The typology of personality is a fascinating but superficial way of looking at human nature and the sources of conflict among human beings. I will begin there before probing more deeply. If you are eager to get to the bottom line of this post, scroll down to “Conflict”.

SOME ASPECTS OF PERSONALITY

Generaloberst Kurt Gebhard Adolf Philipp Freiherr von Hammerstein-Equord (1878-1943) was commendable for at least two reasons. He was outspokenly against the Nazi regime, and he conceived this classification scheme for officers:

I distinguish four types. There are clever, hardworking, stupid, and lazy officers. Usually two characteristics are combined. Some are clever and hardworking; their place is the General Staff. The next ones are stupid and lazy; they make up 90 percent of every army and are suited to routine duties. Anyone who is both clever and lazy is qualified for the highest leadership duties, because he possesses the mental clarity and strength of nerve necessary for difficult decisions. One must beware of anyone who is both stupid and hardworking; he must not be entrusted with any responsibility because he will always only cause damage.

Here is my paraphrase of that scheme:

- Smart and hard-working (good middle manager)

- Stupid and lazy (lots of these around, hire for simple, routine tasks and watch closely)

- Smart and lazy (promote to senior management — delegates routine work and keeps his eye on the main prize)

- Stupid and hard-working (dangerous to have around, screws up things, should be taken out and shot). (This describes the boss whose “leadership” skills prompted me to retire early.)

Personality analysis and classification has since become an industry. It provides pseudo-scientific insights for the misuse of corporate executives and HR departments. And it offers endless hours of enjoyment (and self-doubt and argument) for casual users.

For my own part, I have taken the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) several times since the late 1980s. It is in ill repute, but I have always found it to be reliable, especially in my own case. I am an INTJ, which is I(ntroverted), (i)N(tuitive), T(hinking), J(udging):

For INTJs the dominant force in their lives is their attention to the inner world of possibilities, symbols, abstractions, images, and thoughts. Insight in conjunction with logical analysis is the essence of their approach to the world; they think systemically. Ideas are the substance of life for INTJs and they have a driving need to understand, to know, and to demonstrate competence in their areas of interest. INTJs inherently trust their insights, and with their task-orientation will work intensely to make their visions into realities. (Source: “The Sixteen Types at a Glance“.)

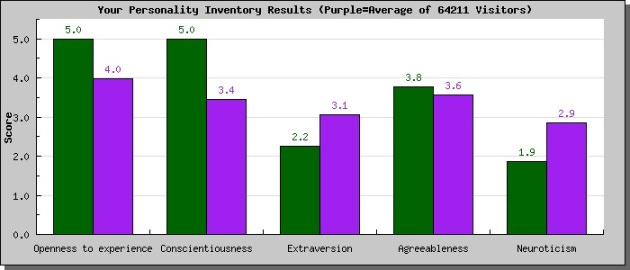

I first took the “Big 5” personality test in 2009, with this result (details here):

My scores are in green; the average scores of all other test-takers are in purple. The five traits are defined as follows:

1. Openness to experience: High scorers are described as “Open to new experiences. You have broad interests and are very imaginative.” Low scorers are described as “Down-to-earth, practical, traditional, and pretty much set in your ways.” This is the sub-scale that shows the strongest relationship to politics: liberals generally score high on this trait; they like change and variety, sometimes just for the sake of change and variety. Conservatives generally score lower on this trait. (Just think about the kinds of foods likely to be served at very liberal or very conservative social events.)

2. Conscientiousness: High scorers are described as “conscientious and well organized. They have high standards and always strive to achieve their goals. They sometimes seem uptight. Low scorers are easy going, not very well organized and sometimes rather careless. They prefer not to make plans if they can help it.”

3. Extraversion: High scorers are described as “Extraverted, outgoing, active, and high-spirited. You prefer to be around people most of the time.” Low scorers are described as “Introverted, reserved, and serious. You prefer to be alone or with a few close friends.” Extraverts are, on average, happier than introverts.

4. Agreeableness: High scorers are described as “Compassionate, good-natured, and eager to cooperate and avoid conflict.” Low scorers are described as “Hardheaded, skeptical, proud, and competitive. You tend to express your anger directly.”

