I often refer to social norms — long-standing and voluntarily evolved — as the bedrock of a truly libertarian order. This page serves as a permanent home for my views about social norms. It includes a long list of posts about social norms, liberty, libertarianism, and the destructive role of government.

Category: Liberty – Libertarianism – Rights

The Beginning of the End of Liberty in America

SEVERAL ITEMS HAVE BEEN ADDED TO THE LIST OF RELATED READINGS SINCE THE INITIAL PUBLICATION OF THIS POST ON 06/26/15

Winston Churchill, speaking in November 1942 about the victory of the Allies in the Second Battle of El Alamein, said this:

This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.

We may have reached the end of the legal battle over same-sex “marriage” with today’s decision by five justices of the Supreme Court in the case of Obergefell v. Hodges. But that decision probably also marks the beginning of the end of liberty in America.

Consider these passages from Chief Justice Roberts’s dissent (citations omitted):

…Today’s decision … creates serious questions about religious liberty. Many good and decent people oppose same-sex marriage as a tenet of faith, and their freedom to exercise religion is—unlike the right imagined by the majority—actually spelled out in the Constitution.

Respect for sincere religious conviction has led voters and legislators in every State that has adopted same-sex marriage democratically to include accommodations for religious practice. The majority’s decision imposing same-sex marriage cannot, of course, create any such accommodations. The majority graciously suggests that religious believers may continue to “advocate” and “teach” their views of marriage…. The First Amendment guarantees, however, the freedom to “exercise” religion. Ominously, that is not a word the majority uses.

Hard questions arise when people of faith exercise religion in ways that may be seen to conflict with the new right to same-sex marriage—when, for example, a religious college provides married student housing only to opposite-sex married couples, or a religious adoption agency declines to place children with same-sex married couples. Indeed, the Solicitor General candidly acknowledged that the tax exemptions of some religious institutions would be in question if they opposed same-sex marriage…. There is little doubt that these and similar questions will soon be before this Court. Unfortunately, people of faith can take no comfort in the treatment they receive from the majority today.

Perhaps the most discouraging aspect of today’s decision is the extent to which the majority feels compelled to sully those on the other side of the debate. The majority offers a cursory assurance that it does not intend to disparage people who, as a matter of conscience, cannot accept same-sex marriage…. That disclaimer is hard to square with the very next sentence, in which the majority explains that “the necessary consequence” of laws codifying the traditional definition of marriage is to “demea[n]or stigmatiz[e]” same-sex couples…. The majority reiterates such characterizations over and over. By the majority’s account, Americans who did nothing more than follow the understanding of marriage that has existed for our entire history—in particular, the tens of millions of people who voted to reaffirm their States’ enduring definition of marriage—have acted to “lock . . . out,” “disparage,”“disrespect and subordinate,” and inflict “[d]ignitary wounds” upon their gay and lesbian neighbors…. These apparent assaults on the character of fair minded people will have an effect, in society and in court…. Moreover, they are entirely gratuitous. It is one thing for the majority to conclude that the Constitution protects a right to same-sex marriage; it is something else to portray everyone who does not share the majority’s “better informed understanding” as bigoted….

Justice Alito puts it more plainly:

[Today’s decision] will be used to vilify Americans who are unwilling to assent to the new orthodoxy. In the course of its opinion,the majority compares traditional marriage laws to laws that denied equal treatment for African-Americans and women…. The implications of this analogy will be exploited by those who are determined to stamp out every vestige of dissent.

Perhaps recognizing how its reasoning may be used, the majority attempts, toward the end of its opinion, to reassure those who oppose same-sex marriage that their rights of conscience will be protected…. We will soon see whether this proves to be true. I assume that those who cling to old beliefs will be able to whisper their thoughts in the recesses of their homes, but if they repeat those views in public, they will risk being labeled as bigots and treated as such by governments, employers, and schools….

…By imposing its own views on the entire country, the majority facilitates the marginalization of the many Americans who have traditional ideas. Recalling the harsh treatment of gays and lesbians in the past, some may think that turnabout is fair play. But if that sentiment prevails, the Nation will experience bitter and lasting wounds.

Erick Erickson drives it home:

Make no mistake — this is not the end of a march, but the beginning of a new march. You will be made to care. You will be forced to pick a side. Should you pick the side of traditional marriage, you can expect left to be ruthless. After all, the Supreme Court has said gay marriage is a not just a right, but a fundamental right. [“The Supremes Decide,” RedState, June 26, 2015]

Erickson counsels civil disobedience:

It’s time to defy the court on this. It’s time to fight back. Nonviolent civil disobedience is the only option we have been left under this terrible ruling. We will be heard. [“It’s Time for Civil Disobedience,” RedState, June 26, 2015]

Most citizens will, of course, attempt to exercise their freedom of speech, and many business owners will, of course, attempt to exercise their freedom of association. But for every person who insists on exercising his rights, there will be at least as many (and probably more) who will be cowed, shamed, and forced by the state into silence and compliance with the new dispensation. And the more who are cowed, shamed, and forced into silence and compliance, the fewer who will assert their rights. Thus will the vestiges of liberty vanish.

That’s how it looks from here on this new day of infamy.

* * *

Related reading:

- streiff, “Obergefell and the Roadmap to Drive Christianity from the Public Square,” RedState, June 27, 2015 (Christianity isn’t the only target; anyone who challenges the legality and propriety of gay “marriage” is in the cross-hairs of the Gaystapo and it enablers.)

- Scott Johnson, “The Need to Get Our Minds Right,” Power Line, June 28, 2015

- F.H. Buckley, “Take Heart, Conservatives!,” The American Spectator, June 29, 2015 (an amusing but not reassuring take on Obergefell v. Hodges)

- Erick Erickson, “What Actually Comes Next,” RedState, June 29, 2015

- Christopher Freiman, “Indeed, Why Not Polygamy?,” Bleeding Heart Libertarians, June 29, 2015

- Jennifer Kabbanny, “Conservative Professors React to Same-Sex Marriage Decision,” The College Fix, June 29, 2015

- Stella Morabito, “15 Reasons Why ‘Marriage Equality’ Is about Neither Marriage Nor Equality,” The Federalist, June 29, 2015

- Keith Preston, “Gay Marriage, Good News and Bad: Some Thoughts on ‘Marriage Equality’,” The Libertarian Alliance Blog, June 29, 2015

- Bill Valicella, “Why Not Privatize Marriage?,” Maverick Philosopher, June 29, 2015

- Ryan T. Anderson, “In Depth: 4 Harms the Court’s Marriage Ruling Will Cause,” The Daily Signal, June 30, 2015

- Adam Freedman, “Obergefell’s Threat to Religious Liberty,” City Journal, July 1, 2015

- Kelsey Harkness, “State Silences Bakers Who Refused to Make Cake for Lesbian Couple, Fines Them $135K,” The Daily Signal, July 2, 2015

- Andrew Hyman, “George Will Turns James Madison’s Words Upside Down and Inside Out and Backwards Too,” The Originalism Blog, July 2, 2015

- Daniel J. Flynn, “America Was,” The American Spectator, July 3, 2015

- Tom Nichols, “The New Totalitarians Are Here,” The Federalist, July 6, 2015

- Flagg Taylor, “Thought Control’s Lingua Franca,” Library of Law and Liberty, July 8, 2015

- Hans von Spakovsky, “Oregon’s War on the Christian Bakers’ Free Speech,” The Daily Signal, July 18, 2015

* * *

Related posts:

The Marriage Contract

Libertarianism, Marriage, and the True Meaning of Family Values

Same-Sex Marriage

“Equal Protection” and Homosexual Marriage

Marriage and Children

Civil Society and Homosexual “Marriage”

The Constitution: Original Meaning, Corruption, and Restoration

Perry v. Schwarzenegger, Due Process, and Equal Protection

Rationalism, Social Norms, and Same-Sex “Marriage”

Asymmetrical (Ideological) Warfare

In Defense of Marriage

A Declaration of Civil Disobedience

The Myth That Same-Sex “Marriage” Causes No Harm

Liberty and Society

The View from Here

The Culture War

Surrender? Hell No!

