Part One gives excerpts of W.Somerset Maugham’s candid insights about the craft of writing. Part Two gives my advice to writers of non-fiction works. Part Three recommends some writings about writing, some writers to emulate, and a short list of reference works. This part delivers some sermons about practices to follow if you wish to communicate effectively, be taken seriously, and not be thought of as a semi-literate, self-indulgent, faddish dilettante. (In Part Three, I promised sermonettes, but they grew into sermons as I wrote.)

The first section, “Stasis, Progress, Regress, and Language,” comes around to a defense of prescriptivism in language. The second section, “Illegitimi Non Carborundum Lingo” (mock-Latin for “Don’t Let the Bastards Wear Down the Language”), counsels steadfastness in the face of political correctness and various sloppy usages.

STASIS, PROGRESS, REGRESS, AND LANGUAGE

To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven….

Ecclesiastes 3:1 (King James Bible)

Nothing man-made is permanent; consider, for example, the list of empires here. In spite of the history of empires — and other institutions and artifacts of human endeavor — most people seem to believe that the future will be much like the present. And if the present embodies progress of some kind, most people seem to expect that progress to continue.

Things do not simply go on as they have been without the expenditure of requisite effort. Take the Constitution’s broken promises of liberty, about which I have written so much. Take the resurgence of Russia as a rival for international influence. This has been in the works for about 20 years, but didn’t register on most Americans until the recent Crimean crisis and related events in Ukraine. What did Americans expect? That the U.S. could remain the unchallenged superpower while reducing its armed forces to the point that they were strained by relatively small wars in Afghanistan and Iraq? That Vladimir Putin would be cowed by an American president who had so blatantly advertised his hopey-changey attitude toward Iran and Islam, while snubbing traditional allies like Poland and Israel?

Turning to naïveté about progress, I offer Steven Pinker’s fatuous The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined. Pinker tries to show that human beings are becoming kinder and gentler. I have much to say in another post about Pinker’s thesis. One of my sources is Robert Epstein’s review of Pinker’s book. This passage is especially apt:

The biggest problem with the book … is its overreliance on history, which, like the light on a caboose, shows us only where we are not going. We live in a time when all the rules are being rewritten blindingly fast—when, for example, an increasingly smaller number of people can do increasingly greater damage. Yes, when you move from the Stone Age to modern times, some violence is left behind, but what happens when you put weapons of mass destruction into the hands of modern people who in many ways are still living primitively? What happens when the unprecedented occurs—when a country such as Iran, where women are still waiting for even the slightest glimpse of those better angels, obtains nuclear weapons? Pinker doesn’t say.

Less important in the grand scheme, but no less wrong-headed, is the idea of limitless progress in the arts. To quote myself:

In the early decades of the twentieth century, the visual, auditory, and verbal arts became an “inside game.” Painters, sculptors, composers (of “serious” music), choreographers, and writers of fiction began to create works not for the enjoyment of audiences but for the sake of exploring “new” forms. Given that the various arts had been perfected by the early 1900s, the only way to explore “new” forms was to regress toward primitive ones — toward a lack of structure…. Aside from its baneful influence on many true artists, the regression toward the primitive has enabled persons of inferior talent (and none) to call themselves “artists.” Thus modernism is banal when it is not ugly.

Painters, sculptors, etc., have been encouraged in their efforts to explore “new” forms by critics, by advocates of change and rebellion for its own sake (e.g., “liberals” and “bohemians”), and by undiscriminating patrons, anxious to be au courant. Critics have a special stake in modernism because they are needed to “explain” its incomprehensibility and ugliness to the unwashed.

The unwashed have nevertheless rebelled against modernism, and so its practitioners and defenders have responded with condescension, one form of which is the challenge to be “open minded” (i.e., to tolerate the second-rate and nonsensical). A good example of condescension is heard on Composers Datebook, a syndicated feature that runs on some NPR stations. Every Composers Datebook program closes by “reminding you that all music was once new.” As if to lump Arnold Schoenberg and John Cage with Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven.

All music, painting, sculpture, dance, and literature was once new, but not all of it is good. Much (most?) of what has been produced since 1900 is inferior, self-indulgent crap.

