As Eric Walker — the real inventor of “moneyball” — puts it, “moneyball is about seeking undervalued commodities.” Perhaps baseball teams have done a better job of acquiring undervalued commodities since the publication of Michael Lewis’s Moneyball in 2003. But arbitrage opportunities are fleeting, as the price of a “bargain” is driven up and it is no longer a “bargain.” Moreover, as Walker explains, “moneyball” has been around since the 1980s and the concept surely had some influence on player selection even before Lewis made it famous.

At any rate, I have analyzed the performance and payrolls of American League (AL) teams for 1988-2011 to determine their effects on teams’ won-lost (W-L) records. I focused on the AL because an analysis of both major leagues would have been complicated by the presence of the designated hitter in the AL and the absence of the DL in the National League. I began with 1988 because that is the first year covered by the USATODAY Salaries Database for baseball. Performance data are from Retrosheet.

What did I learn from those 24 years’ worth of data? This:

1. Payroll does not drive W-L record.

2. Payroll is mainly determined by 7 aspects of performance.

3. W-L record is mainly determined by 9-11 aspects of performance, only 2-4 of which overlap with the determinants of payroll.

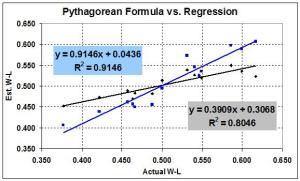

4. W-L record is strongly correlated with the ratio of runs scored (RS) to runs allowed (RA), with an r-squared of 0.89. There is considerable overlap between the determinants of RS-RA and the determinants of W-L record. There is not much overlap between the determinants of RS:RA and the determinants of payroll.

I begin with the relationship between payroll and W-L record:

Payroll index is the ratio of a team’s payroll in a given season to the average payroll of all AL teams in the same season. A regression on W-L record with payroll index as an explanatory variable cannot include additional explanatory variables that are statistically significant (less than 1 percent chance of a random relationship with the dependent variable). As discussed below, this result indicates that payroll index is a proxy for measures of performance that are statistically significant determinants of a W-L record and RS:RA.

The following table summarizes the results of six regressions. Instead of showing the coefficients for the explanatory variables, I have converted them to elasticities, expressed as the percentage increase in a dependent variable that results from a 1-percent increase in the value of the explanatory variable.

Before I walk through the table, I should observe that the figures represent average tendencies over a 24-year span. The figures are significant, but they do not necessarily indicate the best course of action for a given team in a given situation. The best course of action for a given team in a given situation will depend on the team’s options (e.g., players available on the free-agent market), on the likely payoff of those options (e.g., addition to runs scored if player A is signed and player B is traded away), and on the cost of obtaining each payoff (e.g., net addition to payroll if player A is signed and player B is traded).

The results in the payroll index column show that the payrolls of AL teams in 1988-2011 were driven mainly by batters’ on-base percentage (OBP); pitchers’ avoidance of giving up home runs; pitchers’ ability to strike out batters (SO); fielders’ avoidance of errors (ERR); batters’ home runs (HR); catchers’ throwing out base stealers (CS); and batters’ not hitting a lot of triples (3B) — perhaps because of the typical characteristics of triples hitters (e.g., they are not usually home-run hitters).