Posner the Fatuous

Getting “Equal Protection” Right

The Writing on the Wall

How to Protect Property Rights and Freedom of Association and Expression

The Gaystapo at Work

The Gaystapo and Islam

The Principles of Actionable Harm

I prefer — as a minarchistic libertarian (a radical-right-minarchist, to be precise) — an accountable, constrained state to the the condition of anarchy. This leads to warlordism and thence to despotism. But the state must be held to its proper realm of action, namely, dispensing justice and defending citizens. Its purpose in doing those things — and the sole justification for its being — is to protect negative rights (including property rights) and civil society. (For more about the proper role of the state, go to “Parsing Political Philosophy” and under the section headed “Minarchism,” see “The Protection of Negative Rights,” “More about Property Rights,” and the “Role of Civil Society.”)

Specifically:

1. An actionable harm — a harm against which the state may properly act — is one that deprives a person of negative rights or undermines the voluntarily evolved institutions and norms of civil society.

2. The state should not act — or encourage action by private entities — except as it seeks to deter, prevent, or remedy an actionable harm to its citizens.

3. An actionable harm may be immediate (as in the case of murder) or credibly threatened (as in the case of a conspiracy to commit murder). But actionable harms extend beyond those that are immediate or credibly threatened. They also result from actions by the state that strain and sunder the bonds of trust that make it possible for a people to coexist civilly, through the mutual self-restraint that arises from voluntarily evolved social norms. The use of state power has deeply eroded such norms. The result has been to undermine the trust and self-restraint that enable a people to enjoy liberty and its fruits; for example:

- Affirmative action and other forms of forced racial integration deny property rights and freedom of association, prolong racial animosity, and impose unwarranted economic harm on those who are guilty of nothing but the paleness of their skin.

- Abortion suborns infanticide and invites euthanasia of the infirm and elderly.

- The legal enshrinement of gay rights leads to the suppression of speech and the denial of freedoms of expression and association, at the expense of citizens who have done nothing worse than refuse to recognize a “lifestyle choice” of which they disapprove, as should be their right.

- State recognition of gay marriage undermines heterosexual marriage — an essential civilizing institution.

- Amnesties for illegal immigrants impose heavy economic costs on Americans and enlarge the constituency for big government.

4. An expression of thought cannot be an actionable harm unless it

a. is defamatory; or

b. would directly obstruct governmental efforts to deter, prevent, or remedy an actionable harm (e.g., divulging classified defense information, committing perjury); or

c. intentionally causes or would directly cause an actionable harm (e.g., plotting to commit an act of terrorism, forming a lynch mob); or

d. purposely — through a lie or the withholding of pertinent facts — causes a person to act against self-interest; or

e. purposely — through its intended influence on government — results in what would be an actionable harm if committed by a private entity (e.g., the taking of income from persons who earn it, simply to assuage the envy of those who earn less). (The remedy for such harms should not be the suppression or punishment of the harmful expressions; the remedy should be the enactment and enforcement of restrictions on the ability of government to act as it does.)

5. With those exceptions, a mere statement of fact, belief, opinion, or attitude cannot be an actionable harm. Otherwise, those persons who do not care for the facts, beliefs, opinions, or attitudes expressed by other persons would be able to stifle speech they find offensive merely by claiming to be harmed by it. And those persons who claim to be offended by the superior income or wealth of other persons would be entitled to recompense from those other persons. (It takes little imagination to see the ramifications of such thinking; rich heterosexuals, for example, could claim to be offended by the existence of persons who are poor or homosexual, and could demand their extermination as a remedy.)

6. It cannot be an actionable harm to commit a private, voluntary act of omission (e.g., the refusal of social or economic relations for reasons of personal preference), other than a breach of contract or fiduciary responsibility. Nor can it be an actionable harm to commit a private, voluntary act which does nothing more than arouse resentment, envy, or anger in others. A legitimate state does not judge, punish, or attempt to influence private, voluntary acts that are not otherwise actionable harms.

7. By the same token, a legitimate state does not judge, punish, or attempt to influence private, voluntary acts of commission which have undesirable but avoidable consequences. For example:

- Government prohibition of smoking on private property is illegitimate because non-smokers could choose not to frequent or work at establishments that allow smoking.

- Other government restrictions on the use of private property (e.g., laws that bar restrictive covenants or mandate public accommodation) are illegitimate because they (1) diminish property rights and (2) discourage ameliorating activities (e.g., the evolution away from cultural behaviors that play into racial prejudice, investments in black communities and black-run public accommodations).

- Tax-funded subsidies for retirement and health care are illegitimate because they discourage hard work, saving, and other prudent habits — habits that would lead to less dependence on government, were those habits encouraged.

8. It is also wrong for the state to make and enforce distinctions among individuals that have the effect of advantaging some persons because of their age, gender, sexual orientation, skin color, ethnicity, religion, or economic status.

9. Except in the case of punishment for an actionable harm, it is an actionable harm to bar a competent adult from

a. expressing his views, as long as they are not defamatory or meant to incite harm (voice); or

b. moving to a place of his choosing (exit).

(As a practical matter, voice is of little consequence if the state’s power of the lives and livelihoods of citizens has grown so great that it cannot be undone except by revolution. Further, exit becomes meaningless when the central government’s power reaches into every corner of the nation and leaves persons of ordinary means with no place to turn. In the present circumstances, it follows that the state daily commits actionable harms against citizens of the United States.)

10. The proper role of the state is to enforce the preceding principles. In particular,

a. to remain neutral with respect to evolved social norms, except where those norms deny voice or exit, as with the systematic disenfranchisement or enslavement of particular classes of persons; and

b. to foster economic freedom (and therefore social freedom) by ensuring open trade within the nation and (to the extent compatible with national security) open trade with (but selective immigration from) other nations; and

c. to ensure free expression of thought, except where such expression is tantamount to an actionable harm (as in a conspiracy to commit murder or mount a campaign of harassment); and

d. to see that just laws — those enacted in accordance with the principles of actionable harm — are enforced swiftly and surely, with favoritism toward no person or class of persons; and

e. to defend citizens against predators, foreign and domestic.

* * *

The principles of actionable harm are not rules for making everyone happy. They are rules for ensuring that each of us is able to pursue happiness without impinging on the happiness of others.

The state should apply the principles of actionable harm only to citizens and legitimate residents of the United States. Sovereignty is otherwise meaningless; the United States exists for the protection of citizens and persons legitimately resident; it is not an eleemosynary institution.

By the same token, those who would harm citizens and legitimate residents of the United States must be treated summarily and harshly, as necessary.

* * *

Related posts:

Why Sovereignty?

Parsing Political Philosophy

Negative Rights

Negative Rights, Social Norms, and the Constitution

Rights, Liberty, the Golden Rule, and the Legitimate State

The Golden Rule and the State

The Meaning of Liberty

Positive Liberty vs. Liberty

Facets of Liberty

Liberty and Society

The Eclipse of “Old America”

Genetic Kinship and Society

Liberty as a Social Construct: Moral Relativism?