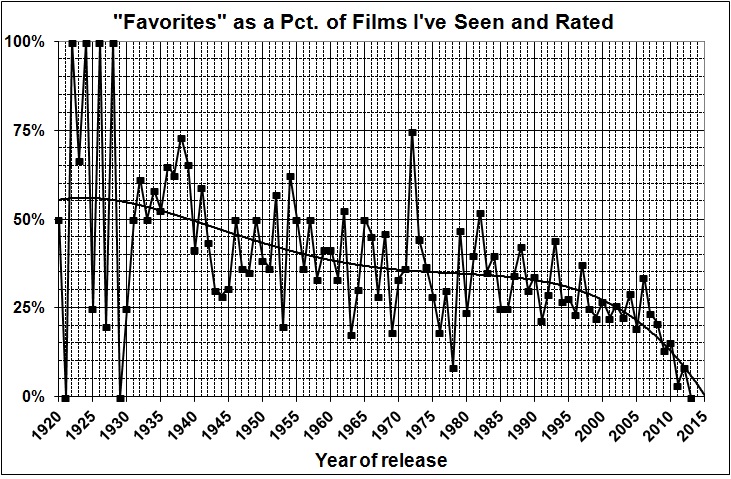

And most of the ticket-buying public knows it. Take opera, for example. A recent article purports to show that “Opera is dead, in one chart” (Christopher Ingraham, The Washington Post, October 31, 2014). Here’s the chart and the writer’s interpretation of it:

The chart shows that opera ceased to exist as a contemporary art form roughly around 1970. It’s from a blog post by composer and programmer Suby Raman, who scraped the Met’s public database oF performances going back to the 19th century. As Raman notes, 50 years is an insanely low bar for measuring the “contemporary” – in pop music terms, it would be like considering The Beatles’ I Wanna Hold Your Hand as cutting-edge.

Back at the beginning of the 20th century, anywhere from 60 to 80 percent of Met performances were of operas composed in some time in the 50 years prior. But since 1980, the share of contemporary performances has surpassed 10 percent only once.

Opera, as a genre, is essentially frozen in amber – Raman found that the median year of composition of pieces performed at the Met has always been right around 1870. In other words, the Met is essentially performing the exact same pieces now that it was 100 years ago….

Contrary to Ingraham, opera isn’t dead; for example, there are more than 220 active opera companies in the U.S. It’s just that there’s little demand for operatic works written after the late 1800s. Why? Because most opera-lovers don’t want to hear the strident, discordant, unmelodic trash that came later. Giacomo Puccini, who wrote melodic crowd-pleasers until his death in 1924, is an exception that proves the rule.

It occurred to me recently that language is in the same parlous state as the arts. Written and spoken English improved steadily as Americans became more educated — and as long as that education included courses which prescribed rules of grammar and usage. By “improved” I mean that communication became easier and more effective; specifically:

- A larger fraction of Americans followed the same rules in formal communications (e.g., speeches, business documents, newspapers, magazines, and books,).

- Movies and radio and TV shows also tended to follow those rules, thereby reaching vast numbers of Americans who did little or no serious reading.

- There was a “trickle down” effect on Americans’ written and spoken discourse, especially where it involved mere acquaintances or strangers. Standard American English became a kind of lingua franca, which enabled the speaker or writer to be understood and taken seriously.

I call that progress.

There is, however, an (unfortunately) influential attitude toward language known as descriptivism. It is distinct from (and often opposed to) rule-setting (prescriptivism). Consider this passage from the first chapter of an online text:

Prescriptive grammar is based on the idea that there is a single right way to do things. When there is more than one way of saying something, prescriptive grammar is generally concerned with declaring one (and only one) of the variants to be correct. The favored variant is usually justified as being better (whether more logical, more euphonious, or more desirable on some other grounds) than the deprecated variant. In the same situation of linguistic variability, descriptive grammar is content simply to document the variants – without passing judgment on them.

This misrepresents the role of prescriptive grammar. It’s widely understood that there’s more than one way of saying something, and more than one way that’s understandable to others. The rules of prescriptive grammar, when followed, improve understanding, in two ways. First, by avoiding utterances that would be incomprehensible or, at least, very hard to understand. Second, by ensuring that utterances aren’t simply ignored or rejected out of hand because their form indicates that the writer or speaker is either ill-educated or stupid.

What, then, is the role of descriptive grammar? The authors offer this:

[R]ules of descriptive grammar have the status of scientific observations, and they are intended as insightful generalizations about the way that speakers use language in fact, rather than about the way that they ought to use it. Descriptive rules are more general and more fundamental than prescriptive rules in the sense that all sentences of a language are formed in accordance with them, not just a more or less arbitrary subset of shibboleth sentences. A useful way to think about the descriptive rules of a language … is that they produce, or generate, all the sentences of a language. The prescriptive rules can then be thought of as filtering out some (relatively minute) portion of the entire output of the descriptive rules as socially unacceptable.

