UPDATED 12/13/14 — This update consists of a comment about my estimate of the Rahn curve. I have just published a much better estimate of the curve for the post-World War II era.

UPDATED 12/28/11 — This update incorporates GDP and government spending statistics for 2010 and corrects a minor discrepancy in the estimation of government spending. Also, there are new, easier-to-read graphs. The bottom line is the same as before: Government spending and everything that goes with it (including regulation) is destructive of economic growth.

UPDATED 09/19/13 — This version incorporates two later posts “Estimating the Rahn Curve: A Sequel” (01/24/12) and “More Evidence for the Rahn Curve” (05/27/12).

* * *

The theory behind the Rahn Curve is simple — but not simplistic. A relatively small government with powers limited mainly to the protection of citizens and their property is worth more than its cost to taxpayers because it fosters productive economic activity (not to mention liberty). But additional government spending hinders productive activity in many ways, which are discussed in Daniel Mitchell’s paper, “The Impact of Government Spending on Economic Growth.” (I would add to Mitchell’s list the burden of regulatory activity, which accumulates with the size of government.)

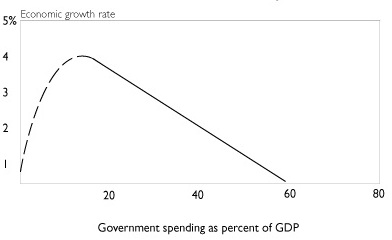

What does the Rahn Curve look like? Daniel Mitchell estimates this relationship between government spending and economic growth:

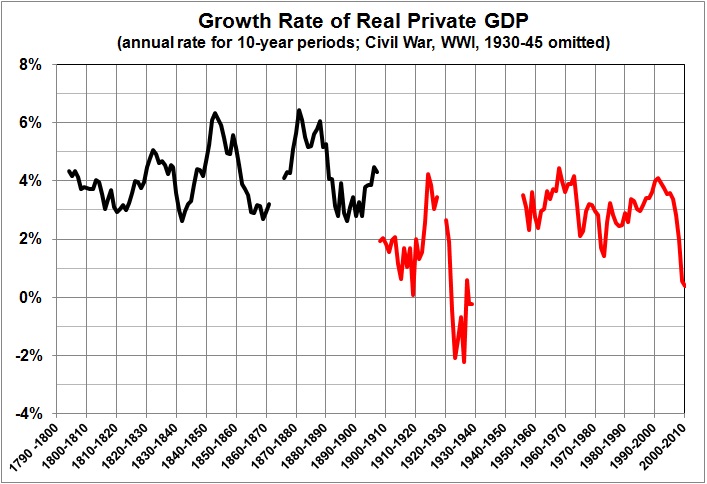

The curve is dashed rather than solid at low values of government spending because it has been decades since the governments of developed nations have spent as little as 20 percent of GDP. But as Mitchell and others note, the combined spending of governments in the U.S. was 10 percent (and less) until the eve of the Great Depression. And it was in the low-spending, laissez-faire era from the end of the Civil War to the early 1900s that the U.S. enjoyed its highest sustained rate of economic growth.

