You can’t go back home to your family, back home to your childhood … back home to a young man’s dreams of glory and of fame … back home to places in the country, back home to the old forms and systems of things which once seemed everlasting but which are changing all the time – back home to the escapes of Time and Memory.

— Thomas Wolfe, You Can’t Go Home Again

* * *

I have just begun to read a re-issue of Making It, Norman Podhoretz‘s memoir that stirred up the literati of New York City. According to Jennifer Schuessler (“Norman Podhoretz: Making Enemies,” Publisher’s Weekly, January 25, 1999), Podhoretz’s

frank 1967 account of the lust for success that propelled him from an impoverished childhood in Brooklyn to the salons of Manhattan, … scandalized the literary establishment that once hailed him as something of a golden boy. His agent wouldn’t represent it. His publisher refused to publish it. And just about everybody hated it. In 1972, Podhoretz’s first high-profile personal squabble, with Random House’s Jason Epstein, went public when the New York Times Magazine published an article called “Why Norman and Jason Aren’t Talking.” By 1979, when Podhoretz published Breaking Ranks, a memoir of his conversion from radicalism to militant conservatism, it seemed just about everybody wasn’t talking to Norman.

Next month, Podhoretz will add another chapter to his personal war chronicle with the publication of Ex-Friends: Falling Out with Allen Ginsberg, Lionel and Diana Trilling, Lillian Hellman, Hannah Arendt, and Norman Mailer. In this short, sharp, unabashedly name-dropping book, Podhoretz revisits the old battles over communism and the counterculture, not to mention his bad reviews. But for all his talk of continued struggle against the “regnant leftist culture that pollutes the spiritual and cultural air we all breathe,” the book is a frankly nostalgic, even affectionate look back at the lost world of “the Family,” the endlessly quarreling but close-knit group of left-leaning intellectuals that gathered in the 1940s and ’50s around such magazines as the Partisan Review and Commentary.

Given this bit of background, you shouldn’t be surprised that it was Podhoretz who said that a conservative is a liberal who has been mugged by reality. Nor should you be surprised that Podhoretz wrote this about Barack Obama (which I quote in “Presidential Treason“):

His foreign policy, far from a dismal failure, is a brilliant success as measured by what he intended all along to accomplish….

… As a left-wing radical, Mr. Obama believed that the United States had almost always been a retrograde and destructive force in world affairs. Accordingly, the fundamental transformation he wished to achieve here was to reduce the country’s power and influence. And just as he had to fend off the still-toxic socialist label at home, so he had to take care not to be stuck with the equally toxic “isolationist” label abroad.

This he did by camouflaging his retreats from the responsibilities bred by foreign entanglements as a new form of “engagement.” At the same time, he relied on the war-weariness of the American people and the rise of isolationist sentiment (which, to be sure, dared not speak its name) on the left and right to get away with drastic cuts in the defense budget, with exiting entirely from Iraq and Afghanistan, and with “leading from behind” or using drones instead of troops whenever he was politically forced into military action.

The consequent erosion of American power was going very nicely when the unfortunately named Arab Spring presented the president with several juicy opportunities to speed up the process. First in Egypt, his incoherent moves resulted in a complete loss of American influence, and now, thanks to his handling of the Syrian crisis, he is bringing about a greater diminution of American power than he probably envisaged even in his wildest radical dreams.

For this fulfillment of his dearest political wishes, Mr. Obama is evidently willing to pay the price of a sullied reputation. In that sense, he is by his own lights sacrificing himself for what he imagines is the good of the nation of which he is the president, and also to the benefit of the world, of which he loves proclaiming himself a citizen….

No doubt he will either deny that anything has gone wrong, or failing that, he will resort to his favorite tactic of blaming others—Congress or the Republicans or Rush Limbaugh. But what is also almost certain is that he will refuse to change course and do the things that will be necessary to restore U.S. power and influence.