Let’s consider the assertion that descriptive rules produce all the sentences of a language. What does that mean? It seems to mean the actual rules of a language can be inferred by examining sentences uttered or written by users of the language. But which users? Native users? Adults? Adults who have graduated from high-school? Users with IQs of at least 85?

Pushing on, let’s take a closer look at descriptive rules and their utility. The authors say that

we adopt a resolutely descriptive perspective concerning language. In particular, when linguists say that a sentence is grammatical, we don’t mean that it is correct from a prescriptive point of view, but rather that it conforms to descriptive rules….

The descriptive rules amount to this: They conform to practices that a speakers and writers actually use in an attempt to convey ideas, whether or not the practices state the ideas clearly and concisely. Thus the authors approve of these sentences because they’re of a type that might well occur in colloquial speech:

Over there is the guy who I went to the party with.

Over there is the guy with whom I went to the party.

(Both are clumsy ways of saying “I went to the party with that person.”)

Bill and me went to the store.

(“Bill and I went to the store.” or “Bill went to the store with me.” or “I went to the store with Bill.” Aha! Three ways to say it correctly, not just one way.)

But the authors label the following sentences as ungrammatical because they don’t comport with the colloquial speech:

Over there is guy the who I went to party the with.

Over there is the who I went to the party with guy.

Bill and me the store to went.

In other words, the authors accept as grammatical anything that a speaker or writer is likely to say, according to the “rules” that can be inferred from colloquial speech and writing. It follows that whatever is is right, even “Bill and me to the store went” or “Went to the store Bill and me,” which aren’t far-fetched variations on “Bill and me went to the store.” (Yoda-isms they read like.) They’re understandable, but only with effort. And further evolution would obliterate their meaning.

The fact is that the authors of the online text — like descriptivists generally — don’t follow their own anarchistic prescription. Wilson Follett puts it this way in Modern American Usage: A Guide:

It is … one of the striking features of the libertarian position [with respect to language] that it preaches an unbuttoned grammar in a prose style that is fashioned with the utmost grammatical rigor. H.L. Mencken’s two thousand pages on the vagaries of the American language are written in the fastidious syntax of a precisian. If we go by what these men do instead of by what they say, we conclude that they all believe in conventional grammar, practice it against their own preaching, and continue to cultivate the elegance they despise in theory….

[T]he artist and the user of language for practical ends share an obligation to preserve against confusion and dissipation the powers that over the centuries the mother tongue has acquired. It is a duty to maintain the continuity of speech that makes the thought of our ancestors easily understood, to conquer Babel every day against the illiterate and the heedless, and to resist the pernicious and lulling dogma that in language … whatever is is right and doing nothing is for the best (pp. 30-1).

Follett also states the true purpose of prescriptivism, which isn’t to prescribe rules for their own sake:

[This book] accept[s] the long-established conventions of prescriptive grammar … on the theory that freedom from confusion is more desirable than freedom from rule…. (op. cit., p. 243).

E.B. White puts it more colorfully in his introduction to The Elements of Style. Writing about William Strunk Jr., author of the original version of the book, White says:

All through The Elements of Style one finds evidence of the author’s deep sympathy for the reader. Will felt that the reader was in serious trouble most of the time, a man floundering in a swamp, and that it was the duty of anyone attempting to write English to drain this swamp quickly and get his man up on dry ground, or at least throw him a rope. In revising the text, I have tried to hold steadily in mind this belief of his, this concern for the bewildered reader (p. xvi, Third Edition).

Descriptivists would let readers founder in the swamp of incomprehensibility. If descriptivists had their way — or what they claim to be their way — American English would, like the arts, recede into formless primitivism.

Eternal vigilance about language is the price of comprehensibility.

ILLEGITIMI NON CARBORUNDUM LINGO

The vigilant are sorely tried these days. What follows are several restrained rants about some practices that should be resisted and repudiated.

Eliminate Filler Words

When I was a child, most parents and all teachers promptly ordered children to desist from saying “uh” between words. “Uh” was then the filler word favored by children, adolescents, and even adults. The resort to “uh” meant that the speaker was stalling because he had opened his mouth without having given enough thought to what he meant to say.

