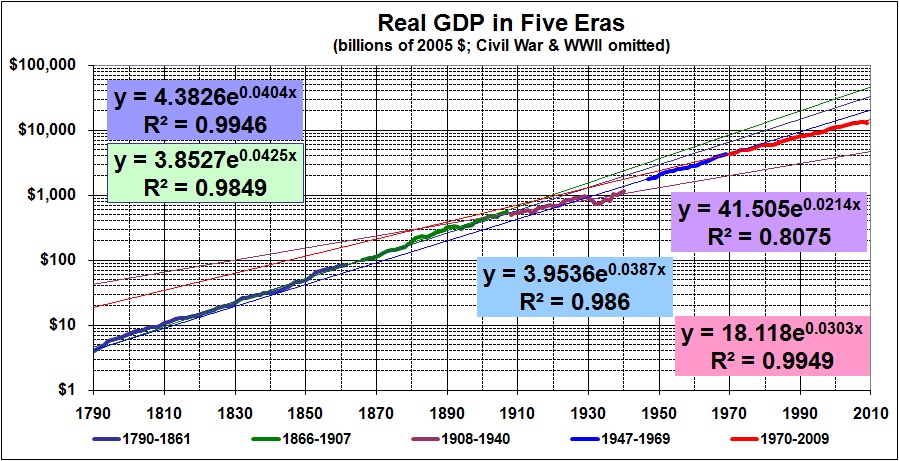

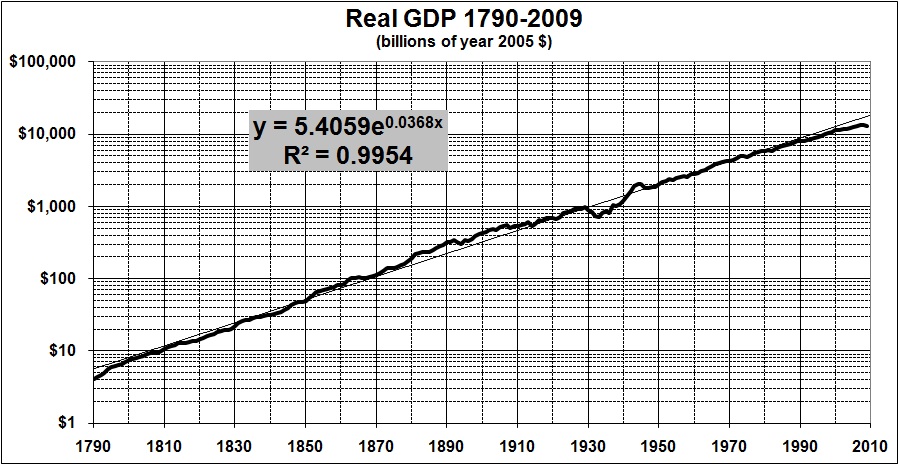

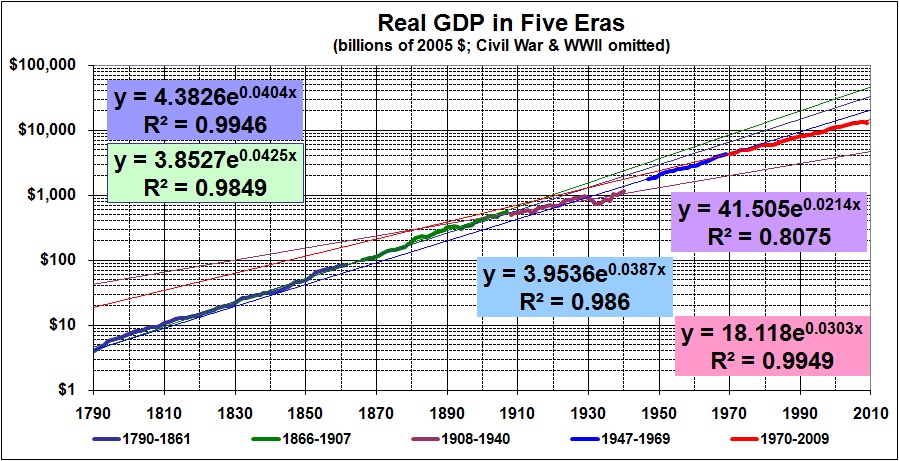

Can we measure the price of government intervention? I believe that we can do so, and quite easily. The tale can be told in three graphs, all derived from constant-dollar GDP estimates available here. The numbers plotted in each graph exclude GDP estimates for the years in which the U.S. was involved in or demobilizing from major wars, namely, 1861-65, 1918-19, and 1941-46. GDP values for those years — especially for the peak years of World War II — present a distorted picture of economic output. Without further ado, here are the three graphs:

The trend line in the first graph indicates annual growth of about 3.7 percent over the long run, with obviously large deviations around the trend. The second graph contrasts economic growth through 1907 with economic growth since: 4.2 percent vs. 3.6 percent. But lest you believe that the economy of the U.S. somehow began to “age” in the early 1900s, consider the story implicit in the third graph:

- 1790-1861 — annual growth of 4.1 percent — a booming young economy, probably at its freest

- 1866-1907 — annual growth of 4.3 percent — a robust economy, fueled by (mostly) laissez-faire policies and the concomitant rise of technological innovation and entrepreneurship

- 1970-2008 — annual growth of 3.1 percent — an economy sagging under the cumulative weight of “progressivism,” New Deal legislation, LBJ’s “Great Society” (with its legacy of the ever-expanding and oppressive welfare/transfer-payment schemes: Medicare, Medicaid, a more generous package of Social Security benefits), and an ever-growing mountain of regulatory restrictions.

Had the economy of the U.S. not been deflected from its post-Civil War course, GDP would now be about three times its present level. (Compare the trend lines for 1866-1907 and 1970-2008.) If that seems unbelievable to you, it shouldn’t: $100 compounded for 100 years at 4.3 percent amounts to $6,700; $100 compounded for 100 years at 3.1 percent amounts to $2,100. Nothing other than government intervention (or a catastrophe greater than any we have known) could have kept the economy from growing at more than 4 percent.

What’s next? Unless Obama’s megalomaniacal plans are aborted by a reversal of the Republican Party’s fortunes, the U.S. will enter a new phase of economic growth — something close to stagnation. We will look back on the period from 1970 to 2008 with longing, as we plod along at a growth rate similar to that of 1908-1940, that is, about 2.2 percent. Thus:

- If GDP grows at 2.2 percent through 2109, it will be 58 percent lower than if we plod on at 3.1 percent.

- If GDP grows at 2.2 percent for through 2109, it will be only 4 percent of what it would have been had it continued to grow at 4.3 percent after 1907.

The latter disparity may seem incredible, but scan the lists here and you will find even greater cross-national disparities in per capita GDP. Go here and you will find that real, per capita GDP in 1790 was only 4.6 percent of the value it had attained 218 years later. Our present level of output seems incredible to citizens of impoverished nations, and it would seem no less incredible to an American of 1790. In sum, vast disparities can and do exist, across nations and time. We have every reason to believe in the possibility of a sustained growth rate of 4.4 percent, as against one of 2.2 percent, because we have experienced both.

We should look on the periods 1908-1940 and 1970-2009 as aberrations, and take this lesson from those periods: Big government inflicts great harm on almost everyone (politicians and bureaucrats being the main exceptions), including its intended beneficiaries. Such is the price of government when it does more than “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, [and] provide for the common defence” in order to “promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.”