And so we can only pray that the hole he will go on digging will not be too deep for his successor to pull us out, as Ronald Reagan managed to do when he followed a president into the White House whom Mr. Obama so uncannily resembles. [“Obama’s Successful Foreign Failure,” The Wall Street Journal, September 8, 2013]

Though I admire Podhoretz’s willingness to follow reality to its destination in conservatism — because I made the same journey myself — I am drawn to his memoir by another similarity between us. In the Introduction to the re-issue, Terry Teachout writes:

Making It is never more memorable than when it describes its author’s belated discovery of “the brutal bargain” to which he was introduced by “Mrs. K.,” a Brooklyn schoolteacher who took him in hand and showed him that the precocious but rough-edged son of working-class Jews from Galicia could aspire to greater things— so long as he turned his back on the ghettoized life of his émigré parents and donned the genteel manners of her own class. Not until much later did he realize that the bargain she offered him went even deeper than that:

She was saying that because I was a talented boy, a better class of people stood ready to admit me into their ranks. But only on one condition: I had to signify by my general deportment that I acknowledged them as superior to the class of people among whom I happened to have been born. . . . what I did not understand, not in the least then and not for a long time afterward, was that in matters having to do with “art” and “culture” (the “life of the mind,” as I learned to call it at Columbia), I was being offered the very same brutal bargain and accepting it with the wildest enthusiasm.

So he did, and he never seriously doubted that he had done the only thing possible by making himself over into an alumnus of Columbia and Cambridge and a member of the educated, art-loving upper middle class. At the same time, though, he never forgot what he had lost by doing so, having acquired in the process “a distaste for the surroundings in which I was bred, and ultimately (God forgive me) even for many of the people I loved.”

It’s not an unfamiliar story. But it’s a story that always brings a pang to my heart because it reminds me too much of my own attitudes and behavior as I “climbed the ladder” from the 1960s to the 1990s. Much as I regret the growing gap between me and my past, I have learned from experience that I can’t go back, and don’t want to go back.

What happened to me is probably what happened to Norman Podhoretz and tens of millions of other Americans. We didn’t abandon our past; we became what was written in our genes.

This mini-memoir is meant to illustrate that thesis. It is aimed at those readers who can’t relate to a prominent New Yorker, but who might see themselves in a native of flyover country.