Next came “you know.” It has been displaced, in the main, by “like,” where it hasn’t been joined to “like” in the formation “like, you know.”

The need of a filler word (or phrase) seems ineradicable. Too many people insist on opening their mouths before thinking about what they’re about to say. Given that, I urge Americans in need of a filler word to use “uh” and eschew “like” and “like, you know.” “Uh” is far less distracting and irritating than the rat-a-tat of “like-like-like-like.”

Of course, it may be impossible to return to “uh.” Its brevity may not give the users of “like” enough time to organize their TV-smart-phone-video-game-addled brains and deliver coherent speech.

In any event, speech influences writing. Sloppy speech begets sloppy writing, as I know too well. I have spent the past 50 years of my life trying to undo habits of speech acquired in my childhood and adolescence — habits that still creep into my writing if I drop my guard.

Don’t Abuse Words

How am I supposed to know what you mean if you abuse perfectly good words? Here I discuss four prominent examples of abuse.

Anniversary

Too many times in recent years I’ve heard or read something like this: “Sally and me are celebrating our one-year anniversary.” The “me” is bad enough; “one-year anniversary” (or any variation of it) is truly egregious.

The word “anniversary” means “the annually recurring date of a past event.” To write or say “x-year anniversary” is redundant as well as graceless. Just write or say “first anniversary,” “two-hundred fiftieth anniversary,” etc., as befits the occasion.

To write or say “x-month anniversary” is nonsensical. Something that happened less than a year ago can’t have an anniversary. What is meant is that such-and-such happened “x” months ago. Just say it.

Data

A person who writes or says “data is” is at best an ignoramus and at worst a Philistine.

Language, above all else, should be used to make one’s thoughts clear to others. The pairing of a plural noun and a singular verb form is distracting, if not confusing. Even though datum is seldom used by Americans, it remains the singular foundation of data, which is the plural form. Data, therefore, never “is”; data always “are.”

H.W. Fowler says:

Latin plurals sometimes become singular English words (e.g., agenda, stamina) and data is often so treated in U.S.; in Britain this is still considered a solecism… (A Dictionary of Modern English Usage, Second Edition, p.119).

But Wilson Follett is better on the subject:

Those who treat data as a singular doubtless think of it as a generic noun, comparable to knowledge or information… [TEA: a generous interpretation]. The rationale of agenda as a singular is its use to mean a collective program of action, rather than separate items to be acted on. But there is as yet no obligation to change the number of data under the influence of error mixed with innovation (op. cit., pp. 130-1).

Hopefully and Its Brethren

Mark Liberman of Language Log discusses

the AP Style Guide’s decision to allow the use of hopefully as a sentence adverb, announced on Twitter at 6:22 a.m. on 17 April 2012:

Hopefully, you will appreciate this style update, announced at #aces2012. We now support the modern usage of hopefully: it’s hoped, we hope.

Liberman, who is a descriptivist, defends AP’s egregious decision. His defense consists mainly of citing noted writers who have used “hopefully” where they meant “it is to be hoped.” I suppose that if those same noted writers had chosen to endanger others by driving on the wrong side of the road, Liberman would praise them for their “enlightened” approach to driving.

Geoff Nunberg also defends “hopefully“ in “The Word ‘Hopefully’ Is Here to Stay, Hopefully,” which appears at npr.org. Numberg (or the headline writer) may be right in saying that “hopefully” is here to stay. But that does not excuse the widespread use of the word in ways that are imprecise and meaningless.

The crux of Nunberg’s defense is that “hopefully” conveys a nuance that “language snobs” (like me) are unable to grasp:

Some critics object that [“hopefully” is] a free-floating modifier (a Flying Dutchman adverb, James Kirkpatrick called it) that isn’t attached to the verb of the sentence but rather describes the speaker’s attitude. But floating modifiers are mother’s milk to English grammar — nobody objects to using “sadly,” “mercifully,” “thankfully” or “frankly” in exactly the same way.

Or people complain that “hopefully” doesn’t specifically indicate who’s doing the hoping. But neither does “It is to be hoped that,” which is the phrase that critics like Wilson Follett offer as a “natural” substitute. That’s what usage fetishism can drive you to — you cross out an adverb and replace it with a six-word impersonal passive construction, and you tell yourself you’ve improved your writing.