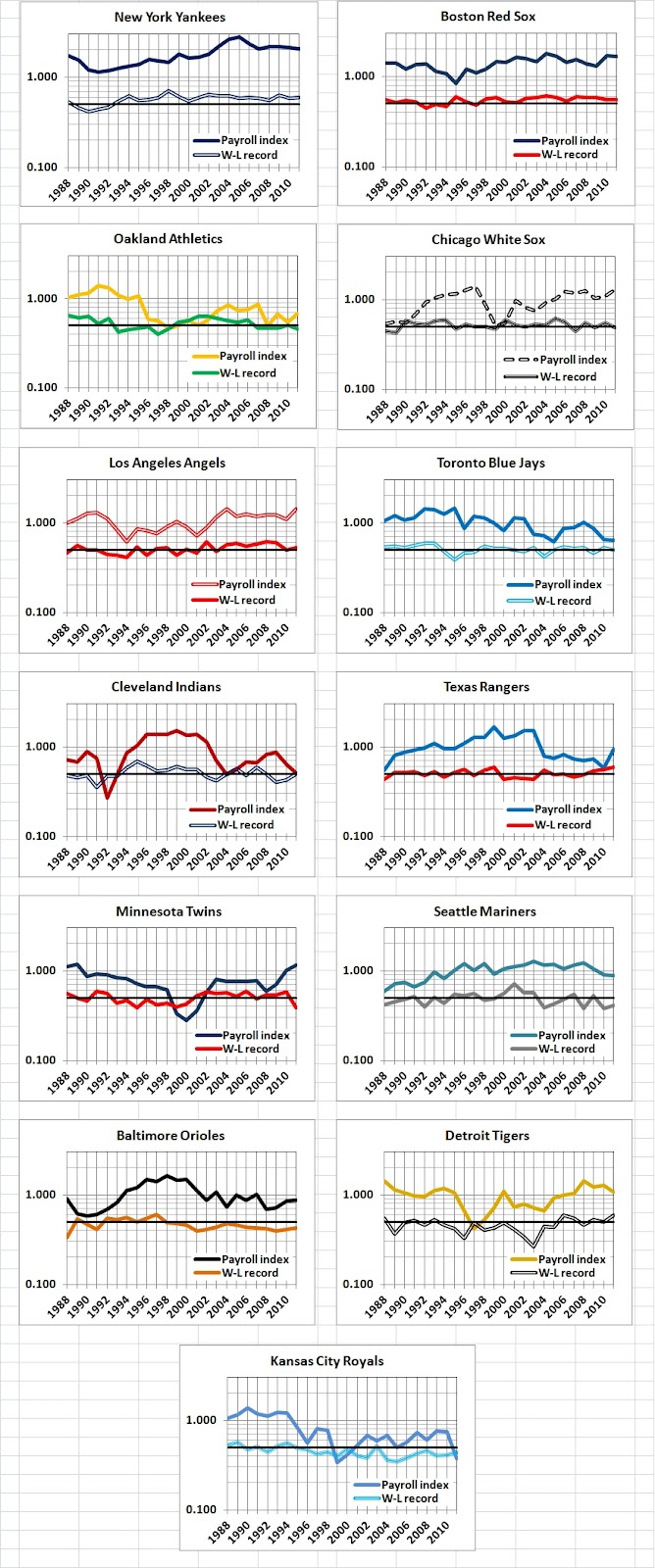

In the next column we see, again, that payroll spending — in the aggregate over 24 seasons — does not strongly influence W-L record. But because payroll is a proxy for several performance variables, no other variable show up as statistically significant when payroll index is used as an explanatory variable. It is important to note, however, that the relatively weak relationship between W-L record and payroll index for the entire AL masks considerable variation across teams. Here is a summary comparison, for the 13 teams that were in the AL in every year from 1988 through 2011:

The Oakland A’s of “moneyball” fame did will for the amount of money spent on payroll, as measured by W-L record divided by payroll index (right-hand column). But, on that measure, the A’s did no better than the Twins, and not a lot better than the Royals and White Sox.

The Yankees were the best team in the AL during 1988-2011, and they paid what it took to be the best. The Red Sox were the second-best team, and they paid accordingly. After that, results were mixed. The A’s paid a lot less than the Yankees and Red Sox, and still won a lot — but did not get much in return when they spent more (correlation coefficient of 0.19, as against 0.50 for the Yankees and 0.31 for the Red Sox). Though an above-average payroll index was not required for a winning record, four of the top six team in W-L and every team with a payroll index of 1.00 or grater had a winning record. All teams but one — the Rangers — managed to eke out some additional wins by increasing their payrolls.

The following graphs illustrate several story lines, such as success with young, low-priced players who then become higher-priced and less-productive players; overspending on once-outstanding veterans whose best seasons were behind them; overspending on promising players whose performance did not rise with their salaries. For ease of reading each team’s W-L record, I have inserted in each graph a horizontal black line at the break-even mark (.500).

Seen in the context of 13 team histories, the A’s look like a team that did well for a while with relatively high-priced players; pared its payroll as its fortunes faded; happened to do well for a while on low-priced players, and then faded as its payroll rose.

Let us now to the column headed W-L record (II) in the first table above. This is where the bat meets the ball, so to speak, because it tells us something about the aspects of performance that determine a team’s W-L record. Except for on-base percentage (OBP), the determinants of payroll have little to do with winning. Defense (represented in fielding average) is far and away the most important determinant of winning. (The payoff of defense may be somewhat overstated, as I will come to.) After that, preventing hits (H) and getting them weigh heavily. Pitchers who save games (SV) are important to winning, as are pitchers who do not give up a lot of walks (BB). Home runs (HR) are just as important as payroll, even though they are down the list of factors that determine payroll.

As mentioned earlier, W-L record is strongly correlated with the ratio of runs scored to runs allowed (RS:RA). The next two columns of the table assess the relationships between RS and various measures of performance; the right-hand column deals with RA. On the offensive side, HR remains important, as does OBP appear, directly and in the form of key elements — H, BA, and BB. On the defense side, fielding is key (more below). Next are H, BB, and HR allowed by pitchers, meaning that allowing relatively few H, BB, and HR are keys to the defensive side of the game. Another key, though a less important one, is striking out batters (SO).

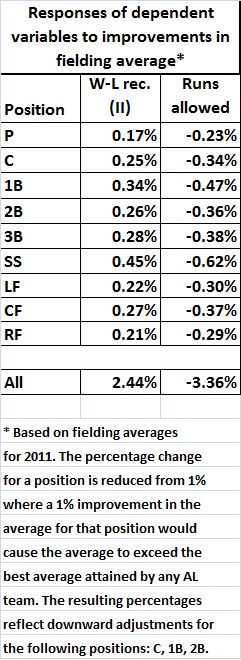

As for fielding, a position-by-position view is more relevant, and the possibility of obtaining better fielding is overstated for some positions. The following table affords the position-by-position view and eliminates the overstatements:

What this tells us is that improved fielding, at any position, can strongly improve a team’s chances of winning, even though fielding is not among the key determinants of payroll.