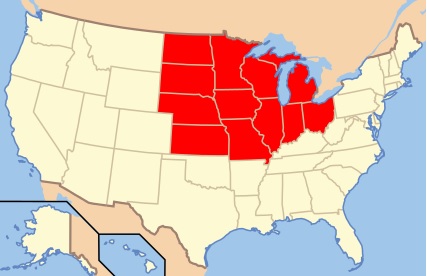

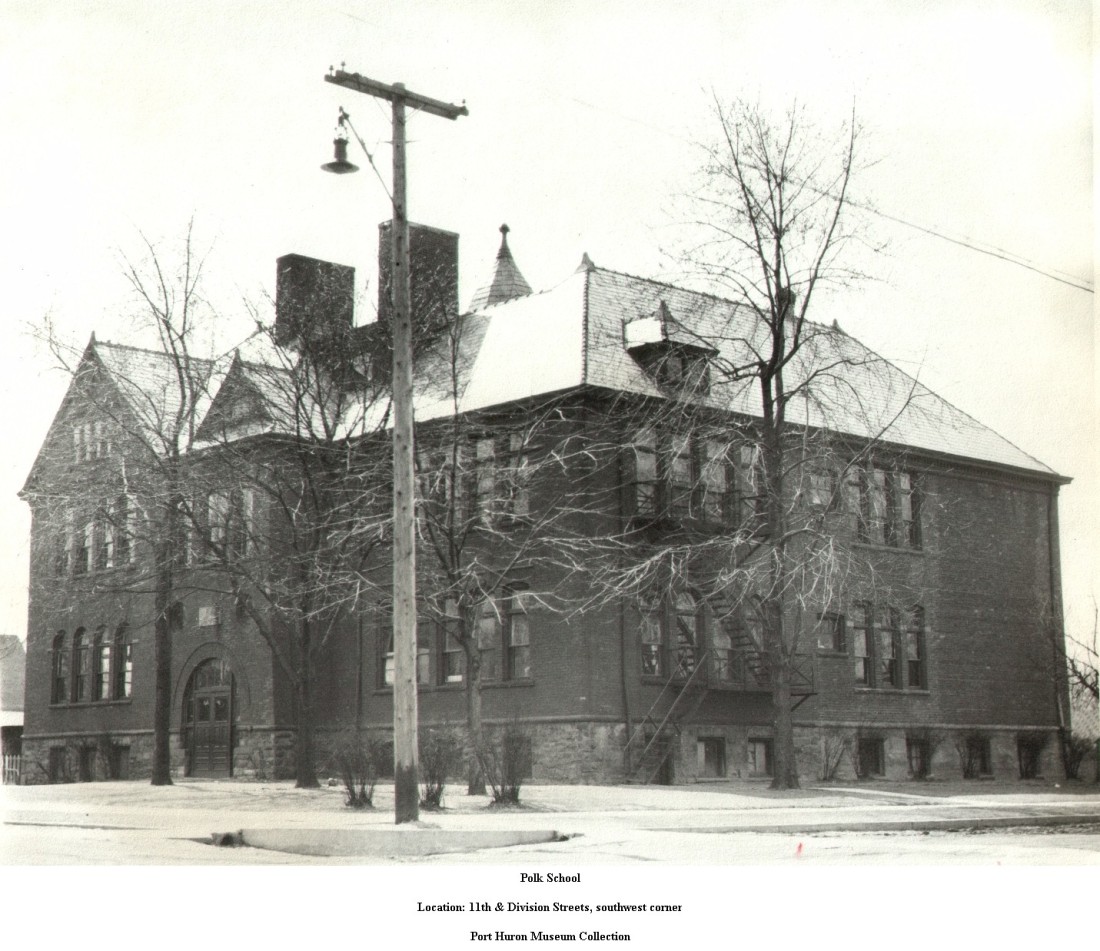

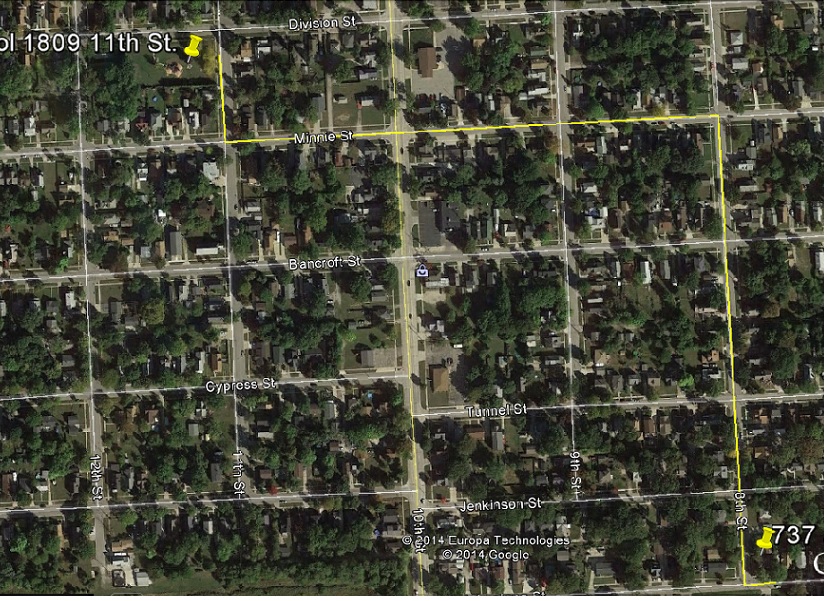

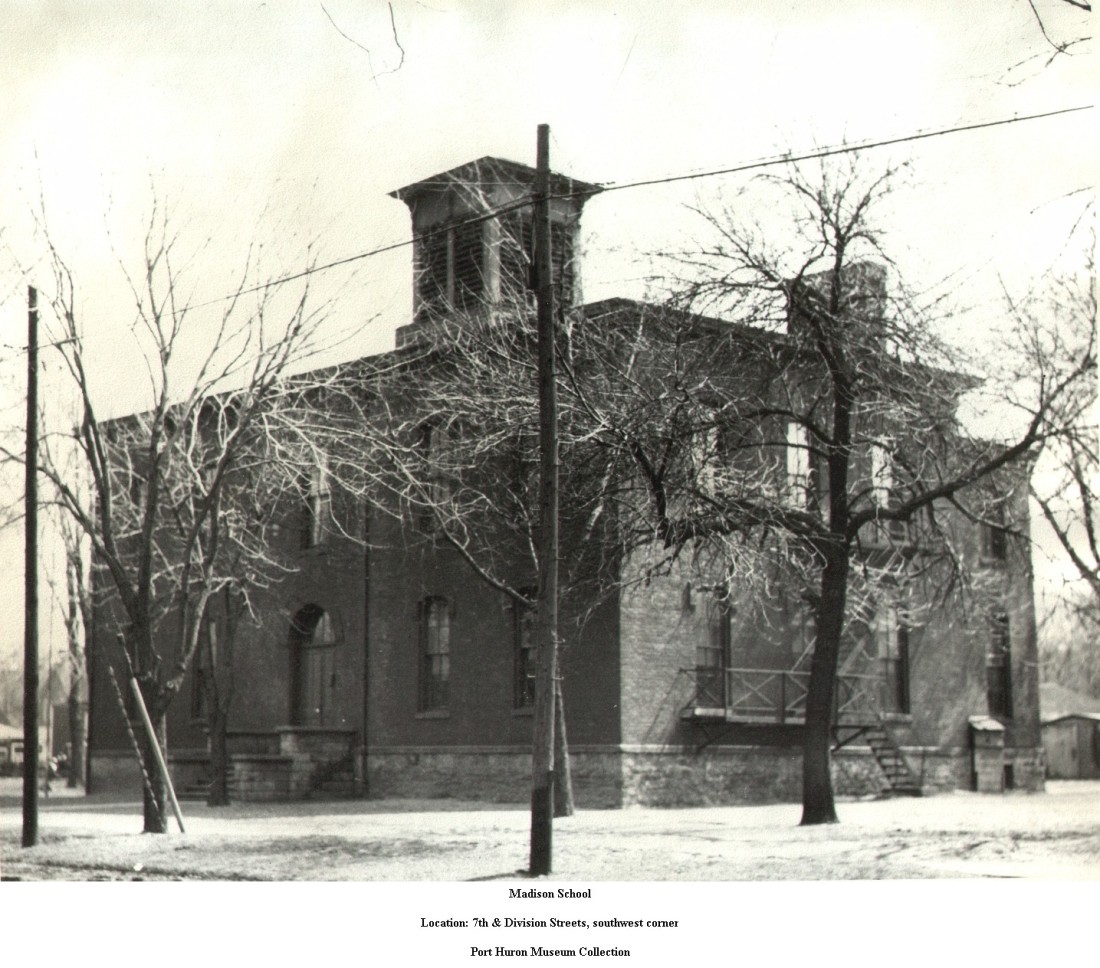

My “ghetto” wasn’t a Jewish enclave like Podhoretz’s Brownsville, but an adjacent pair of small cities in the eastern flatlands of Michigan, both of them predominantly white and working-class. They are not suburbs of Detroit — as we used to say emphatically — nor of any other largish city. We were geographically and culturally isolated from the worst and best that “real” cities have to offer in the way of food, entertainment, and ethnic variety.