But the real problem with these objections is their tone-deafness. People get so worked up about the word that they can’t hear what it’s really saying. The fact is that “I hope that” doesn’t mean the same thing that “hopefully” does. The first just expresses a desire; the second makes a hopeful prediction. I’m comfortable saying, “I hope I survive to 105″ — it isn’t likely, but hey, you never know. But it would be pushing my luck to say, “Hopefully, I’ll survive to 105,” since that suggests it might actually be in the cards.

Floating modifiers may be common in English, but that does not excuse them. Given Numberg’s evident attachment to them, I am unsurprised by his assertion that “nobody objects to using ‘sadly,’ ‘mercifully,’ ‘thankfully’ or ‘frankly’ in exactly the same way.”

Nobody, Mr. Nunberg? Hardly. Anyone who cares about clarity and precision in the expression of ideas will object to such usages. A good editor would rewrite any sentence that begins with a free-floating modifier — no matter which one of them it is.

Nunberg’s defense against such rewriting is that Wilson Follett offers “It is to be hoped that” as a cumbersome, wordy substitute for “hopefully.” I assume that Nunberg refers to Follett’s discussion of “hopefully” in Modern American Usage. If so, Nunberg once again proves himself an adherent of imprecision, for this is what Follett actually says about “hopefully”:

The German language is blessed with an adverb, hoffentlich, that affirms the desirability of an occurrence that may or may not come to pass. It is generally to be translated by some such periphrasis as it is to be hoped that; but hack translators and persons more at home in German than in English persistently render it as hopefully. Now, hopefully and hopeful can indeed apply to either persons or affairs. A man in difficulty is hopeful of the outcome, or a situation looks hopeful; we face the future hopefully, or events develop hopefully. What hopefully refuses to convey in idiomatic English is the desirability of the hoped-for event. College, we read, is a place for the development of habits of inquiry, the acquisition of knowledge and, hopefully, the establishment of foundations of wisdom. Such a hopefully is un-English and eccentric; it is to be hoped is the natural way to express what is meant. The underlying mentality is the same—and, hopefully, the prescription for cure is the same (let us hope) / With its enlarged circulation–and hopefully also increased readership–[a periodical] will seek to … (we hope) / Party leaders had looked confidently to Senator L. to win . . . by a wide margin and thus, hopefully, to lead the way to victory for. . . the Presidential ticket (they hoped) / Unfortunately–or hopefully, as you prefer it–it is none too soon to formulate the problems as swiftly as we can foresee them. In the last example, hopefully needs replacing by one of the true antonyms of unfortunately–e.g. providentially.

The special badness of hopefully is not alone that it strains the sense of -ly to the breaking point, but that appeals to speakers and writers who do not think about what they are saying and pick up VOGUE WORDS [another entry in Modern American Usage] by reflex action. This peculiar charm of hopefully accounts for its tiresome frequency. How readily the rotten apple will corrupt the barrel is seen in the similar use of transferred meaning in other adverbs denoting an attitude of mind. For example: Sorrowfully (regrettably), the officials charged with wording such propositions for ballot presentation don’t say it that way / the “suicide needle” which–thankfully–he didn’t see fit to use (we are thankful to say). Adverbs so used lack point of view; they fail to tell us who does the hoping, the sorrowing, or the being thankful. Writers who feel the insistent need of an English equivalent for hoffentlich might try to popularize hopingly, but must attach it to a subject capable of hoping (op. cit., pp. 178-9).

Follett, contrary to Nunberg’s assertion, does not offer “It is to be hoped that” as a substitute for “hopefully,” which would “cross out an adverb and replace it with a six-word impersonal passive construction.” Follett gives “it is to be hoped for” as the sense of “hopefully.” But, as the preceding quotation attests, Follett is able to replace “hopefully” (where it is misused) with a few short words that take no longer to write or say than “hopefully,” and which convey the writer’s or speaker’s intended meaning more clearly. And if it does take a few extra words to say something clearly, why begrudge those words?

What about the other floating modifiers — such as “sadly,” “mercifully,” “thankfully” and “frankly” — which Nunberg defends with much passion and no logic? Follett addresses those others in the third paragraph quoted above, but he does not dispose of them properly. For example, I would not simply substitute “regrettably” for “sorrowfully”; neither is adequate. What is wanted is something like this: “The officials who write propositions for ballots should not have said … , which is misleading (vague/ambiguous).” More words? Yes, but so what? (See above.)