Defending Liberty against (Pseudo) Libertarians

Defining Liberty

Conservatism as Right-Minarchism

Parsing Political Philosophy (II)

Getting Liberty Wrong

Romanticizing the State

Libertarianism and the State

My View of Libertarianism

No Wonder Liberty Is Disappearing

I just took the Freedom Scenarios Inventory at YourMorals.org, the producers of which include the estimable Jonathan Haidt. I was shocked by the result — not my result, but my result in comparison with the results obtained by other users.

Before you look at the result, you should read this description of the test:

The scale is a measure of the degree to which people consider different freedom issues to be morally relevant. As you may have noticed, this inventory does not include perennially contentious freedom-related issues like abortion or gun rights. These issues were deliberately excluded from this scale, because we are interested in what drives people to be concerned with freedom issues in general. On the other hand, people’s stances on well worn political issues like abortion and gun control are likely to be influenced more by their political beliefs rather than their freedom concerns.

The idea behind the scale is to determine how various individual difference variables relate to people’s moral freedom concerns. Throughout the world, calls for freedom and liberty are growing louder. We want to begin to investigate what is driving this heightened concern for freedom. Surprisingly little research has investigated the antecedents of freedom concerns. In the past, our group has investigated clusters of characteristics associated with groups of people who are more concerned with liberty (i.e., libertarians), but this type of investigation differs from the current investigation in that we are now interested more in individual differences in freedom concerns – not group differences…. It seems that many psychologists assume that many types of freedom concerns are driven by a lack of empathy for others, but we think the truth is more complicated than this.

The test-taker is asked to rate each of 14 scenarios on the following scale:

0 – Not at all morally bad

1 – Barely morally bad

2 – Slightly morally bad

3 – Somewhat morally bad

4 – Morally bad

5 – Very morally bad

6 – Extremely morally bad

7 – Extraordinarily morally bad

8 – Nothing could be more morally bad

Here are the 14 scenarios, which I’ve numbered for ease of reference:

1. You are no longer free to eat your favorite delicious but unhealthy meal due to the government’s dietary restrictions.

2. You are no longer free to always spend your money in the way you want.

3. You are not always free to wear whatever you want to wear. Some clothes are illegal.

4. Your favorite source of entertainment is made illegal.

5. Your favorite hobby is made illegal.

6.. You are not free to live where you want to live.

7. By law, you must sleep one hour less each day than you would like.

8. You are no longer free to eat your favorite dessert food (because the government has deemed it unhealthy).

9. You are no longer allowed to kill innocent people . [Obviously thrown in to see if you’re paying attention.]

10. You are no longer free to spend as much time as you want watching television/movies/video clips due to government restrictions.

11, You are no longer free to drink your favorite beverage, because the government considers it unhealthy.

12. You are no longer free to drive whenever you want for however long you want due to driving restrictions.

13. You are no longer free to go to your favorite internet site.

14. You are no longer free to go to any internet site you choose to go to.

I didn’t expect to be unusual in my views about freedom. But it seems that I am:

A lot of people — too many — are willing to let government push them around. Why? Because Big Brother knows best? Because freedom isn’t worth fighting for? Because of the illusion of security and prosperity created by the regulatory-welfare state? Whatever the reason, the evident willingness of test-takers to accede to infringements of their liberty is frightening.

The result confirms my view that democracy is an enemy of liberty.

* * *

Related posts:

Something Controversial

More about Democracy and Liberty

Yet Another Look at Democracy

Democracy and the Irrational Voter

The Ruinous Despotism of Democracy

Democracy and Liberty

The Interest-Group Paradox

About Democracy

“The Great Debate”: Not So Great

I was drawn to Yuval Levin‘s The Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the Birth of Right and Left because some commentators on the right had praised it. But I was disappointed by The Great Debate for two reasons: repetitiveness and wrongheadedness (with respect to conservatism).

Regarding repetitiveness, the philosophical differences between Burke and Paine are rather straightforward and can be explained in a brief essay. Levin’s 304 pages strike me as endless variations on a simple theme — a literary equivalent of Philip Glass‘s long-winded minimalism.

In fact, I am wrong to suggest that it would take only a brief essay to capture the philosophical differences between Burke and Paine. Levin does it in a few paragraphs:

Paine lays out his political vision in greater detail in Rights of Man than in any of his earlier writings: a vision of individualism, natural rights, and equal justice for all made possible by a government that lives up to true republican ideals. [Kindle edition, p. 34]

* * *

Politics [to Burke] was first and foremost about particular people living together , rather than about general rules put into effect. This emphasis caused Burke to oppose the sort of liberalism expounded by many of the radical reformers of his day. They argued in the parlance of natural rights drawn from reflections on an individualist state of nature and sought to apply the principles of that approach directly to political life. [Op. cit., p. 11]

* * *

For Paine, the natural equality of all human beings translates to complete political equality and therefore to a right to self-determination. The formation of society was itself a choice made by free individuals, so the natural rights that people bring with them into society are rights to act as one chooses, free of coercion. Each person should have the right to do as he chooses unless his choices interfere with the equal rights and freedoms of others. And when that happens— when society as a whole must act through its government to restrict the freedom of some of its members— government can only act in accordance with the wishes of the majority, aggregated through a political process. Politics, in this view, is fundamentally an arena for the exercise of choice, and our only real political obligations are to respect the freedoms and choices of others.

For Burke, human nature can only be understood within society and therefore within the complex web of relations in which every person is embedded. None of us chooses the nation, community, or family into which we are born, and while we can choose to change our circumstances to some degree as we get older, we are always defined by some crucial obligations and relationships not of our own choosing. A just and healthy politics must recognize these obligations and relationships and respond to society as it exists, before politics can enable us to make changes for the better. In this view, politics must reinforce the bonds that hold people together, enabling us to be free within society rather than defining freedom to the exclusion of society and allowing us to meet our obligations to past and future generations, too. Meeting obligations is as essential to our happiness and our nature as making choices. [Op cit., pp. 91-92]

In sum, Paine is the quintessential “liberal” (leftist), that is, a rationalistic ideologue who has a view of the world as it ought to be.* And it is that view which governments should serve, or be overthrown. Burke, on the other hand, is a non-ideologue. Social arrangements — including political and economic ones — are emergent. Michael Oakeshott, a latter-day Burkean, puts it this way:

Government, … as the conservative … understands it, does not begin with a vision of another, different and better world, but with the observation of the self-government practised even by men of passion in the conduct of their enterprises; it begins in the informal adjustments of interests to one another which are designed to release those who are apt to collide from the mutual frustration of a collision. Sometimes these adjustments are no more than agreements between two parties to keep out of each other’s way; sometimes they are of wider application and more durable character, such as the International Rules for for the prevention of collisions at sea. In short, the intimations of government are to be found in ritual, not in religion or philosophy; in the enjoyment of orderly and peaceable behaviour, not in the search for truth or perfection….

To govern, then, as the conservative understands it, is to provide a vinculum juris for those manners of conduct which, in the circumstances, are least likely to result in a frustrating collision of interests; to provide redress and means of compensation for those who suffer from others behaving in a contrary manners; sometimes to provide punishment for those who pursue their own interests regardless of the rules; and, of course, to provide a sufficient force to maintain the authority of an arbiter of this kind. Thus, governing is recognized as a specific and limited activity; not the management of an enterprise, but the rule of those engaged in a great diversity of self-chosen enterprises. It is not concerned with concrete persons, but with activities; and with activities only in respect of their propensity to collide with one another. It is not concerned with moral right and wrong, it is not designed to make men good or even better; it is not indispensable on account of ‘the natural depravity of mankind’ but merely because of their current disposition to be extravagant; its business is to keep its subjects at peace with one another in the activities in which they have chosen to seek their happiness. And if there is any general idea entailed in this view, it is, perhaps, that a government which does not sustain the loyalty of its subjects is worthless; and that while one which (in the old puritan phrase) ‘commands the truth’ is incapable of doing so (because some of its subjects will believe its ‘truth’ to be in error), one which is indifferent to ‘truth’ and ‘error’ alike, and merely pursues peace, presents no obstacle to the necessary loyalty.