My parents’ roots, and thus my cultural inheritance, were in small cities, towns and villages in Michigan and Ontario. Life for my parents, as for their forbears, revolved around making a living, “getting ahead” by owning progressively nicer (but never luxurious) homes and cars, socializing with friends over card games, and keeping their houses and yards neat and clean.

All quite unexceptional, or so it seemed to me as I was growing up. It only began to seem exceptional when I became the first scion of the the family tree to “go away to college,” as we used to say. (“Going away” as opposed to attending a local junior college, as did my father’s younger half-brother about eight years before I matriculated.)

Soon after my arrival on the campus of a large university, whose faculty and students hailed from around the world, I began to grasp the banality of my upbringing in comparison to the cultural richness and sordid reality of the wider world. It was a richness and reality of which my home-town contemporaries and I knew little because we were raised in the days of Ozzie and Harriet — before the Beatles, Woodstock, bearded men with pony-tails, shacking up as a social norm, widespread drug use, and the vivid depiction of sex in all of its natural and unnatural variety.

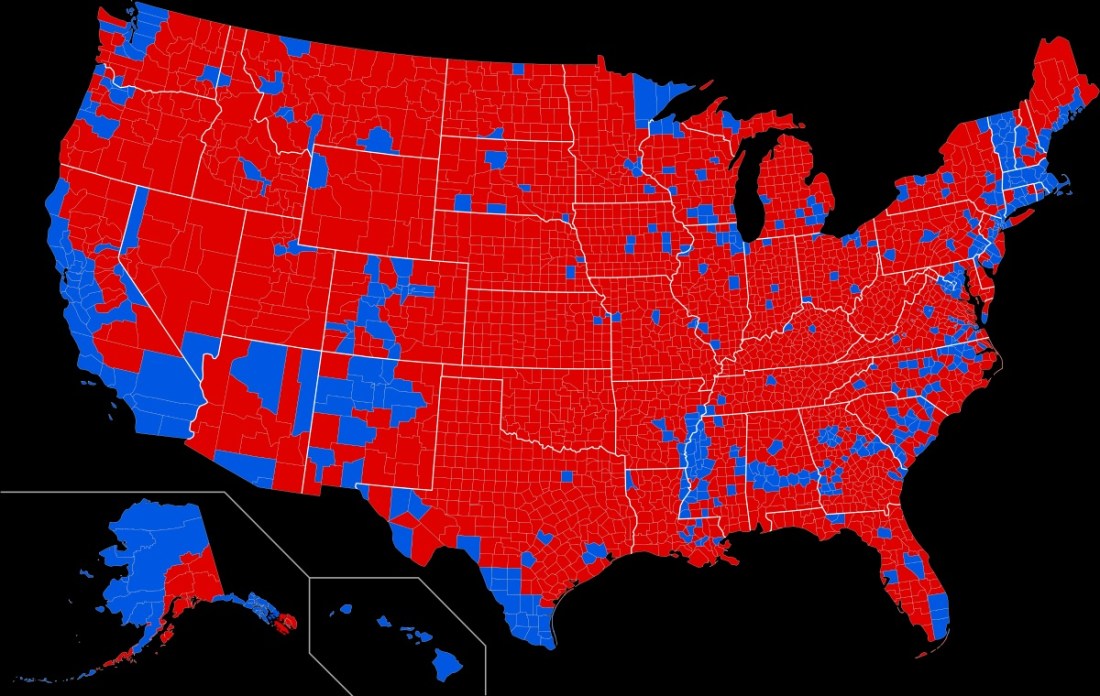

My upbringing, like that of my home-town contemporaries was almost apolitical. If we overheard our parents talking about politics, we overheard a combination of views that today seems unlikely: suspicion of government; skepticism about unions (my father had to join one in order to work), disdain for “fat cats”; sympathy for “the little guy”; and staunch patriotism. There was nothing about civil rights and state-enforced segregation, which were seen (mistakenly) as peculiarly Southern issues. Their own racism was seldom in evidence because blacks generally “knew their place” in our white-dominated communities.