In any event, a writer or speaker who is serious about expressing himself clearly to an audience will never say things like “Sadly (regrettably), the old man died,” when he means either “I am (we are/they are/everyone who knew him) is saddened by (regrets) the old man’s dying,” or (less probably) “The old man grew sad as he died” or “The old man regretted dying.” I leave “mercifully,” “thankfully,” “frankly” and the rest of the overused “-ly” words as an exercise for the reader.

The aims of a writer or speaker ought to be clarity and precision, not a stubborn, pseudo-logical insistence on using a word or phrase merely because it is in vogue or (more likely) because it irritates so-called language snobs. I doubt that even the pseudo-logical “language slobs” of Nunberg’s ilk condone “like” and “you know” as interjections. But, by Nunberg’s “logic,” those interjections should be condoned — nay, encouraged — because “everyone” knows what someone who uses them is “really saying,” namely, “I am too stupid or lazy to express myself clearly and precisely.”

Literally

This is from Dana Coleman’s article “According to the Dictionary, ‘Literally’ Also Now Means ‘Figuratively’,” (Salon, August 22, 2013):

Literally, of course, means something that is actually true: “Literally every pair of shoes I own was ruined when my apartment flooded.”

When we use words not in their normal literal meaning but in a way that makes a description more impressive or interesting, the correct word, of course, is “figuratively.”

But people increasingly use “literally” to give extreme emphasis to a statement that cannot be true, as in: “My head literally exploded when I read Merriam-Webster, among others, is now sanctioning the use of literally to mean just the opposite.”

Indeed, Ragan’s PR Daily reported last week that Webster, Macmillan Dictionary and Google have added this latter informal use of “literally” as part of the word’s official definition. The Cambridge Dictionary has also jumped on board….

Webster’s first definition of literally is, “in a literal sense or matter; actually.” Its second definition is, “in effect; virtually.” In addressing this seeming contradiction, its authors comment:

“Since some people take sense 2 to be the opposition of sense 1, it has been frequently criticized as a misuse. Instead, the use is pure hyperbole intended to gain emphasis, but it often appears in contexts where no additional emphasis is necessary.”…

The problem is that a lot of people use “literally” when they mean “figuratively” because they don’t know better. It’s literally* incomprehensible to me that the editors of dictionaries would suborn linguistic anarchy. Hopefully,** they’ll rethink their rashness.

_________

* “Literally” is used correctly, though it’s superfluous here.

** “Hopefully” is used incorrectly, but in the spirit of the times.

Punctuate Properly

I can’t compete with Lynne Truss’s Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero-Tolerance Approach to Punctuation (discussed in Part Three), so I won’t try. Just read it and heed it.

But I must address the use of the hyphen in compound adjectives, and the serial comma.

Regarding the hyphen, David Bernstein of The Volokh Conspiracy writes:

I frequently have disputes with law reviewer editors over the use of dashes. Unlike co-conspirator Eugene, I’m not a grammatical expert, or even someone who has much of an interest in the subject.

But I do feel strongly that I shouldn’t use a dash between words that constitute a phrase, as in “hired gun problem”, “forensic science system”, or “toxic tort litigation.” Law review editors seem to want to generally want to change these to “hired-gun problem”, “forensic-science system”, and “toxic-tort litigation.” My view is that “hired” doesn’t modify “gun”; rather “hired gun” is a self-contained phrase. The same with “forensic science” and “toxic tort.”

Most of the commenters are right to advise Bernstein that the “dashes” — he means hyphens — are necessary. Why? To avoid confusion as to what is modifying the noun “problem.”

In “hired gun,” for example, “hired” (adjective) modifies “gun” (noun, meaning “gunslinger” or the like). But in “hired-gun problem,” “hired-gun” is a compound adjective which requires both of its parts to modify “problem.” It’s not a “hired problem” or a “gun problem,” it’s a “hired-gun problem.” The function of the hyphen is to indicate that “hired” and “gun,” taken separately, are meaningless as modifiers of “problem,” that is, to ensure that the meaning of the adjective-noun phrase is not misread.

A hyphen isn’t always necessary in such instances. But the consistent use of the hyphen in such instances avoids confusion and the possibility of misinterpretation.