…[A]s the conservative understands it, modification of the rules should always reflect, and never impose, a change in the activities and beliefs of those who are subject to them, and should never on any occasion be so great as to destroy the ensemble. Consequently, the conservative will have nothing to do with innovations designed to meet merely hypothetical situations; he will prefer to enforce a rule he has got rather than invent a new one; he will think it appropriate to delay a modification of the rules until it is clear that the change of circumstances it is designed to reflect has come to stay for a while; he will be suspicious of proposals for change in excess of what the situation calls for, of rulers who demand extra-ordinary powers in order to make great changes and whose utterances re tied to generalities like ‘the public good’ or social justice’, and of Saviours of Society who buckle on armour and seek dragons to slay; he will think it proper to consider the occasion of the innovation with care; in short, he will be disposed to regard politics as an activity in which a valuable set of tools is renovated from time to time and kept in trim rather than as an opportunity for perpetual re-equipment. [Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays, New and Expanded Edition, pp. 427-31]

This leads me to Levin’s wrongheadedness with respect to conservatism. It surfaces in the final chapter, with a failed attempt to reconcile the philosophies of Burke and Paine as variants of what Levin calls liberalism.

Given the stark differences between Paine’s proto-liberalism and Burkean conservatism, I cannot view the latter as a mere variant of the former. As Levin says,

the Burke-Paine debate is about Enlightenment liberalism, whose underlying worldview unavoidably raises the problem of the generations. Enlightenment liberalism emphasizes government by consent, individualism, and social equality, all of which are in tension with some rather glaring facts of the human condition : that we are born into a society that already exists, that we enter this society without consenting to it, that we enter it with social connections and not as isolated individuals, and that these connections help define our place in society and therefore often raise barriers to equality.** [Op. cit., p. 206]

Despite that, Levin writes of

[t]he tradition of conservative liberalism — the gradual accumulation of practices and institutions of freedom and order that Burke celebrated as the English constitution….

… [T]his very same conservative liberalism is very frequently the vision [that today’s conservatives] pursue in practice. It is the vision conservatives advance when they defend traditional social institutions and the family, seek to make our culture more hospitable to children, and rail against attempts at technocratic expert government. It is the vision they uphold when they insist on an allegiance to our forefathers’ constitutional forms, warn of the dangers of burdening our children with debt to fund our own consumption, or insist that the sheer scope and ambition of our government makes it untenable. [Op. cit., p. 229]

Levin’s sleight of hand is subtle. Paine’s so-called liberalism rests on premises rejected by Burke, the most important of which is that change can and should be imposed from the top down, through representative government. Where conservatives do promote change from the top down, it is to push civil society toward the status quo ante, wherein change was gradual and bottom-up, driven by the necessities of peaceful, beneficial coexistence. That isn’t liberalism; it’s conservatism, pure and simple.

Whence Levin’s category error? It seems to arise from Levin’s mistaken belief in an all-embracing social will. After all, if humankind has a collective will, its various political philosophies can be thought of as manifestations of an underlying bent. And that bent, in Levin’s view, might as well be called “liberalism.” It would be no less arbitrary to call it Couéism, or to say that pigs are human beings because they breathe air.

Am I being too harsh? Not at all. Consider the following passage from The Great Debate, with my interpolations in brackets:

The tension between those two dispositions comes down to some very basic questions: Should our society be made to answer [by whom] to the demands of stark and abstract commitments to ideals like social equality or to the patterns of its own concrete political traditions and foundations? Should the citizen’s relationship to his society be defined [by whom] above all by the individual right of free choice or by a web of obligations and conventions not entirely of our own choosing? Are great public problems best addressed through institutions designed to apply the explicit technical knowledge of experts or by those designed to channel the implicit social knowledge of the community? Should we [who?] see each of our society’s failings [by whose standards?] as one large problem to be solved by comprehensive transformation or as a set of discrete imperfections to be addressed by building on what works tolerably well to address what does not? What authority should the character of the given world exercise over our sense of what we would like it to be? [The opacity of the preceding sentence should be a clue about Levin’s epistemic confusion.] …

Our answers [as individuals] will tend to shape how we [as individuals] think about particular political questions. Do we [sic] want to fix our [sic] health-care system by empowering expert panels armed with the latest effectiveness data to manage the system from the center or by arranging economic incentives to channel consumer knowledge and preferences and address some of the system’s discrete problems? [Or simply by non-interference with markets?] Do we [sic] want to alleviate poverty through large national programs that use public dollars to supplement the incomes of the poor or through efforts to build on the social infrastructure of local civil-society institutions to help the poor build the skills and habits to rise? [Or by fostering personal responsibility and self-reliance through laissez-faire, with private charity for the “hard cases”?] Do we [who?] want problems addressed through the most comprehensive and broadest possible means or through the most minimal and targeted ones? [Or through voluntary cooperation?] …

…Is liberalism, in other words, a theoretical discovery to be put into effect or a practical achievement to be reinforced and perfected? [By who?] These two possibilities [see below] suggest two rather different sorts of liberal politics: a politics of vigorous progress toward an ideal goal or a politics of preservation and perfection of a precious inheritance. They suggest, in other words, a progressive liberalism and a conservative liberalism. [Op. cit., pp. 226-227]

Even though liberals tout individualism, they evince a (mistaken) belief in a collective conscience. Individualism, in the liberal worldview, is permissible only to the extent that it advances liberals’ values du jour. There is no room in liberalism for liberty, which is

peaceful, willing coexistence and its concomitant: beneficially cooperative behavior.

Why is there no room in liberalism for liberty? Because peaceful, willing coexistence might not lead to the particular outcomes that liberals value — for the moment.

In sum, liberalism, despite its name, is an enemy of liberty. And Paine proves his liberal credentials when, in Levin’s words, he

makes a forceful case for something like a modern welfare system. In so doing, Paine helps show how the modern left developed from Enlightenment liberalism toward embryonic forms of welfare-state liberalism as its utopian political hopes seemed dashed by the grim realities of the industrial revolution. [Op. cit., p. 120]

“The grim realities of the industrial revolution” are that workers’ real incomes rose, albeit gradually. Levin evidently belongs to the romantic-rustic school of thought that equates factories with misery and squalor and overlooks the deeper misery and squalor of peasantry.

I don’t know what school of conservative thought Levin belongs to, but it can’t the school of thought represented by Burke, Oakeshott, and Hayek. If it were, Levin wouldn’t deploy the absurd term “conservative liberalism.”

__________

* In that respect, there is no distance at all between Paine and his pseudo-libertarian admirers (e.g., here). Their mutual attachment to “natural rights” lends them an air of moral superiority, but it is made of air.

** Not to mention the obvious fact that human beings are not equal in any way, except rhetorically. Some would say that they are equal before the laws of the United States, which is true only in theory. Laws are not applied evenhandedly, especially including laws that are meant to confer “equality” on specified groups but which then accord privileges that deprive others of jobs, promotions, admissions, and speech and property rights (e.g., affirmative action, low-income mortgages, and various anti-discrimination statutes).

* * *

Related posts:

The Social Welfare Function

On Liberty

Inventing “Liberalism”

What Is Conservatism?