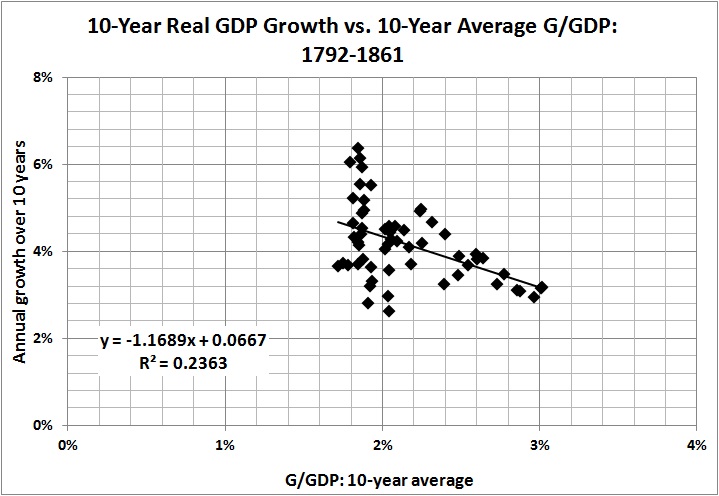

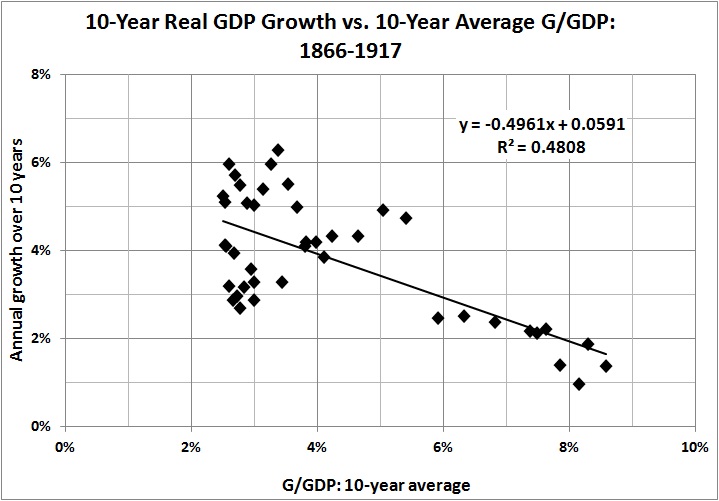

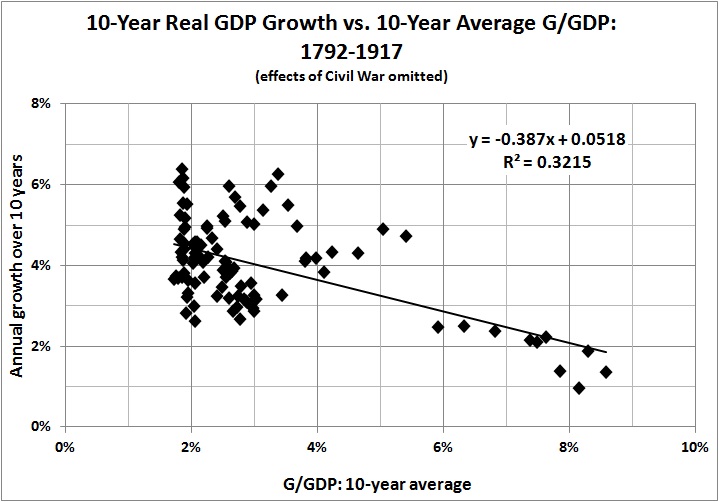

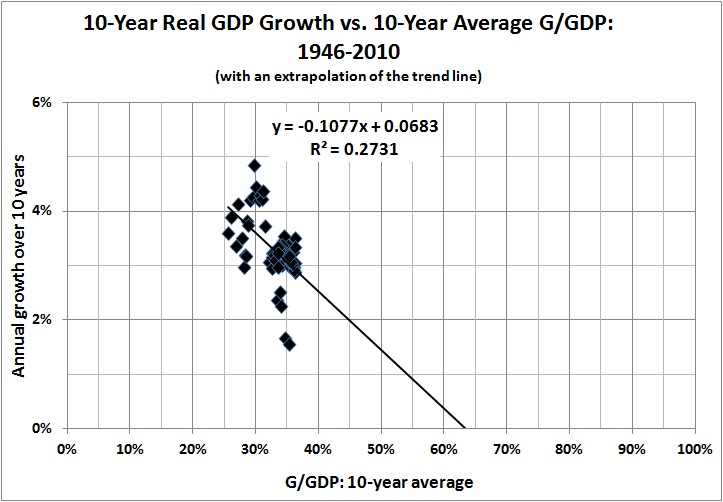

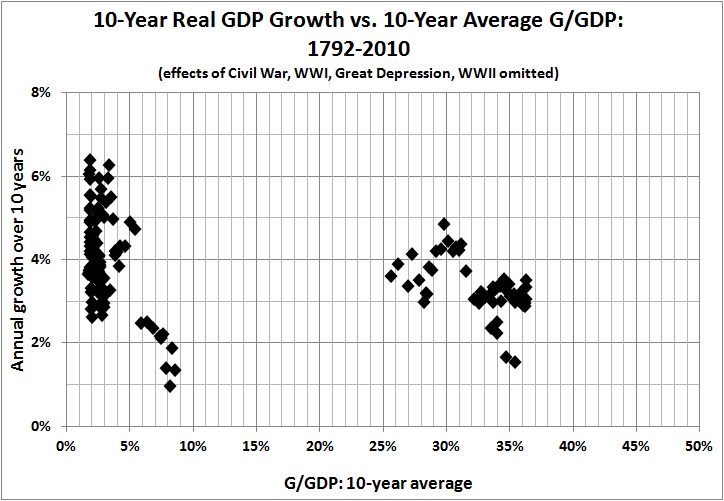

Here is a graphic look at the historical relationship between government spending and GDP growth:

(Source notes for this graph and those that follow are at the bottom of this post.)