5. Neuroticism: High scorers are described as “Sensitive, emotional, and prone to experience feelings that are upsetting.” Low scorers are described as “Secure, hardy, and generally relaxed even under stressful conditions.”

Dozens more such tests (many of which I have taken) are available. Some of them can be found at yourmorals.org (free signup).

Personality differences occasion conflict, of course. For example, decisive persons are often frustrated by and impatient with indecisive ones (and vice versa), and extroverts usually don’t understand introverts and the advantages of introversion (e.g., introspection, thinking more deeply about problems).

HUMAN NATURE WRIT LARGER

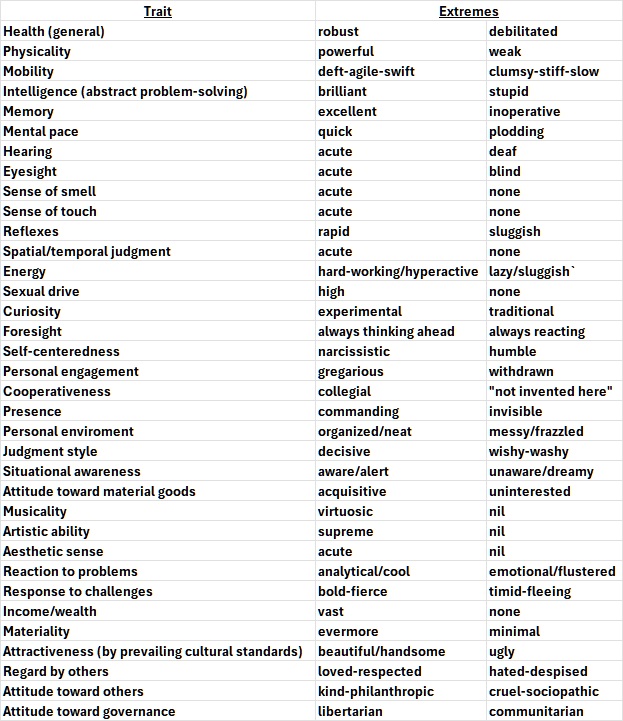

But personality tests only scratch the surface of human nature and differences among human beings. Consider the following 35 traits:

You can add to that list, I’m sure. But let’s consider the implications of the 35-trait scale for differentiating among human beings.

If each trait were quantified on a scale from 1 to 10 (though the actual range for most traits is infinite) the number of possible combinations would approach 3 quadrillion. That’s more than 300 times the number of human beings now living on Earth. To say that every human being is unique is a vast understatement.

And yet — despite the unquantifiable complexity of human beings — there is a tendency to love, like, admire, dislike, or detest a person because he or she possesses a particular trait or two — or because one is anxious to be “in” with a person or group who loves, likes, etc., because of a trait or two. Even more ephemerally, love, like, etc., be triggered when a person simply says something that suggests a particular opinion or attitude.

These tendencies seem to have been around for a long time — for as long as there have been human beings, and even longer. Fear and ferocity are easily triggered in many species of animals. This suggests that making snap judgements about other persons is an inbred survival mechanism that evolution and socialization couldn’t eradicate and may have reinforced. (Evolution has somehow become thought of as a kind of progress, but it is nothing more than unplanned change caused by external stimuli and random mutations. The belief that evolution represents progress is akin to the anthropic principle.)

Some of the prominent triggers nowadays (e.g., certain political opinions or positions) may be new. But their newness only suggests that the tendency to form snap judgements has found new outlets in keeping with cultural change. In addition to reacting fiercely to perceived threats to life and limb, humans acquired the trait of reacting vociferously (and sometimes fiercely) to perceived threats to their self-image, of which beliefs constitute an essential part.

That isn’t new, either. Nor is the perception new that the actualization of certain beliefs (or dogmas) about such matters as race, religion, government, economics, justice, sex, and morality would result in misery because they would lead to oppression, aggression, economic disaster, social division, or any combination of those things. The correctness of that perception carries the weight of historical evidence, which matters to those who are swayed by reality and not by fairytales.