Utilitarianism vs. Liberty

Accountants of the Soul

The Left

Enough of “Social Welfare”

Undermining the Free Society

Pseudo-Libertarian Sophistry vs. True Libertarianism

Our Enemy, the State

Positivism, “Natural Rights,” and Libertarianism

“Intellectuals and Society”: A Review

What Are “Natural Rights”?

Government vs. Community

Libertarian Conservative or Conservative Libertarian?

Bounded Liberty: A Thought Experiment

The Left’s Agenda

Evolution, Human Nature, and “Natural Rights”

More Pseudo-Libertarianism

More about Conservative Governance

The Meaning of Liberty

Positive Liberty vs. Liberty

The Evil That Is Done with Good Intentions

Understanding Hayek

The Left and Its Delusions

The Destruction of Society in the Name of “Society”

About Democracy

True Libertarianism, One More Time

Human Nature, Liberty, and Rationalism

More Pseudo-Libertarianism

Bounded Liberty: A Thought Experiment

A Declaration and Defense of My Prejudices about Governance

Society and the State

Why Conservatism Works

Liberty and Society

Tolerance on the Left

The Eclipse of “Old America”

Genetic Kinship and Society

Liberty as a Social Construct: Moral Relativism?

Defending Liberty against (Pseudo) Libertarians

The Barbarians Within and the State of the Union

Defining Liberty

Government Failure Comes as a Shock to Liberals

“We the People” and Big Government

The Futile Search for “Natural Rights”

The Pseudo-Libertarian Temperament

Parsing Political Philosophy (II)

Modern Liberalism as Wishful Thinking

Getting Liberty Wrong

Romanticizing the State

“Liberalism” and Personal Responsibility

My View of Libertarianism

Parsing Political Philosophy (II)

The Writing on the Wall

A headline at Slate puts it this way: “The Supreme Court Just Admitted It’s Going to Rule in Favor of Marriage Equality.” Which is to say that when it comes to the legalization of same-sex “marriage”* across the United States, the writing is on the wall.

Here are some relevant passages from the Slate story:

Early Monday morning [February 9[, the Supreme Court refused to stay a federal judge’s order invalidating Alabama’s ban on same-sex marriage….

Here’s how Monday’s decision reveals the justices’ intention to strike down gay marriage bans across the country. Typically, the justices will stay any federal court ruling whose merits are currently under consideration by the Supreme Court. Under normal circumstances, that is precisely what the court would have done here: The justices will rule on the constitutionality of state-level marriage bans this summer, so they might as well put any federal court rulings on hold until they’ve had a chance to say the last word. After all, if the court ultimately ruled against marriage equality, the Alabama district court’s order would be effectively reversed, and those gay couples who wed in the coming months would find their unions trapped in legal limbo.

But that is not what the court did here. Instead, seven justices agreed, without comment, that the district court’s ruling could go into effect, allowing thousands of gay couples in Alabama to wed. That is not what a court that planned to rule against marriage equality would do. By permitting these marriages to occur, the justices have effectively tipped their hand, revealing that any lower court’s pro-gay ruling will soon be affirmed by the high court itself.

Don’t believe me? Then ask Justice Clarence Thomas, who, along with Justice Antonin Scalia, dissented from Monday’s denial of a stay…. The court’s “acquiescence” to gay marriage in Alabama, Thomas wrote, “may well be seen as a signal of the Court’s intended resolution” of the constitutionality of gay marriage bans….

I suspect that Justice Thomas has it right. (I only hope that the acquiescence of Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Alito is part of a tacit deal in which their support for “marriage equality” is repaid by the evisceration of Obamacare when the Court rules in King v. Burwell.) The Court’s refusal to stay same-sex “marriage” in Alabama seems to be the writing on the wall — the foreshadowing of the Court’s decision in four related same-sex “marriage” cases.

If the Court, as now expected, rules for “marriage equality” under the rubric of “equal protection,” that will only mark the beginning of a push for other kinds of “equality.” What’s next? Here are my guesses:

- How can polygamy fail to gain legal acceptance if the “partners” are willing adults?

- Ditto incestuous marriage.

- Then comes bestiality, but perhaps limited in some degree by the bestowal of constitutional rights for animals.

- When that’s done, the Court’s views will have evolved to the point of allowing pederasty at the urging of NAMBLA.

Fuddy-duddies — like this one — who oppose the legalization of moral corruption will be silenced by the threat of fines and imprisonment.

Livy, the Roman historian, says this in the introduction to his history of Rome:

The subjects to which I would ask each of my readers to devote his earnest attention are these – the life and morals of the community; the men and the qualities by which through domestic policy and foreign war dominion was won and extended. Then as the standard of morality gradually lowers, let him follow the decay of the national character, observing how at first it slowly sinks, then slips downward more and more rapidly, and finally begins to plunge into headlong ruin, until he reaches these days, in which we can bear neither our diseases nor their remedies.

Livy foretold the fate of the Roman Empire. And I fear that he has also foretold the fate of the American Republic.

The writing is on the wall.

__________

* Why the “sneer quotes”? See “Notes about Usage” in the sidebar.

* * *

Related posts:

Same-Sex Marriage

“Equal Protection” and Homosexual Marriage

Civil Society and Homosexual “Marriage”

Rationalism, Social Norms, and Same-Sex “Marriage”

In Defense of Marriage

The Myth That Same-Sex “Marriage” Causes No Harm

Abortion, “Gay Rights,” and Liberty

The Equal-Protection Scam and Same-Sex “Marriage”

Not-So-Random Thoughts (VIII) (first item)

The View from Here

The Culture War

The Fall and Rise of American Empire

O Tempora O Mores!

Murder Is Constitutional

Posner the Fatuous

Getting “Equal Protection” Right

Tolerance

Bryan Caplan struggles to define tolerance. This seems to be what he’s searching for:

a disposition to allow freedom of choice and behavior

TheFreeDictionary.com, Thesaurus, Noun, 2

With that definition in mind, I’ll address the reasons given by Caplan for practicing tolerance:

1. People’s moral objections to how other people use their own person and property are usually greatly overstated – or simply wrong. Think about how often people sneer at the way others dress, talk, or even walk. Think about how often people twist personality clashes into battles of good versus evil. From a calm, detached point of view, most of these complaints are simply silly.

The link points to a post in which Caplan confesses his own immature silliness. What’s missing are the “complaints” that are not “simply silly.” Take abortion, for example. It’s a practice that’s often defended on pseudo-libertarian grounds: a patently contrived right to privacy, for example. Caplan is cagey about abortion. If he is opposed to it, his reasons seem utilitarian rather than moral. In any event, opposition to abortion is not mere silliness; it is based on a profound moral objection to murder.

Nor should so-called personality clashes be dismissed as silliness. For example, during my 30 years as an analyst and manager at a major defense think-tank, I was a party to five conflicts (lasting months and years) that ignorant bystanders might have called personality clashes (and some bystanders did just that). But all five conflicts involved substantive differences about management methods, business ethics, or contractual performance.

Contra Caplan, I believe that differences about principle or substance give rise to most so-called personality clashes. It’s easy to dislike a person — and hard to disguise dislike — when that person reveals himself as incompetent, venal, manipulative, or corrupt. It seems to me that Caplan’s unfounded characterization of “most” disputes as personality clashes, and his back-handed dismissal of them as “battles of good versus evil,” reflects his own deep-seated taste for conflict avoidance, as an avowed and outspoken pacifist.

* * *

2. People’s moral objections to how other people use their own person and property often conflate innocent ignorance with willful vice.