The regression lines are there simply to emphasize the long-term trends. The relationship between government spending as a percentage of GDP (G/GDP) and real GDP growth will emerge from the following graphs. There are chronological gaps because the Civil War, WWI, the Great Depression, and WWII distorted the relationship between G/GDP and economic growth. Large wars inflate government spending and GDP. The Great Depression saw a large rise in G/GDP, by pre-Depression standards, even as the economy shrank and then sputtered to a less-than-full recovery before the onset of WWII.

The graphs paint a consistent picture: Higher G/GDP means lower growth. There is one inconsistency, however, and that is the persistence of growth in the range of 2 to 4 percent during the post-WWII era, despite G/GDP in the range of 25-45 percent. That is not the kind of growth one would expect, given the relationships that obtain in the earlier eras. (The extrapolated trend line for 1946-2009 comes into use below.)

There are at least five plausible — and not mutually exclusive — explanations for the discrepancy. First, there is the difficulty of estimating GDP for years long past. Second, it is almost impossible to generate a consistent estimate of real GDP spanning two centuries; current economic output is vastly greater in volume and variety than it was in the early days of the Republic. Third, productivity gains (advances in technology, management techniques, and workers’ skills) may offset the growth-inhibiting effects of government spending, to some extent. Fourth, government regulations and active interventions (e.g., antitrust activity, the income tax) have a cumulative effect that operates independently of G/GDP. Regulations and interventions may have had an especially strong effect in the early 1900s (see the second graph in this post). The effects of regulations and interventions may diminish with time because of adaptive behavior (e.g., “capture” of regulatory bodies).

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there is the shifting composition of government spending. At relatively low levels of G/GDP, G consists largely of government programs that usurp and interfere with private-sector functions by diverting resources from productive uses to uses favored by politicians, bureaucrats, and their patrons. Higher levels of G/GDP — such as those we in the United States have known since the end of WWII — are reached by the expansion of the welfare state. Government spending (at all levels) on so-called social benefits accounted for only 7 percent of G and 0.8 percent of GDP in 1929; in 2009, it accounted for 36 percent of G and 15 percent of GDP. The provision of “social benefits” brings government into the business of redistributing income, which discourages work, saving, and capital formation to some extent, but doesn’t impinge directly on commerce. Therefore, I would expect G to be less damaging to GDP growth at higher levels of G/GDP — which is the message to be found in the contrast between the experience of 1946-2009 and the experience of earlier periods.

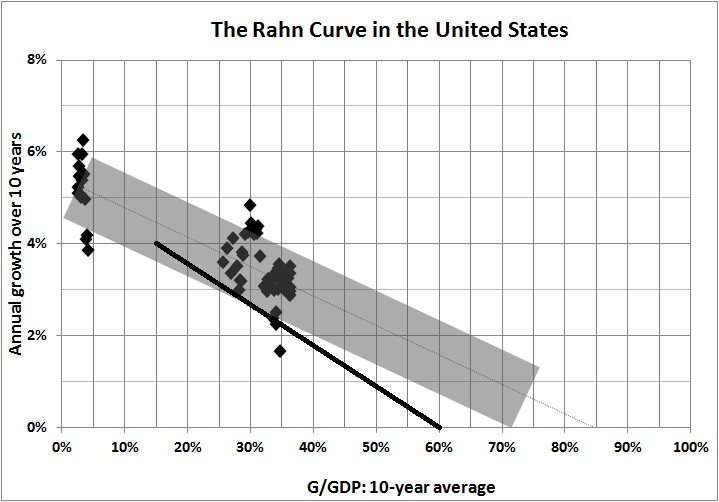

With those thoughts in mind, I present this empirical picture of the relationship between G/GDP and GDP growth in the United States:

The intermediate points, unfortunately, are missing because of the chronological gaps mentioned above. But, as indicated by the five earlier graphs, it is entirely reasonable to infer from the preceding graph a strong relationship between GDP growth and changes in G/GDP throughout the history of the Republic.