Today’s divisions about race, religion, government, economics, justice, sex, and morality are just replays of eons-old conflicts along the same lines. They are replays because human nature is immutable. The only thing that changes are the manifestations of human nature in action.

Those who do not grasp human nature in its fullness — the bad with the good — are doomed to be surprised by the consequences of the actualization of their beliefs. Or they would be surprised if the human capacity for self-delusion didn’t blind them to those consequences.

Leftists and “intellectuals” (nearly identical categories) are especially prone to misjudging the consequences of their beliefs because they have spun themselves delusional fairytales about the rightness of their beliefs. I don’t need to (and won’t) relate the fairytales about race, religion, government, economics, justice, sex, and morality. All of those (and more) are amply addressed in this blog (go here and explore) and in the many other reality-based blogs and journals that abound on the internet.

CONFLICT

Here, I will focus on a fairytale about conflict itself. It is the subject of another long post of mine, from eleven years ago, “The Fallacy of Human Progress“. I won’t reproduce it or quote it at length. I can only urge you to read it.

I will conclude this post with a few of the main points from that one. It was inspired by Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (2011). I can only say the events of the past thirteen years — and especially of the past few years in Ukraine, Israel, and America (to name only a few places) — are proof that Pinker was dead wrong.

The best refutation of Pinker’s thesis that I have read is by John Gray, an English philosopher, in his book The Silence of Animals: On Progress and Other Modern Myths. Gray’s book appeared only eighteen months after Pinker’s and doesn’t mention Pinker or his book. The refutation is therefore only implicit, but just as powerful as if it were aimed directly at Pinker’s book.

Gray’s argument is faithfully recounted in a review of his book by Robert W. Merry at The National Interest:

The noted British historian J. B. Bury (1861–1927) . . . wrote, “This doctrine of the possibility of indefinitely moulding the characters of men by laws and institutions . . . laid a foundation on which the theory of the perfectibility of humanity could be raised. It marked, therefore, an important stage in the development of the doctrine of Progress.”

We must pause here over this doctrine of progress. It may be the most powerful idea ever conceived in Western thought…. It is the thesis that mankind has advanced slowly but inexorably over the centuries from a state of cultural backwardness, blindness and folly to ever more elevated stages of enlightenment and civilization—and that this human progression will continue indefinitely into the future . . . . The U.S. historian Charles A. Beard once wrote that the emergence of the progress idea constituted “a discovery as important as the human mind has ever made, with implications for mankind that almost transcend imagination.” And Bury, who wrote a book on the subject, called it “the great transforming conception, which enables history to define her scope.”

Gray rejects it utterly. In doing so, he rejects all of modern liberal humanism. “The evidence of science and history,” he writes, “is that humans are only ever partly and intermittently rational, but for modern humanists the solution is simple: human beings must in future be more reasonable. These enthusiasts for reason have not noticed that the idea that humans may one day be more rational requires a greater leap of faith than anything in religion.” In an earlier work, Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals, he was more blunt: “Outside of science, progress is simply a myth.”

. . . Gray has produced more than twenty books demonstrating an expansive intellectual range, a penchant for controversy, acuity of analysis and a certain political clairvoyance.

He rejected, for example, Francis Fukuyama’s heralded “End of History” thesis—that Western liberal democracy represents the final form of human governance—when it appeared in this magazine in 1989. History, it turned out, lingered long enough to prove Gray right and Fukuyama wrong….

Though for decades his reputation was confined largely to intellectual circles, Gray’s public profile rose significantly with the 2002 publication of Straw Dogs, which sold impressively and brought him much wider acclaim than he had known before. The book was a concerted and extensive assault on the idea of progress and its philosophical offspring, secular humanism. The Silence of Animals is in many ways a sequel, plowing much the same philosophical ground but expanding the cultivation into contiguous territory mostly related to how mankind—and individual humans—might successfully grapple with the loss of both metaphysical religion of yesteryear and today’s secular humanism. The fundamentals of Gray’s critique of progress are firmly established in both books and can be enumerated in summary.

First, the idea of progress is merely a secular religion, and not a particularly meaningful one at that. “Today,” writes Gray in Straw Dogs, “liberal humanism has the pervasive power that was once possessed by revealed religion. Humanists like to think they have a rational view of the world; but their core belief in progress is a superstition, further from the truth about the human animal than any of the world’s religions.”

