The widespread use of steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs) in recent decades probably led to an increase in extra-base hits. But, paradoxically, the emphasis on power hitting may have led to a decrease in run production. Or maybe not.

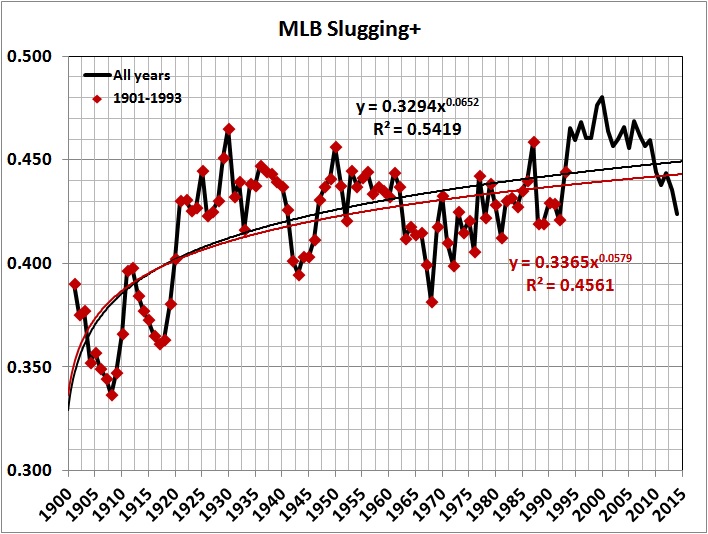

I begin with a statistic that I call Slugging+ (abbreviated as SLG+). It measures total bases on hits and walks per plate appearance:

(1) SLG+ = [1B + 2B(2) + 3B(3) + HR(4) + BB]/PA

where,

1B = singles

2B = doubles

3B = triples

HR = home runs

BB = bases-on-balls (walks)

PA = plate appearances

(I prefer SLG+ to OPS — a popular statistic that combines on-base-average and slugging percentage. OPS is the sum of two fractions with different denominators, PA and AB (at-bats), and it double-counts hits, which are in the numerator of both fractions.)