It is possible to obtain a rough estimate of the downward sloping portion of the Rahn curve by focusing on two eras: the post-Civil War years 1866-1890 — before the onset of “progressivism,” with its immediate and strong negative effects — and the post-WWII years 1946-2009. Thus:

My rough estimate is appropriately “fuzzy” and somewhat more generous than Daniel Mitchell’s, which is indicated by the heavy black line. In light of my discussion of the shifting composition of G as G/GDP becomes relatively large, I have followed the slope of the trend line for 1792-2010; that is, every 1 percentage-point increase in G/GDP yields a decrease in the growth rate of about 0.07 percent. That seemingly small effect becomes a huge one when G/GDP rises over a long period of time (as has been the case for more than a century, with no end in sight).

For the record, the best fit through the “fuzzy” area is:

Annual rate of growth = -0.066(G/GDP) + 0.054.

[A revised and more realistic estimate for the post-World War II era is

Real rate of growth = -0.372(G/GDP) + 0.067(BA/GDP) + 0.080 ,

where the real rate of growth is the annualized rate over a 10-year period, G/GDP is the fraction of GDP spent by government (including social transfers) over the preceding 10-year period, and BA/GDP represents business assets as a fraction of GDP for the preceding 10-year period.]

Again, it’s the annualized rate of growth over a 10-year span, as a function of G/GDP (fraction of GDP spent by governments at all levels) in the preceding 10 years. The new term, BA/GDP, represents the constant-dollar value of private nonresidential assets (i.e., business assets) as a fraction of GDP, averaged over the preceding 10 years. The idea is to capture the effect of capital accumulation on economic growth, which I didn’t do in the earlier analysis.

Maximum GDP growth seems to occur when G/GDP is 2-4 percent. That is somewhat less than the 7-percent share of GDP that was spent on national defense, public order, and safety in 2010. The excess represents additional “insurance” against predators, foreign and domestic. (The effectiveness of the additional “insurance” is a separate question, though I am inclined to err on the side of caution when it comes to defense and law enforcement. Those functions are not responsible for the economic woes facing America’s taxpayers.)

If G/GDP reaches 55 percent — which it will if present entitlement “commitments” are not curtailed — the “baseline” rate of growth will shrink further: probably to less than 2 percent. And thus America will remain mired in its Mega-Depression.

* * *

Source notes:

Estimates of real and nominal GDP, back to 1790, come from the feature “What Was the U.S GDP Then?” at MeasuringWorth.com.

Estimates of government spending (federal, State, and local) come from USgovernmentspending.com; Statistical Abstracts of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970: Part 2. Series Y 533-566. Federal, State, and Local Government Expenditures, by Function; and the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), Table 3.1. Government Current Receipts and Expenditures (lines 34, 35).

I found the amount spent by governments (federal, State, and local) on national defense and public order and safety by consulting BEA Table 3.17. Selected Government Current and Capital Expenditures by Function.

The BEA tables cited above are available here.

* * *

ADDENDUM: THE RAHN CURVE: A SEQUEL

In the original post (above) I note that maximum GDP growth occurs when government spends two to four percent of GDP. The two-to-four percent range represents the share of GDP claimed by American governments (federal, State, and local) throughout most of the 19th century, when government spending exceeded five percent of GDP only during the Civil War.

Of course, until the early part of the 20th century, when Progressivism began to make itself felt in Americans’ tax bills, governments restricted themselves (in the main) to the functions of national defense, public order, and safety — the terms used in national-income accounting. It is those functions — hereinafter called defense and justice — that foster liberty and economic growth because they protect peaceful, voluntary activity. Effective protection probably would cost more than four percent of GDP in these parlous times. But an adequate figure, except in the rare event of a major war, is probably no more than seven percent of GDP — the value for 2010, which includes the cost of fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In any event, government spending — even on defense and justice — is impossible without private economic activity. It is that activity which yields the wherewithal for the provision of defense and justice. Once those things have been provided, the further diversion of resources by government is economically destructive. Specifically, from “Estimating the Rahn Curve” (above):