I’ll have to compensate for Caplan’s vagueness by offering examples of what he might have in mind:

Al disapproves of Bob’s drunken driving, which caused a serious accident. Bob didn’t know he had been drinking vodka-spiked lemonade.

Bob was innocently ignorant of the vodka in the lemonade when he was drinking it. But Bob probably knew that he wasn’t fit to drive if he was impaired enough to have an alcohol-induced accident. It’s therefore reasonable to disapprove of Bob’s drunken driving, even though he didn’t intend to drink alcohol.

Jimmy and Johnny were playing with matches, and started a fire that caused their family’s house to burn to the ground. They escaped safely, but all of their family’s possessions — many of them irreplaceable — were lost. Nor did insurance cover the full cost of rebuilding their house.

Jimmy and Johnny may have been innocent, but it’s hard not to disapprove of their parents for lax child-rearing or imprudence (not keeping matches safely hidden from children).

Alison looked carefully before changing lanes, but a car on her right was in her blind spot. She almost hit the car as she began to change lanes, but pulled back into her own lane before hitting it. Jake, the driver of the other car, was enraged by the near collision and honked at Allison.

Jake was rightly enraged. He might have been killed. Alison may have looked carefully, but it’s evident that she didn’t look carefully enough.

LaShawn enjoys rap music, especially loud rap music. (Is there any other way to play it?) He has some neighbors who don’t enjoy rap music and don’t want to hear it. The only way to get LaShawn to turn down the volume is to complain to him about the music. It doesn’t occur to LaShawn that the volume is too high and that his neighbors might not care for rap music.

This used to be called “lack of consideration,” and it was rightly thought of as a willful vice.

DiDi is a cell-phone addict. She’s on the phone almost everywhere she goes, yakking it up with her friends. DiDi doesn’t seem to care that her overheard conversations — loud and one-sided — are annoying and distracting to many of the persons who are subjected to them.

Lack of consideration, again.

Jerry has a fondness for booze. But he stays sober until Friday night, when he goes to his local bar and gets plastered. The more he drinks the louder and more obnoxious he becomes.

When Jerry gets drunk, he isn’t in control of himself, in some psychological sense. Thus his behavior might be said, by some, to arise out of innocent ignorance. But Jerry is in control of himself before he gets drunk. He surely knows how he behaves when he’s drunk, and how his behavior affects others. Jerry’s drunken behavior arises from a willful vice.

Ted and Deirdre, a married couple, are highly paid yuppies. They worked hard to earn advanced degrees, and they work hard at their socially valued professions (physician and psychologist). They live in an upscale, gated community, drive $75,000 cars, dine at top-rated restaurants, etc. And yet, despite the obvious connection between their hard work and their incomes (and what those incomes afford them), they are ardent “liberals.” (See the sidebar for my views on modern “liberalism.”) They vote for left-wing candidates, and contribute as much as the law allows to the campaigns of left-wing candidates. They have many friends who are like them in background, accomplishments, and political views.

This may seem like a case of innocent ignorance, but it’s not. Ted and Deirdre (and their friends) are intelligent. They understand incentives. They understand (or they would, if they thought about it) that progressive taxation and regulations blunt incentives to work, save, and invest. They therefore understand (or could easily understand) that the plight of the poor and “downtrodden” who are supposed to be helped by progressive taxation and regulations is actually made worse by those things. They certainly understand such things viscerally because they make every effort to reduce their taxes (through legal means, of course); they do not contribute voluntarily to the U.S. Treasury (even though they know that they could); and they dislike regulations that affect them directly. Ted and Deidre (and the legions like them) allow their guilt-driven desire for “equality” to obscure easily grasped facts of life. They ignore or suppress the facts of life in order to preen as “caring” persons. At bottom, their ignorance is willful, and inexcusable in persons of intelligence.

In sum, it’s far from evident to me that “how other people use their own person[s] and property often conflate[s] innocent ignorance with willful vice.” There’s much less innocent ignorance in the world than Caplan would like to believe.

* * *

3. People’s best-founded moral objections to how other people use their own person and property are usually morally superfluous. Why? Because the Real World already provides ample punishment. Consider laziness. Even from a calm, detached point of view, a life of sloth seems morally objectionable. But there’s no need for you to berate the lazy – even inwardly. Life itself punishes laziness with poverty and unemployment… So even if you accept (as I do) the Rossian principle that a just world links virtue with pleasure and vice with pain, there is no need to add your harsh condemnation to balance the cosmic scales.

On what planet does Caplan live? Governments in the United States — the central government foremost among them — reward and encourage sloth through extended unemployment benefits, bogus disability payments, food stamps, etc., etc. etc. There’s every reason to voice one’s displeasure with such goings on, and to give force to that displeasure by working and voting against the policies and politicians who make it possible for the slothful to live on the earnings of others.

* * *

4. The “especially strangers” parenthetical preempts the strongest counter-examples to principled tolerance. There are obvious cases where you should strongly oppose what your spouse, children, or friends do with themselves or their stuff. But strangers? Not really.

Yes, really. See all of my comments above.

* * *

5. Intolerance is bad for the intolerant. As Buddha never said, “Holding onto anger is like drinking poison and expecting the other person to die.” The upshot is that the Real World punishes intolerance along with laziness, drunkenness, and gluttony. Perhaps this is the hidden wisdom of the truism that “Haters gonna hate.“

Here Caplan makes the mistake of identifying intolerance with anger. A person who is intolerant of carelessness, thoughtlessness, and willful vice isn’t angry all the time. He may be angered by careless, thoughtlessness, and willful vice when he sees them, but his anger is righteous, targeted, and controlled. Generally, he’s a happy person because he’s probably conservative.

It’s all well and good to tolerate freedom of choice and behavior, in the abstract. But civilization depends crucially on intolerance of particular choices and behaviors that result in real harm to others — psychic, material, and physical. Tolerance of such choices and behaviors is simply a kind of appeasement, which is what I would expect of Caplan — a man who can safely preach pacifism because he is well-guarded by the police and defense forces of his locality, State, and nation.

* * *

Related posts:

The Folly of Pacifism

The Folly of Pacifism, Again

More Pseudo-Libertarianism

Defending Liberty against (Pseudo) Libertarians

Not-So-Random Thoughts (XII)

Links to the other posts in this occasional series may be found at “Favorite Posts,” just below the list of topics.

* * *

“Intolerance as Illiberalism” by Kim R. Holmes (The Public Discourse, June 18, 2014) is yet another reminder, of innumerable reminders, that modern “liberalism” is a most intolerant creed. See my ironically titled “Tolerance on the Left” and its many links.

* * *

Speaking of intolerance, it’s hard to top a strident atheist like Richard Dawkins. See John Gray’s “The Closed Mind of Richard Dawkins” (The New Republic, October 2, 2014). Among the several posts in which I challenge the facile atheism of Dawkins and his ilk are “Further Thoughts about Metaphysical Cosmology” and “Scientism, Evolution, and the Meaning of Life.”

* * *

Some atheists — Dawkins among them — find a justification for their non-belief in evolution. On that topic, Gertrude Himmelfarb writes:

The fallacy in the ethics of evolution is the equation of the “struggle for existence” with the “survival of the fittest,” and the assumption that “the fittest” is identical with “the best.” But that struggle may favor the worst rather than the best. [“Evolution and Ethics, Revisited,” The New Atlantis, Spring 2014]

As I say in “Some Thoughts about Evolution,”

Survival and reproduction depend on many traits. A particular trait, considered in isolation, may seem to be helpful to the survival and reproduction of a group. But that trait may not be among the particular collection of traits that is most conducive to the group’s survival and reproduction. If that is the case, the trait will become less prevalent. Alternatively, if the trait is an essential member of the collection that is conducive to survival and reproduction, it will survive. But its survival depends on the other traits. The fact that X is a “good trait” does not, in itself, ensure the proliferation of X. And X will become less prevalent if other traits become more important to survival and reproduction.