Second, the underlying problem with this humanist impulse is that it is based upon an entirely false view of human nature—which, contrary to the humanist insistence that it is malleable, is immutable and impervious to environmental forces. Indeed, it is the only constant in politics and history. Of course, progress in scientific inquiry and in resulting human comfort is a fact of life, worth recognition and applause. But it does not change the nature of man, any more than it changes the nature of dogs or birds. “Technical progress,” writes Gray, again in Straw Dogs, “leaves only one problem unsolved: the frailty of human nature. Unfortunately that problem is insoluble.”

That’s because, third, the underlying nature of humans is bred into the species, just as the traits of all other animals are. The most basic trait is the instinct for survival, which is placed on hold when humans are able to live under a veneer of civilization. But it is never far from the surface. In The Silence of Animals, Gray discusses the writings of Curzio Malaparte, a man of letters and action who found himself in Naples in 1944, shortly after the liberation. There he witnessed a struggle for life that was gruesome and searing. “It is a humiliating, horrible thing, a shameful necessity, a fight for life,” wrote Malaparte. “Only for life. Only to save one’s skin.” Gray elaborates:

Observing the struggle for life in the city, Malaparte watched as civilization gave way. The people the inhabitants had imagined themselves to be—shaped, however imperfectly, by ideas of right and wrong—disappeared. What were left were hungry animals, ready to do anything to go on living; but not animals of the kind that innocently kill and die in forests and jungles. Lacking a self-image of the sort humans cherish, other animals are content to be what they are. For human beings the struggle for survival is a struggle against themselves.

When civilization is stripped away, the raw animal emerges. “Darwin showed that humans are like other animals,” writes Gray in Straw Dogs, expressing in this instance only a partial truth. Humans are different in a crucial respect, captured by Gray himself when he notes that Homo sapiens inevitably struggle with themselves when forced to fight for survival. No other species does that, just as no other species has such a range of spirit, from nobility to degradation, or such a need to ponder the moral implications as it fluctuates from one to the other. But, whatever human nature is—with all of its capacity for folly, capriciousness and evil as well as virtue, magnanimity and high-mindedness—it is embedded in the species through evolution and not subject to manipulation by man-made institutions.

Fourth, the power of the progress idea stems in part from the fact that it derives from a fundamental Christian doctrine—the idea of providence, of redemption . . . .

“By creating the expectation of a radical alteration in human affairs,” writes Gray, “Christianity . . . founded the modern world.” But the modern world retained a powerful philosophical outlook from the classical world—the Socratic faith in reason, the idea that truth will make us free; or, as Gray puts it, the “myth that human beings can use their minds to lift themselves out of the natural world.” Thus did a fundamental change emerge in what was hoped of the future. And, as the power of Christian faith ebbed, along with its idea of providence, the idea of progress, tied to the Socratic myth, emerged to fill the gap. “Many transmutations were needed before the Christian story could renew itself as the myth of progress,” Gray explains. “But from being a succession of cycles like the seasons, history came to be seen as a story of redemption and salvation, and in modern times salvation became identified with the increase of knowledge and power.”

Thus, it isn’t surprising that today’s Western man should cling so tenaciously to his faith in progress as a secular version of redemption. As Gray writes, “Among contemporary atheists, disbelief in progress is a type of blasphemy. Pointing to the flaws of the human animal has become an act of sacrilege.” In one of his more brutal passages, he adds:

Humanists believe that humanity improves along with the growth of knowledge, but the belief that the increase of knowledge goes with advances in civilization is an act of faith. They see the realization of human potential as the goal of history, when rational inquiry shows history to have no goal. They exalt nature, while insisting that humankind—an accident of nature—can overcome the natural limits that shape the lives of other animals. Plainly absurd, this nonsense gives meaning to the lives of people who believe they have left all myths behind.

In the Silence of Animals, Gray explores all this through the works of various writers and thinkers. In the process, he employs history and literature to puncture the conceits of those who cling to the progress idea and the humanist view of human nature. Those conceits, it turns out, are easily punctured when subjected to Gray’s withering scrutiny . . . .