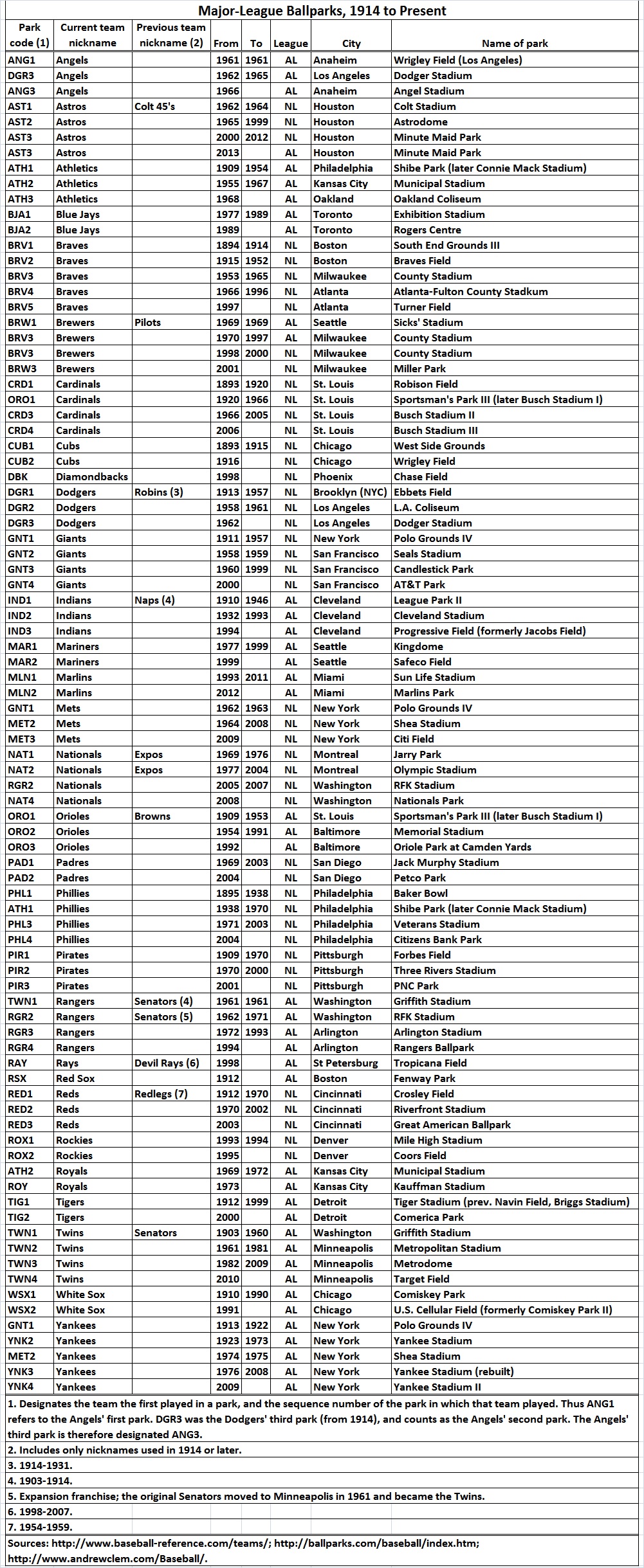

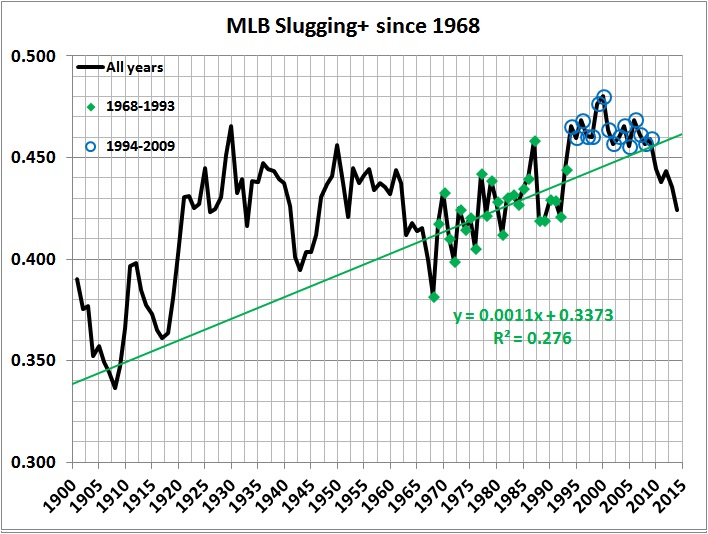

The following graph of SLG+ is suggestive:

The values of SLG+ after 1993 — and especially for the years 1994-2009 — boost the regression line markedly upward.

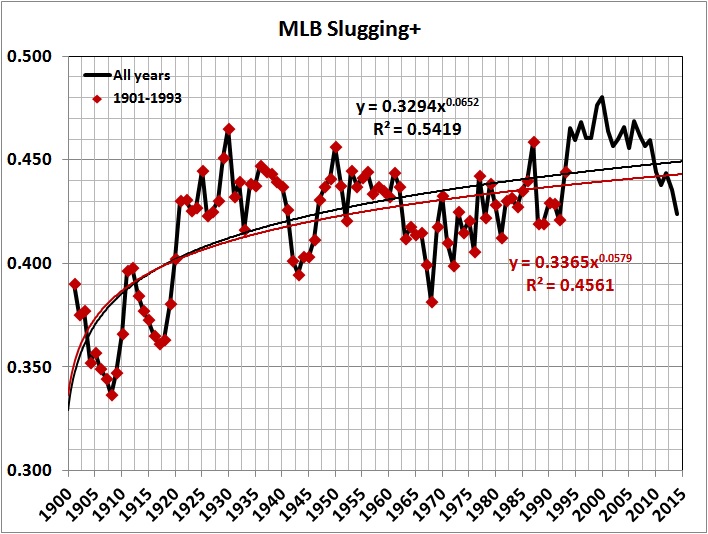

A similar picture emerges in the next graph, which focuses on the years after 1968, when offensive statistics reached a nadir:

SLG+ values for 1994-2009 lie above the trend line.