It is possible to obtain a rough estimate of the downward sloping portion of the Rahn curve by focusing on two eras: the post-Civil War years 1866-1890 — before the onset of “progressivism,” with its immediate and strong negative effects — and the post-WWII years 1946-2009. Thus:

My rough estimate is appropriately “fuzzy” and somewhat more generous than Daniel Mitchell’s [in “The Impact of Government Spending on Economic Growth”], which is indicated by the heavy black line. In light of my discussion of the shifting composition of G as G/GDP becomes relatively large, I have followed the slope of the trend line for 1792-2010; that is, every 1 percentage-point increase in G/GDP yields a decrease in the growth rate of about 0.06 percent. That seemingly small effect becomes a huge one when G/GDP rises over a long period of time (as has been the case for more than a century, with no end in sight).

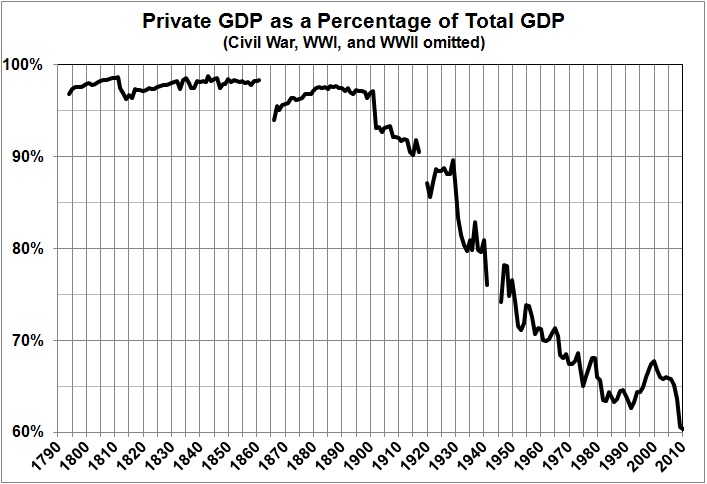

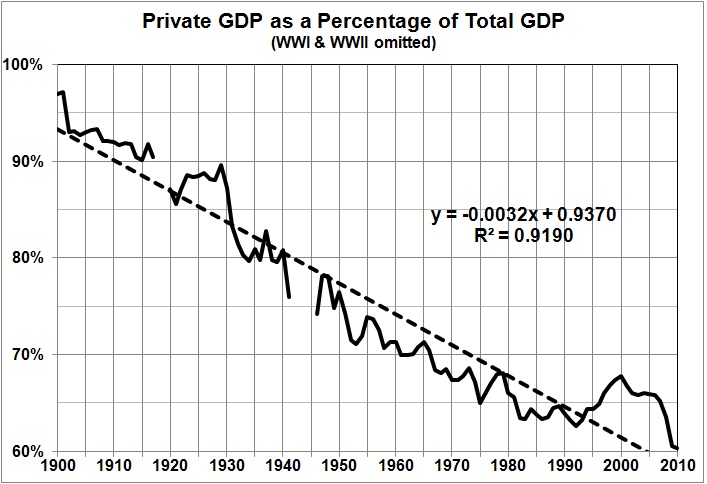

The following graphs offer another view of the devastation wrought by the growth of government spending — and regulation. (Sources are given in “Estimating the Rahn Curve.”) I begin with the share of GDP which is not spent by government:

A note about my measure of government spending is in order. National-income accounting purists would insist that transfer payments (mainly Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid) should not count as spending, even though I count them as such. But what does it matter whether money is taken from taxpayers and given to retired persons (as Social Security) or to government employees (as salary and benefits) or contractors (as reimbursement for products and services delivered to government)? All government spending represents the transfer of claims on resources from persons who earned those claims to other persons, who either did something of questionable value for the money (government employees and contractors) or nothing (e.g., retirees).

In any event, it is obvious that Americans enjoyed minimal government until the early 1900s, and have since “enjoyed” a vast expansion of government. Here is a closer look at the trend from 1900 onward:

This is a good point at which to note that the expansion of government is understated by the growth of government spending, which only imperfectly captures the effects of the rapidly growing regulatory burden on America’s economy. The combined effects of government spending and regulation can be seen in this “before” and “after” depiction of growth rates:

(I omitted the major wars and the Great Depression because their inclusion would give an exaggerated view of economic growth in the aftermath of abnormally suppressed private economic activity.)