The same goes for “bad” traits. Evolution is no guarantor of ethical goodness.

* * *

It shouldn’t be necessary to remind anyone that men and women are different. But it is. Lewis Wolpert gives it another try in “Yes, It’s Official, Men Are from Mars and Women from Venus, and Here’s the Science to Prove It” (The Telegraph, September 14, 2014). One of my posts on the subject is “The Harmful Myth of Inherent Equality.” I’m talking about general tendencies, of course, not iron-clad rules about “men’s roles” and “women’s roles.” Aside from procreation, I can’t readily name “roles” that fall exclusively to men or women out of biological necessity. There’s no biological reason, for example, that an especially strong and agile woman can’t be a combat soldier. But it is folly to lower the bar just so that more women can qualify as combat soldiers. The same goes for intellectual occupations. Women shouldn’t be discouraged from pursuing graduate degrees and professional careers in math, engineering, and the hard sciences, but the qualifications for entry and advancement in those fields shouldn’t be watered down just for the sake of increasing the representation of women.

* * *

Edward Feser, writing in “Nudge Nudge, Wink Wink” at his eponymous blog (October 24, 2014), notes

[Michael] Levin’s claim … that liberal policies cannot, given our cultural circumstances, be neutral concerning homosexuality. They will inevitably “send a message” of approval rather than mere neutrality or indifference.

Feser then quotes Levin:

[L]egislation “legalizing homosexuality” cannot be neutral because passing it would have an inexpungeable speech-act dimension. Society cannot grant unaccustomed rights and privileges to homosexuals while remaining neutral about the value of homosexuality.

Levin, who wrote that 30 years ago, gets a 10 out 10 for prescience. Just read “Abortion, ‘Gay Rights’, and Liberty” for a taste of the illiberalism that accompanies “liberal” causes like same-sex “marriage.”

* * *

“Liberalism” has evolved into hard-leftism. It’s main adherents are now an elite upper crust and their clients among the hoi polloi. Steve Sailer writes incisively about the socioeconomic divide in “A New Caste Society” (Taki’s Magazine, October 8, 2014). “‘Wading’ into Race, Culture, and IQ” offers a collection of links to related posts and articles.

* * *

One of the upper crust’s recent initiatives is so-called libertarian paternalism. Steven Teles skewers it thoroughly in “Nudge or Shove?” (The American Interest, December 10, 2014), a review of Cass Sunstein’s Why Nudge? The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism. I have written numerous times about Sunstein and (faux) libertarian paternalism. The most recent entry, “The Sunstein Effect Is Alive and Well in the White House,” ends with links to two dozen related posts. (See also Don Boudreaux, “Where Nudging Leads,” Cafe Hayek, January 24, 2015.)

* * *

Maria Konnikova gives some space to Jonathan Haidt in “Is Social Psychology Biased against Republicans?” (The New Yorker, October 30, 2014). It’s no secret that most academic disciplines other than math and the hard sciences are biased against Republicans, conservatives, libertarians, free markets, and liberty. I have something to say about it in “The Pseudo-Libertarian Temperament,” and in several of the posts listed here.

* * *

Keith E. Stanovich makes some good points about the limitations of intelligence in “Rational and Irrational Thought: The Thinking that IQ Tests Miss” (Scientific American, January 1, 2015). Stanovich writes:

The idea that IQ tests do not measure all the key human faculties is not new; critics of intelligence tests have been making that point for years. Robert J. Sternberg of Cornell University and Howard Gardner of Harvard talk about practical intelligence, creative intelligence, interpersonal intelligence, bodily-kinesthetic intelligence, and the like. Yet appending the word “intelligence” to all these other mental, physical and social entities promotes the very assumption the critics want to attack. If you inflate the concept of intelligence, you will inflate its close associates as well. And after 100 years of testing, it is a simple historical fact that the closest associate of the term “intelligence” is “the IQ test part of intelligence.”

I make a similar point in “Intelligence as a Dirty Word,” though I don’t denigrate IQ, which is a rather reliable predictor of performance in a broad range of endeavors.

* * *

Brian Caplan, whose pseudo-libertarianism rankles, tries to defend the concept of altruism in “The Evidence of Altruism” (EconLog, December 30, 2014). Caplan aids his case by using the loaded “selfishness” where he means “self-interest.” He also ignores empathy, which is a key ingredient of the Golden Rule. As for my view of altruism (as a concept), see “Egoism and Altruism.”

A Case for Redistribution, Not Made

Jessica Flanigan, one of the bleeders at Bleeding Heart Libertarians, offers this excuse for ripping money out of the hands of some persons and placing it into the hands of other persons:

Lately I’ve been thinking about my reasons for endorsing a UBI [universal basic income], especially given that I also share Michael Huemer’s skepticism about political authority. Consider this case:

- (1) Anne runs a business called PropertySystem, which manufacturers and maintains a private currency that can be traded for goods and services. The currency exists in users’ private accounts and Anne’s company provides security services for users. If someone tries to hack into the accounts she prevents them from doing so. The company also punishes users who violate the rules of PropertySystem. So if someone steals or tries to steal the currency from users, that person may have some of their currency taken away or they may even be held in one of PropertySystem’s jails. These services are financed through a yearly service fee.

This sounds fine. If everyone consented to join PropertySystem then they can’t really complain that Anne charges a fee for the services. There will be some questions about those who are not PropertySystem members, and how Anne’s company should treat them. But for the membership, consent seems to render what Anne is doing permissible. Next,

- (2) Anne thinks that it would be morally better if she gave money to poor people. She changes the user agreement for her currency holders to increase her maintenance fee and she gives some of the money to poor people. Or, Anne decides to just print more money and mail it to people so that she doesn’t have to raise fees, even though this could decrease the value of the holdings of her richest clients.

By changing the user agreement or distribution system in this way, Anne doesn’t seem to violate anyone’s rights. And PropertySystem does some good through its currency and protection services by using the company to benefit people who are badly off. Now imagine,

- (3) Anne decides that she doesn’t like PropertySystem competing with other providers so she compels everyone in a certain territory to use PropertySystem’s currency and protection services and to pay service fees, which she now calls taxes.

…[T[here are moral reasons in favor of Anne’s policy changes from (1) to (2). She changed the property conventions in ways that did not violate anyone’s pre-political ownership rights while still benefiting the badly off. If Anne implemented policy (2) after she started forcing everyone to join her company (3) it would still be morally better than policy (1) despite the fact that (3) is unjust.This is the reason I favor a basic income. Such a policy balances the reasonable complaints that people may have about the effects of a property system that they never consented to join. Though redistribution cannot justify forcing everyone to join a property system, it can at least compensate people who are very badly off partly because they were forced to join that property system. Some people will do very well under a property system that nevertheless violates their rights. But it is not a further rights violation if a property system doesn’t benefit the rich as much as it possibly could.