On the evidence of the two preceding graphs I designate 1994-2009 as the era of PEDs. (I know that PEDs didn’t come into use in 1994 and disappear from the scene after 2009. It’s just that their effects are most obvious during 1994-2009.)

So much for the effect of PEDs on power hitting. What about the effect of PEDs on run production? You might expect that the unsurpassed surge in power hitting during the PEDs era resulted in an unsurpassed surge in run production: But it didn’t:

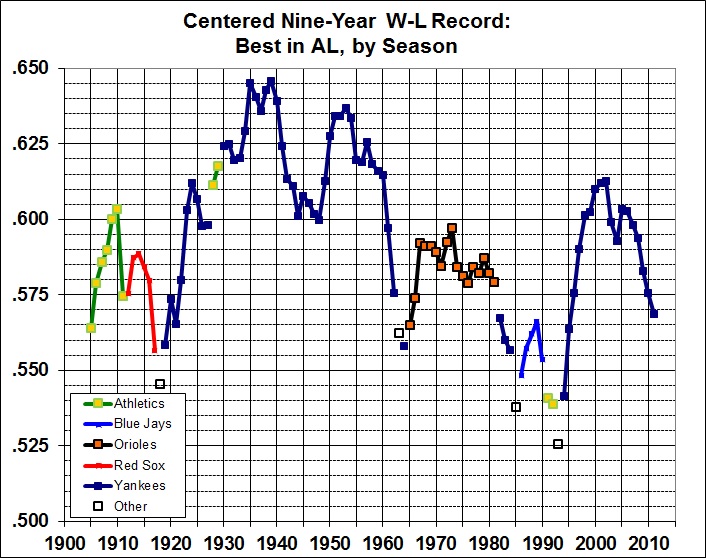

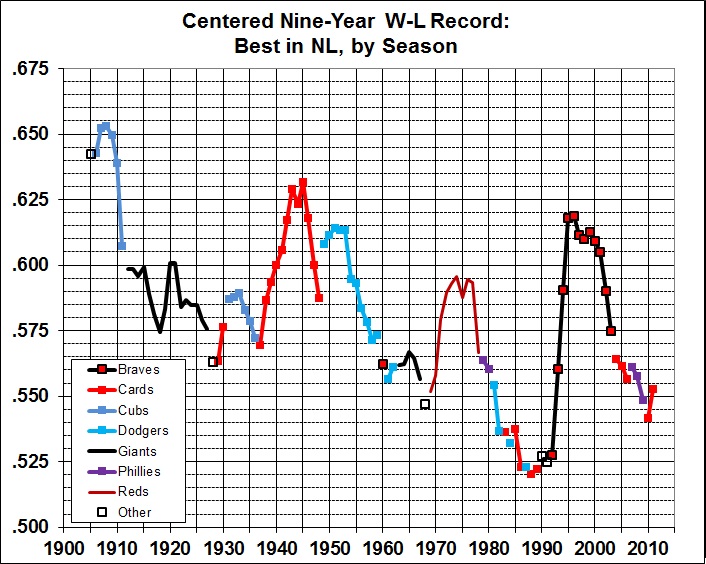

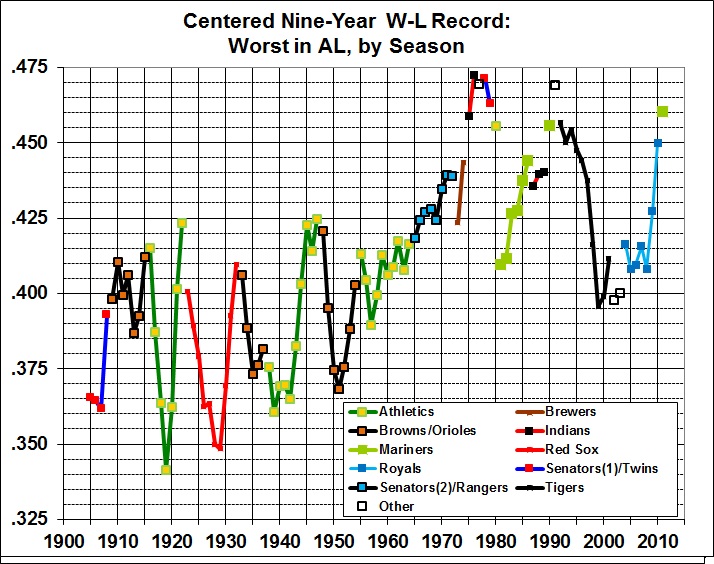

Why did run production in the PEDs era fall short of run production in 1921-1942, the original “lively ball” era. Here’s my hypothesis: The frequency of home runs was on the rise during the original “lively ball” era. But the game in that era was still strongly influenced by the dynamic style of play of the preceding “dead ball” era. Scoring in the lively-ball era still depended heavily on slapping out base hits, taking the extra base on an outfield hit, and the hit-and-run. Those practices dwindled in later years, when scoring became more a matter of waiting for sluggers to deliver home runs, when they weren’t drawing walks or striking out. Some of the differences are evident in this graph:

It turns out that the emphasis on power hitting (especially home-run hitting) may be counterproductive. The relationship between runs per game (R) and other significant variables for the period 1921-2014 looks like this:

(2) R = – 0.220 + 18.7(BA) + 0.721(2B) + 1.26(HR) – 0.160(SO) – 0.0540(BatAge)

where,

BA = batting average

2B = doubles per game

HR = home runs per game

SO = strikeouts per game

BatAge = average age of batters

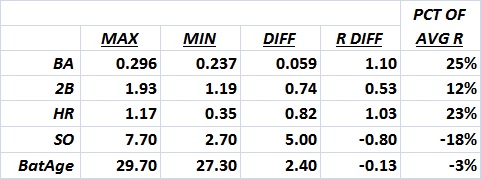

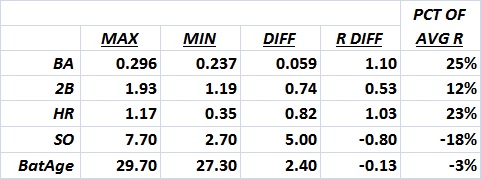

Applying (2) to the actual range of values for each variable, I get:

“Max” and “min” are the maximum and minimum values for 1921-2014. “Diff” is the difference between the maximum and minimum values. “R diff” represents the number of runs accounted for by “Diff,” based on equation (2). “Pct. of avg. R” is “R diff” as a percentage of the average number of runs per game during 1921-2014.

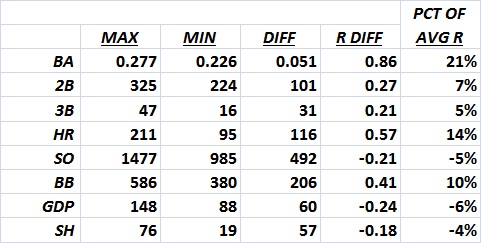

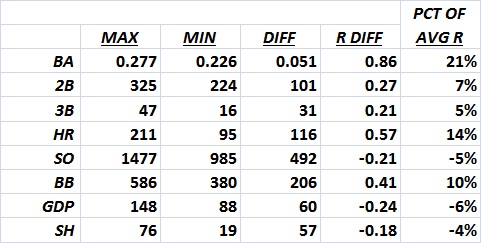

Team statistics for 2014 yield a somewhat more detailed but similar result:

(3) R = – 0.153 + 16.8(BA) + 0.00269(2B) + 0.00675(3B) + 0.00488(HR) – 0.000428(SO) + 0.00198(BB) – 0.00408(GDP) – 0.00314(SH)

where,

BA = team batting average

2B = doubles hit by team

3B = triples hit by team

HR = home runs hit by team

SO = team strikeouts

BB = team walks

GDP = number of times a team grounds into double plays

SH = number of times a team executes a sacrifice hit (a bunt that advances a base runner)

Applying (3) to the actual range of values for each variable, I get:

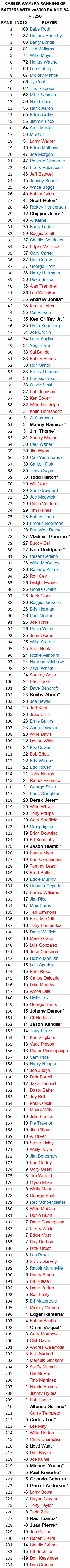

For a third look, I analyzed the offensive records of the 560 players with at least 3,000 plate appearances whose careers started no sooner than 1946 and ended no later than 1993. I computed, for each player, a measure of his career run-scoring potential (R*):

(4) R* = [(1B + 2(2B) + 3(3B) + 4(HR) + BB + HBP + SH + SF – GDP + SB – CS]/PA

where,

1B = singles

2B = doubles

3B = triples

HR = home runs

BB = bases on balls

HBP = hit by pitcher

SH = sacrifice hits

SF = sacrifice flies

GDP = grounded into double plays

SB = stolen bases

CS = caught stealing

PA = plate appearances

This regression equation explains R*:

(5) R* = 0.0521 + 0.796(1B) + 1.794(2B) + 3.29 (3B) + 3.68(HR) + 0.998(BB) – 0.0450(SO) + 1.18(SB – CS)

(The explanatory variables are career totals divided by total number of plate appearances. The equation has an r-squared of 0.985, with extremely significant F- and p-values.)

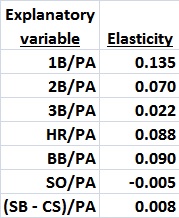

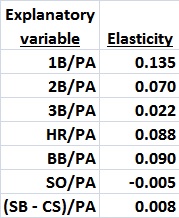

I derived the following table of elasticities from (5):

Elasticity measures the responsiveness of R* to a change in the value of each variable. Thus, for example, a 1-percent increase in 1B/PA would cause R* to increase by 0.135 percent, and so on. The elasticities suggest that singles hitters generate more scoring opportunities than home-run hitters, on the whole. Case closed?

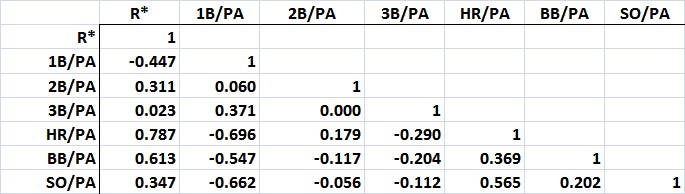

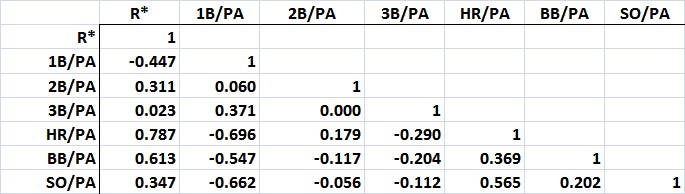

Not at all. Look at this table of cross-correlations:

Even though there’s a strong, positive correlation between HR/PA and SO/PA, the elasticity on SO/PA is relatively small. Further, the elasticity on BB/PA is relatively high, and BB/PA is strongly and negatively correlated with 1B/PA — and less strongly but positively correlated with HR/PA. This leads me to suspect that the elasticities on 1B/PA and HR/PA overstate the contributions of singles hitters and understate the contributions of home-run hitters.