And yet the myth of progress is so powerful in part because it gives meaning to modern Westerners struggling, in an irreligious era, to place themselves in a philosophical framework larger than just themselves . . . .

Much of the human folly catalogued by Gray in The Silence of Animals makes a mockery of the earnest idealism of those who later shaped and molded and proselytized humanist thinking into today’s predominant Western civic philosophy.

There was an era of realism, but it was short-lived:

But other Western philosophers, particularly in the realm of Anglo-Saxon thought, viewed the idea of progress in much more limited terms. They rejected the idea that institutions could reshape mankind and usher in a golden era of peace and happiness. As Bury writes, “The general tendency of British thought was to see salvation in the stability of existing institutions, and to regard change with suspicion.” With John Locke, these thinkers restricted the proper role of government to the need to preserve order, protect life and property, and maintain conditions in which men might pursue their own legitimate aims. No zeal here to refashion human nature or remake society.

A leading light in this category of thinking was Edmund Burke (1729–1797), the British statesman and philosopher who, writing in his famous Reflections on the Revolution in France, characterized the bloody events of the Terror as “the sad but instructive monuments of rash and ignorant counsel in time of profound peace.” He saw them, in other words, as reflecting an abstractionist outlook that lacked any true understanding of human nature. The same skepticism toward the French model was shared by many of the Founding Fathers, who believed with Burke that human nature isn’t malleable but rather potentially harmful to society. Hence, it needed to be checked. The central distinction between the American and French revolutions, in the view of conservative writer Russell Kirk, was that the Americans generally held a “biblical view of man and his bent toward sin,” whereas the French opted for “an optimistic doctrine of human goodness.” Thus, the American governing model emerged as a secular covenant “designed to restrain the human tendencies toward violence and fraud . . . [and] place checks upon will and appetite.”

Most of the American Founders rejected the French philosophes in favor of the thought and history of the Roman Republic, where there was no idea of progress akin to the current Western version. “Two thousand years later,” writes Kirk, “the reputation of the Roman constitution remained so high that the framers of the American constitution would emulate the Roman model as best they could.” They divided government powers among men and institutions and created various checks and balances. Even the American presidency was modeled generally on the Roman consular imperium, and the American Senate bears similarities to the Roman version. Thus did the American Founders deviate from the French abstractionists and craft governmental structures to fit humankind as it actually is—capable of great and noble acts, but also of slipping into vice and treachery when unchecked. That ultimately was the genius of the American system.

But, as the American success story unfolded, a new collection of Western intellectuals, theorists and utopians—including many Americans—continued to toy with the idea of progress. And an interesting development occurred. After centuries of intellectual effort aimed at developing the idea of progress as an ongoing chain of improvement with no perceived end into the future, this new breed of “Progress as Power” thinkers began to declare their own visions as the final end point of this long progression.

Gray calls these intellectuals “ichthyophils,” which he defines as “devoted to their species as they think it ought to be, not as it actually is or as it truly wants to be.” He elaborates: “Ichthyophils come in many varieties—the Jacobin, Bolshevik and Maoist, terrorizing humankind in order to remake it on a new model; the neo-conservative, waging perpetual war as a means to universal democracy; liberal crusaders for human rights, who are convinced that all the world longs to become as they imagine themselves to be.” He includes also “the Romantics, who believe human individuality is everywhere repressed.”

Throughout American politics, as indeed throughout Western politics, a large proportion of major controversies ultimately are battles between the ichthyophils and the Burkeans, between the sensibility of the French Revolution and the sensibility of American Revolution, between adherents of the idea of progress and those skeptical of that potent concept. John Gray has provided a major service in probing with such clarity and acuity the impulses, thinking and aims of those on the ichthyophil side of that great divide. As he sums up, “Allowing the majority of humankind to imagine they are flying fish even as they pass their lives under the waves, liberal civilization rests on a dream.”

Amen.

These somewhat related posts may be of interest to you: “Evolution, Human Nature, and ‘Natural Rights’“, “More Thoughts about Evolutionary Teleology“, and “Scientism, Evolution, and the Meaning of Life“.