And then, as a student at a cosmopolitan Midwestern university (that isn’t an oxymoron), I began to learn — in and out of class. The out-of-class lessons came through conversations with students whose backgrounds differed greatly from mine, including two who had been displaced persons in the wake of World War II. My first-year roommate was a mild-mannered Iranian doctoral student whose friends (some of them less mild-mannered) spoke openly about the fear in which Iranians lived because of SAVAK‘s oppressive practices. In my final year as an undergraduate I befriended some married graduate students, one of whom (an American) had spent several years in Libya as a geologist for an American oil company and had returned to the States with an Italian wife.

One of the off-campus theaters specialized in foreign films, which I had never before seen, and which exposed me to people, places, attitudes, and ideas that were intellectually foreign to me, but which I viewed avidly and with acceptance. My musical education was advanced by a friendship with a music major, through whom I met other music majors and learned much about classical music and, of all things, Gilbert and Sullivan. One of the music majors was a tenor who had to learn The Mikado, and did so by playing a recording of it over and over. I became hooked, and to this day can recite large chunks of the libretto. I used to sing them, but my singing days are over.

Through my classes — and often through unassigned reading — I learned how to speak and read French (fluently, those many years ago), and ingested various-sized doses of philosophy, history (ancient and modern), sociology, accounting (the third of four majors), and several other things that escape me at the moment.

Through economics (my fourth and final major), I learned (but didn’t then question), the contradictory tenets of microeconomics (how markets work to allocate resources and satisfy wants efficiently) and macroeconomics (then dominated by the idea of government’s indispensable role in the economic order). But I was drawn in by the elegance of economic theory, and mistook its spurious precision for deep understanding. Though I have since rejected macroeconomic orthodoxy (e.g., see this).

My collegiate “enlightenment” was mild, by today’s standards, but revelatory to a small-city boy. And I was among the still relatively small fraction of high-school graduates who went away to college. So my exposure to a variety of people, cultures, and ideas immediately set me apart — apart not only from my parents and the members of their generation, but also apart from most of the members of my own generation.

What set me apart more than anything was my loss of faith. In my second year I went from ostentatiously devout Catholicism to steadfast agnosticism in a span of weeks. I can’t reconstruct the transition at a remove of almost 60 years, but I suspect that it involved a mixture of delayed adolescent rebellion, a reckoning (based on things I had learned) that the roots of religion lay in superstition, and a genetic predisposition toward skepticism (my father was raised Protestant but scorned religion in his mild way). At any rate, when I walked out of church in the middle of Mass one Sunday morning, I felt as if I had relieved myself of a heavy burden and freed my mind for the pursuit of knowledge.

The odd thing is that, to this day, I retain feelings of loyalty to the Church of my youth — the Church of the Latin Mass (weekly on Sunday morning, not afternoon or evening), strict abstinence from meat on Friday, confession on Saturday, fasting from midnight on Sunday (if one were in a state of grace and fit for Holy Communion), and the sharp-tongued sisters with sharp-edged rulers who taught Catechism on Saturday mornings (parochial school wasn’t in my parents’ budget). I have therefore been appalled, successively, by Vatican Council II, most of the popes of the past 50 years, the various ways in which being a Catholic has become easier, and (especially) the egregious left-wing babbling of Francis. And yet I remain an agnostic who only in recent years has acknowledged the logical necessity of a Creator, but probably not the kind of Creator who is at the center of formal religion. Atheism — especially of the strident variety — is merely religion turned upside down; a belief in something that is beyond proof; I scorn it.