I forced a regression in which the only explanatory variables are 1B, 2B, 3B, and HR. The resulting equation yields these elasticities:

(I obtained similar results when I revisited the statistics for 1921-2014 and the 2014 season.)

This is a less-than-satisfactory result because the underlying equation omits several explanatory variables. But it hints at the value of hitters with extra-base power, especially home-run hitters. Issues of health and integrity aside, it seems that a “juiced” hitter can do his team a lot of good — if he doesn’t strike out a lot more or walk a lot less than usual in his pursuit of more home runs.

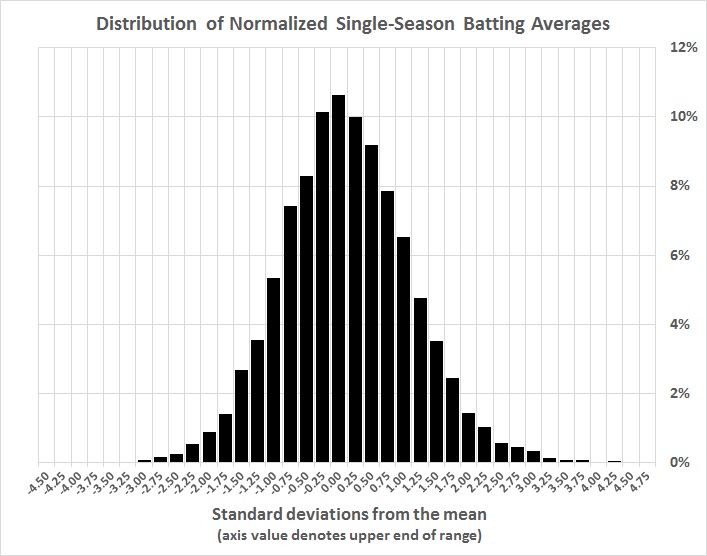

All of this uncertainty reminds me of “Baseball Statistics and the Consumer Price Index,” where I say this:

There are many variations in the conditions of play that have resulted in significant changes in offensive statistics. Among those changes are the use of cleaner and more tightly wound baseballs, the advent of night baseball, better lighting for night games, bigger gloves, lighter bats, bigger and stronger players, the expansion of the major leagues in fits and starts, the size of the strike zone, the height of the pitching mound, and — last but far from least in this list — the integration of black and Hispanic players into major league baseball. In addition to these structural variations, there are others that mitigate against the commensurability of statistics over time; for example, the rise and decline of each player’s skills, the skills of teammates (which can boost or depress a player’s performance), the characteristics of a player’s home ballpark (where players generally play half their games), and the skills of the opposing players who are encountered over the course of a career.

Despite all of these obstacles to commensurability, the urge to evaluate the relative performance of players from different teams, leagues, seasons, and eras is irrepressible. Baseball-Reference.com is rife with such evaluations; the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) revels in them; many books offer them (e.g., this one); and I have succumbed to the urge more than once.

It is one thing to have fun with numbers. It is quite another thing to ascribe meanings to them that they cannot support.

All I can safely say about the effect of PEDs on run-scoring is that the PEDs era saw more of it than the preceding era (see the third graph, “MLB Team Runs per Game”).