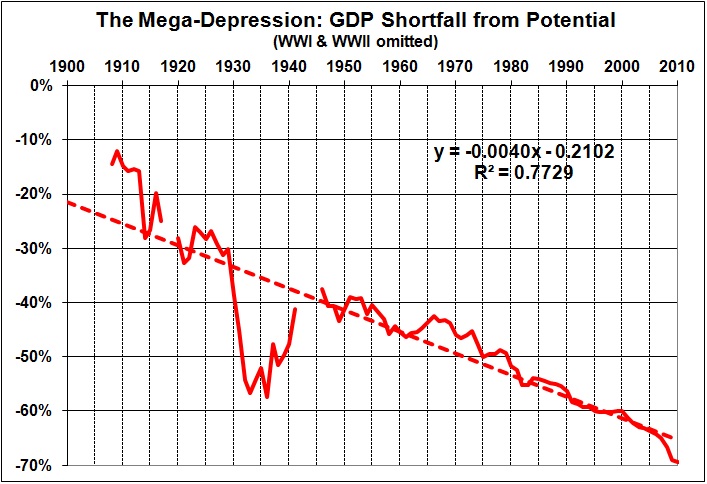

The marked diminution of growth after 1900 has led to what I call America’s Mega-Depression. Note the similarity between the downward path of private sector GDP (two graphs earlier) and the downward path of the Mega-Depression in the following graph:

What is the Mega-Depression? It is a measure of the degree to which real GDP has fallen below what it would have been had economic growth continued at its post-Civil War pace. As I explain here, the Mega-Depression began in the early 1900s, when the economy began to sag under the weight of Progressivism (e.g., trust-busting, regulation, the income tax, the Fed). Then came the New Deal, whose interventions provoked and prolonged the Great Depression (see, for example, this, and this). From the New Deal and the Great Society arose the massive anti-market/initiative-draining/dependency-promoting schemes known as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid. The extension and expansion of those and other intrusive government programs has continued unto the present day (e.g., Obamacare), with the result that our lives and livelihoods are hemmed in by mountains of regulatory restrictions.

Regulation aside, government spending — except for defense and justice — is counterproductive. Not only does it fail to stimulate the economy in the short run, but it also robs the economy of the investments that are needed for long-run growth.

* * *

ADDENDUM: MORE EVIDENCE FOR THE RAHN CURVE

Here:

[W]e have some new research from the United Kingdom. The Centre for Policy Studies has released a new study, authored by Ryan Bourne and Thomas Oechsle, examining the relationship between economic growth and the size of the public sector.

The chart above compares growth rates for nations with big governments and small governments over the past two decades. The difference is significant, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg. The most important findings of the report are the estimates showing how more spending and more taxes are associated with weaker performance.

Here are some key passages from the study.

Using tax to GDP and spending to GDP ratios as a proxy for size of government, regression analysis can be used to estimate the effect of government size on GDP growth in a set of countries defined as advanced by the IMF between 1965 and 2010. …As supply-side economists would expect, the coefficients on the tax revenue to GDP and government spending to GDP ratios are negative and statistically significant. This suggests that, ceteris paribus, a larger tax burden results in a slower annual growth of real GDP per capita. Though it is unlikely that this effect would be linear (we might expect the effect to be larger for countries with huge tax burdens), the regressions suggest that an increase in the tax revenue to GDP ratio by 10 percentage points will, if the other variables do not change, lead to a decrease in the rate of economic growth per capita by 1.2 percentage points. The result is very similar for government outlays to GDP, where an increase by 10 percentage points is associated with a fall in the economic growth rate of 1.1 percentage points. This is in line with other findings in the academic literature. …The two small government economies with the lowest marginal tax rates, Singapore and Hong Kong, were also those which experienced the fastest average real GDP growth.

My own estimate (see above) for the United States, is that

every 1 percentage-point increase in G/GDP yields a decrease in the growth rate of about 0.07 percent. That seemingly small effect becomes a huge one when G/GDP rises over a long period of time (as has been the case for more than a century, with no end in sight).

In other words, every 10 percentage-point increase in the ratio of government spending to GDP causes a not-insignificant drop of 0.7 percentage points in the rate of growth. That is somewhat below the estimate quoted above (1.1 percentage points), but surely it is within the range of uncertainty that surrounds the estimate.