To complete this aside, I must address the canard peddled by strident atheists and left-wingers (there’s a lot of overlap) about the evil done in the name of religion, I say this: Religion doesn’t make fanatics, it attracts them (in relatively small numbers), though some Islamic sects seem to be bent on attracting and cultivating fanaticism. Far more fanatical and attractive to fanatics are the “religions” of communism, socialism (including Hitler’s version), and progressivism (witness the snowflakes and oppressors who now dominate the academy). I doubt that the number of murders committed in the name of religion amounts to one-tenth of the number of murders committed by three notable anti-religionists: Hitler (yes, Hitler), Stalin, and Mao. I also believe — with empirical justification — that religion is a bulwark of liberty; whereas, the cult of libertarianism — usually practiced by agnostics and atheists — is not (e.g., this post and the others linked to therein).

It’s time to return to the chronological thread of my narrative. I have outlined my graduate-school and work experiences in “About.” The main thing to note here is what I learned during the early mid-life crisis which took me away from the D.C. rat race for about three years, as owner-operator of a (very) small publishing company in a rural part of New York State.

In sum, I learned to work hard. Before my business venture I had coasted along using my intelligence but not a lot of energy, but nevertheless earning praise and good raises. I was seldom engaged it what I was doing: the work seemed superficial and unconnected to anything real to me. That changed when I became a business owner. I had to meet a weekly deadline or lose advertisers (and my source of income), master several new skills involved in publishing a weekly “throwaway” (as the free Pennysaver was sometimes called), and work six days a week with only two brief respites in three years. Something clicked, and when I gave up the publishing business and returned to the D.C. area, I kept on working hard — as if my livelihood depended on it.

And it did. Much as I had loved being my own boss, I wanted to live and retire more comfortably than I could on the meager income that flowed uncertainly from the Pennysaver. Incentives matter. So in the 18 years after my return to the D.C. area I not only kept working hard and with fierce concentration, but I developed (or discovered) a ruthless streak that propelled me into the upper echelon of the think-tank.

And in my three years away from the D.C. area I also learned, for the first time, that I couldn’t go home again.

I was attracted to the publishing business because of its location in a somewhat picturesque village. The village was large enough to sport a movie theater, two super markets, and a variety of commercial establishments, including restaurants, shoe stores, clothing stores, jewelers, a Rite-Aid drug store, and even a J.J. Newberry dime store. It also had many large, well-kept homes All in all, it appealed to me because, replete with a “real” main street, it reminded me of the first small city in which I grew up.

But after working and associating with highly educated professionals, and after experiencing the vast variety of restaurants, museums, parks, and entertainment of the D.C. area, I found the village and its natives dull. Not only dull, but also distant. They were humorless and closed to outsiders. It came to me that the small cities in which I had grown up were the same way. My memories of them were distorted because they were memories of a pre-college boy who had yet to experience life in the big city. They were memories of a boy whose life centered on his parents and a beloved grandmother (who lived in a small village of similarly golden memory).

You can’t go home again, metaphorically, if you’ve gone away and lived a different life. You can’t because you are a different person than you were when you were growing up. This lesson was reinforced at the 30-year reunion of my high-school graduating class, which occurred several years after my business venture and a few years after I had risen into the upper echelon of the think-tank.

There I was, with my wife and sister (who graduated from the same high school eight years after I did), happily anticipating an evening of laughter and shared memories. We were seated at a table with two fellows who had been good friends of mine (and their wives, whom I didn’t know). It was deadly boring; the silences yawned; we had nothing to say to each other. One of the old friends, who had been on the wagon, was so unnerved by the forced bonhomie of the occasion that he fell off the wagon. Attempts at mingling after dinner were awkward. My wife and sister readily agreed to abandon the event. We drove several miles to an elegant, river-front hotel where we had a few drinks on the deck. Thus the evening ended on a cheery note, despite the cool, damp drizzle. (A not untypical August evening in Michigan.)

I continued to return to Michigan for another 27 years, making what might be my final trip for the funeral of my mother, who lived to the age of 99. But I went just to see my parents and siblings, and then only out of duty.

The golden memories of my youth remain with me, but I long ago gave up the idea of reliving the past that is interred in those memories.