The consistent use of the hyphen to form a compound adjective has a counterpart in the consistent use of the serial comma, which is the comma that precedes the last item in a list of three or more items (e.g., the red, white, and blue). Newspapers (among other sinners) eschew the serial comma for reasons too arcane to pursue here. Thoughtful counselors advise its use. (See, for example, Follett at pp. 422-3.) Why? Because the serial comma, like the hyphen in a compound adjective, averts ambiguity. It isn’t always necessary, but if it is used consistently, ambiguity can be avoided. (Here’s a great example, from the Wikipedia article linked to in the first sentence of this paragraph: “To my parents, Ayn Rand and God.” The writer means, of course, “To my parents, Ayn Rand, and God.”)

A little punctuation goes a long way.

Stand Fast against Political Correctness

As a result of political correctness, some words and phrases have gone out of favor. needlessly. Others are cluttering the language, needlessly. Political correctness manifests itself in euphemisms, verboten words, and what I call gender preciousness.

Euphemisms

These are much-favored by persons of the left, who seem unable to have an aversion to reality. Thus, for example:

- “Crippled” became “handicapped,” which became “disabled” and then “differently abled” or “something-challenged.”

- “Stupid” became “learning disabled,” which became “special needs” (a euphemistic category that houses more than the stupid).

- “Poor” became “underprivileged,” which became “economically disadvantaged,” which became “entitled” (to other people’s money), in fact if not in word.

- Colored persons became Negroes, who became blacks, then African-Americans, and now (often) persons of color.

How these linguistic contortions have helped the crippled, stupid, poor, and colored is a mystery to me. Tact is admirable, but euphemisms aren’t tactful. They’re insulting because they’re condescending.

Verboten Words

The list is long; see this and this, for example. Words become verboten for the same reason that euphemisms arise: to avoid giving offense, even where offense wouldn’t or shouldn’t be taken.

David Bernstein, writing at TCS Daily several ago, recounted some tales about political correctness. This one struck close to home:

One especially merit-less [hostile work environment] claim that led to a six-figure verdict involved Allen Fruge, a white Department of Energy employee based in Texas. Fruge unwittingly spawned a harassment suit when he followed up a southeast Texas training session with a bit of self-deprecating humor. He sent several of his colleagues who had attended the session with him gag certificates anointing each of them as an honorary Coon Ass — usually spelled coonass — a mildly derogatory slang term for a Cajun. The certificate stated that [y]ou are to sing, dance, and tell jokes and eat boudin, cracklins, gumbo, crawfish etouffe and just about anything else. The joke stemmed from the fact that southeast Texas, the training session location, has a large Cajun population, including Fruge himself.

An African American recipient of the certificate, Sherry Reid, chief of the Nuclear and Fossil Branch of the DOE in Washington, D.C., apparently missed the joke and complained to her supervisors that Fruge had called her a coon. Fruge sent Reid a formal (and humble) letter of apology for the inadvertent offense, and explained what Coon Ass actually meant. Reid nevertheless remained convinced that Coon Ass was a racial pejorative, and demanded that Fruge be fired. DOE supervisors declined to fire Fruge, but they did send him to diversity training. They also reminded Reid that the certificate had been meant as a joke, that Fruge had meant no offense, that Coon Ass was slang for Cajun, and that Fruge sent the certificates to people of various races and ethnicities, so he clearly was not targeting African Americans. Reid nevertheless sued the DOE, claiming that she had been subjected to a racial epithet that had created a hostile environment, a situation made worse by the DOEs failure to fire Fruge.

Reid’s case was seemingly frivolous. The linguistics expert her attorney hired was unable to present evidence that Coon Ass meant anything but Cajun, or that the phrase had racist origins, and Reid presented no evidence that Fruge had any discriminatory intent when he sent the certificate to her. Moreover, even if Coon Ass had been a racial epithet, a single instance of being given a joke certificate, even one containing a racial epithet, by a non-supervisory colleague who works 1,200 miles away does not seem to remotely satisfy the legal requirement that harassment must be severe and pervasive for it to create hostile environment liability. Nevertheless, a federal district court allowed the case to go to trial, and the jury awarded Reid $120,000, plus another $100,000 in attorneys fees. The DOE settled the case before its appeal could be heard for a sum very close to the jury award.

I had a similar though less costly experience some years ago, when I was chief financial and administrative officer of a defense think-tank. In the course of discussing the company’s budget during meeting with employees from across the company, I uttered “niggardly” (meaning stingy or penny-pinching). The next day a fellow vice president informed me that some of the black employees from her division had been offended by “niggardly.” I suggested that she give her employees remedial training in English vocabulary. That should have been the verdict in the Reid case.