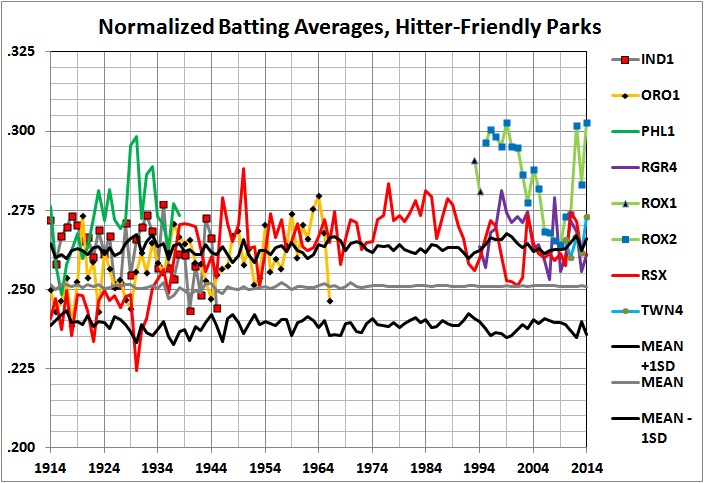

In the end, the seemingly large effect of PEDs may be illusory:

…In congressional testimony in 2005, [Sandy] Alderson [former general manager of the Oakland A’s] said that during the 1990s, other factors “obscured a steroid problem”:

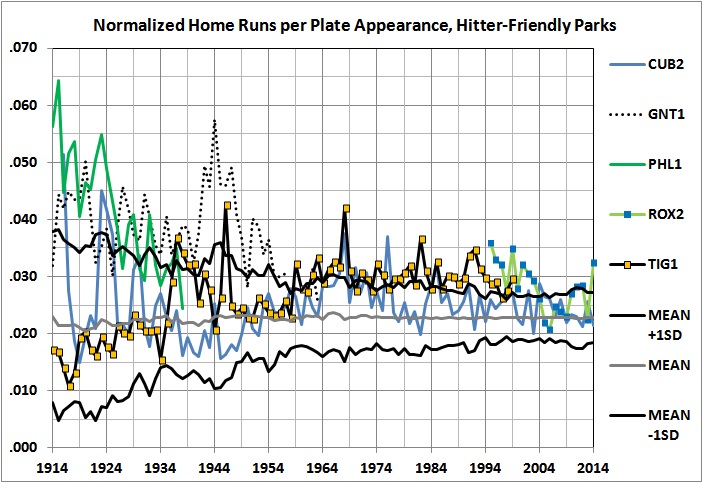

Home runs and run production were increasing during the time but not always year to year. At the same time, strength programs were in vogue across baseball. Hitter-friendly ballparks were being built. Expansion had occurred in 1993 and again in 1998. Two seasons, ’94 and ’95, had been shortened by a players’ strike. Bat design had changed and there was an emphasis with many clubs on having more offensive players even at traditionally defensive positions. [From pp. 62-3 of the Mitchell report, listed in “Related reading.”]

The factors cited by Alderson probably boosted the rate at which batters were pumping out extra-base hits. Another significant factor is the size of the strike zone, which had been shrinking for years before it began to expand around 2009-10. Has power hitting declined because of the growing strike zone or because fewer players are using PEDs? The right answer is “yes.”

Uncertainty rears its head again.

* * *

Acknowledgement: This analysis draws on statistics provided by Baseball-Reference.com.

* * *

Related reading:

Mitchell Grossman et al., “Steroids in Major League Baseball,” undated

Baseball Prospectus, “Baseball between the Numbers: What Do Statistics Tell Us About Steroids?,” March 9, 2006

George J. Mitchell, “Report to the Commissioner of Baseball of an Independent Investigation into the Illegal Use of Steroids and Other Performance Enhancing Substances by Players in Major League Baseball,” December 13, 2007

Zachary D. Rymer, “Proof That the Steroids-Era Power Surge in Baseball Has Been Stopped,” Bleacher Report, May 22, 2013

Brian M. Mills, “Expert Workers, Performance Standards, and On-the-Job Training: Evaluating Major League Baseball Umpires,” Journal of Economic Literature, August 27, 2014

Jon Roegele, “Baseball’s Strike Zone Expansion Is Out of Control,” Slate, October 15, 2014