Gender Preciousness

It has become fashionable for academicians and pseudo-serious writers to use “she” where “he” long served as the generic (and sexless) reference to a singular third person. Here is an especially grating passage from an by Oliver Cussen:

What is a historian of ideas to do? A pessimist would say she is faced with two options. She could continue to research the Enlightenment on its own terms, and wait for those who fight over its legacy—who are somehow confident in their definitions of what “it” was—to take notice. Or, as [Jonathan] Israel has done, she could pick a side, and mobilise an immense archive for the cause of liberal modernity or for the cause of its enemies. In other words, she could join Moses Herzog, with his letters that never get read and his questions that never get answered, or she could join Sandor Himmelstein and the loud, ignorant bastards (“The Trouble with the Enlightenment,” Prospect, May 5, 2013).

I don’t know about you, but I’m distracted by the use of the generic “she,” especially by a male. First, it’s not the norm (or wasn’t the norm until the thought police made it so). Thus my first reaction to reading it in place of “he” is to wonder who this “she” is; whereas, the function of “he” as a stand-in for anyone (regardless of gender) was always well understood. Second, the usage is so obviously meant to mark the writer as “sensitive” and “right thinking” that it calls into question his sincerity and objectivity.

I could go on about the use of “he or she” in place of “he” or “she.” But it should be enough to call it what it is: verbal clutter.

Then there is “man,” which for ages was well understood (in the proper context) as referring to persons in general, not to male persons in particular. (“Mankind” merely adds a superfluous syllable.)

The short, serviceable “man” has been replaced, for the most part, by “humankind.” I am baffled by the need to replaced one syllable with three. I am baffled further by the persistence of “man” — a sexist term — in the three-syllable substitute. But it gets worse when writers strain to avoid the solo use of “man” by resorting to “human beings” and the “human species.” These are longer than “humankind,” and both retain the accursed “man.”

Don’t Split Infinitives

Just don’t do it, regardless of the pleadings of descriptivists. Even Follett counsels the splitting of infinitives, when the occasion demands it. I part ways with Follett in this matter, and stand ready to be rebuked for it.

Consider the case of Eugene Volokh, a known grammatical relativist, who scoffs at “to increase dramatically” — as if “to dramatically increase” would be better. The meaning of “to increase dramatically” is clear. The only reason to write “to dramatically increase” would be to avoid the appearance of stuffiness; that is, to pander to the least cultivated of one’s readers.

Seeming unstuffy (i.e., without standards) is neither a necessary nor sufficient reason to split an infinitive. The rule about not splitting infinitives, like most other grammatical rules, serves the valid and useful purpose of preventing English from sliding yet further down the slippery slope of incomprehensibility than it has slid.

If an unsplit infinitive makes a clause or sentence seem awkward, the clause or sentence should be recast to avoid the awkwardness. Better that than make an exception that leads to further exceptions — and thence to Babel.

A Dictionary of Modern English Usage (a.k.a. Fowler’s Modern English Usage) counsels splitting an infinitive where recasting doesn’t seem to work:

We admit that separation of to from its infinitive is not in itself desirable, and we shall not gratuitously say either ‘to mortally wound’ or ‘to mortally be wounded’…. We maintain, however, that a real [split infinitive], though not desirable in itself, is preferable to either of two things, to real ambiguity, and to patent artificiality…. We will split infinitives sooner than be ambiguous or artificial; more than that, we will freely admit that sufficient recasting will get rid of any [split infinitive] without involving either of those faults, and yet reserve to ourselves the right of deciding in each case whether recasting is worth while. Let us take an example: ‘In these circumstances, the Commission … has been feeling its way to modifications intended to better equip successful candidates for careers in India and at the same time to meet reasonable Indian demands.’… What then of recasting? ‘intended to make successful candidates fitter for’ is the best we can do if the exact sense is to be kept… (p. 581, Second Edition).

Good try, but not good enough. This would do: “In these circumstances, the Commission … has been considering modifications that would better equip successful candidates for careers in India and at the same time meet reasonable Indian demands.”

Enough said? I think so.

* * *

Some readers may conclude that I prefer stodginess to liveliness. That’s not true, as any discerning reader of this blog will know. I love new words and new ways of using words, and I try to engage readers while informing and persuading them. But I do those things within the expansive boundaries of prescriptive grammar and usage. Those boundaries will change with time, as they have in the past. But they should change only when change serves understanding, not when it serves the whims of illiterates and language anarchists.