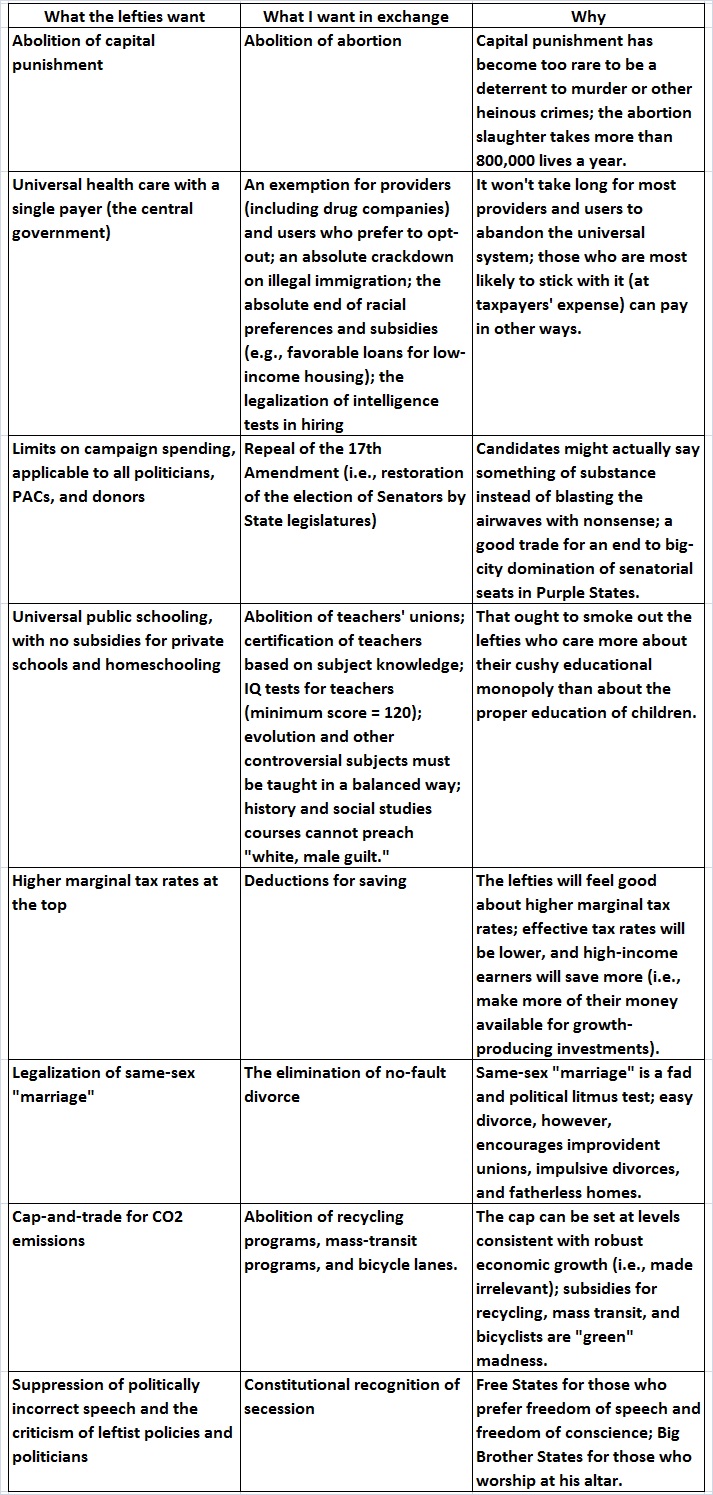

Let’s Make a Deal

The last deal negates all of the concessions made in the other deals — for those of us who will choose to live in Free States.

Has America Always Been Leftist?

Dr. John J. Ray, writing at Dissecting Leftism, enraged some Americans with two recent posts about America and leftism. I’m grateful to Dr. Ray for publishing, in a subsequent post, a message that I sent to him about the two posts in question. Herein, I elaborate on the points that I made in my message to Dr. Ray.

In “America Has Always Been Leftist,” Dr. Ray asserts the following:

As most Americans learn around the time of Thanksgiving, America was founded by fanatical communists. They forbad [sic] private ownership of land and insisted that all produce be shared communally. If that’s not communism, nothing is. They were such fanatics that a third of them had to starve to death before they decided that communism wasn’t such a good idea and went back to the way things had always been done in stodgy old England.

So what should we expect of a nation dominated by the descendants of fanatical communists? What we should expect is exactly what we actually got, I submit.

But before I get to that, let me ensure complete clarity about what the core of Leftism is. The content of Leftism changes from time to time. Before WWII, Leftists world wide were energetic champions of eugenics, for instance. Leftists now abhor it. So what is constant in Leftism? Anger. Leftists in all eras are so dissatisfied with the society in which they live that they want sweeping changes to it. And they thirst for power to achieve that. That is Leftism.

Pace Dr. Ray, it is well known that the “fanatical communists” of Plymouth Colony quickly abandoned their experiment in communism; for example, Jerry Bowyer writes:

…America was founded by socialists who had the humility to learn from their initial mistakes and embrace freedom.

One of the earliest and arguably most historically significant North American colonies was Plymouth Colony, founded in 1620 in what is now known as Plymouth, Massachusetts. As I’ve outlined in greater detail here before (Lessons From a Capitalist Thanksgiving), the original colony had written into its charter a system of communal property and labor.

As William Bradford recorded in his Of Plymouth Plantation, a people who had formerly been known for their virtue and hard work became lazy and unproductive. Resources were squandered, vegetables were allowed to rot on the ground and mass starvation was the result. And where there is starvation, there is plague. After 2 1/2 years, the leaders of the colony decided to abandon their socialist mandate and create a system which honored private property. The colony survived and thrived and the abundance which resulted was what was celebrated at that iconic Thanksgiving feast….

It is, moreover, an exaggeration to say that America is “a nation dominated by the descendants of fanatical communists.” First, as I’ve just pointed out, the inhabitants of Plymouth Colony were hardly fanatical. If they had been, they would have chosen the sure impoverishment (and probable death) of communism over the relative prosperity (and liberty) that came their way when they abandoned their infatuation with communism.

Second, only a small minority of today’s Americans — even of today’s white Americans — can count themselves as “full blooded” descendants of the inhabitants of Plymouth Colony or other early settlers might also have harbored socialistic delusions. There have been too many immigrants from continental Europe and too much “miscegenation” for that to be true.

Third, and fundamentally, it is meaningless to generalize about “Americans,” as I’ve explained at length here. There are and have been individual Americans of many political persuasions, most of them confused and contradictory.

That said, I do agree, generally, with Dr. Ray’s characterization of the motivations underlying the War of Independence. In his next post, “Has America Always Been Leftist?,” Dr. Ray says this:

I did learn something very important from [the critics of “America Has Always Been Leftist”]. It was vividly brought home to me how impressive fine words are to most people. When even patriotic American conservatives can be taken in by them, it shows why Leftists have so much influence. Leftists are nothing but fine words. To me fine words are only provisionally important. They have to be backed up by deeds and it is the deeds that matter.

An excellent example of how fine words impress even conservatives is the preamble to the Declaration of Independence. It is full of fine words and noble sentiments. Most political documents are. Stalin’s Soviet constitution also was a high-minded document proclaiming all sorts of rights for Soviet citizens — rights which were denied in fact.

So once you look past the grand generalizations of the Declaration’s introduction and get to the nitty gritty of what the Yankee grandees really wanted fixed, you see that it is very mundane, if not ignoble. What was really bothering them was restrictions on their powers to legislate. They wanted more laws, not less! Very Leftist.

And from THAT starting point you can see why the war was fought and for whose benefit. The grandees concerned had a lot of influence and were good at fine talk so they could muster an army — and they did. And who benefited from the war? Was it the poor farmers and tradesmen who died as foot-soldiers in it? No way! It was the grandees who started the war. They emerged with exactly what they wanted: More power.

I am sorry if that account sounds offensive to people who still believe the original propaganda, but if you ignore the fancy talk and just look at the facts, that is what happened.

Dr. Ray’s sweeping use of “Leftist” aside, his main point is well taken. I made a similar observation in response to a post by Timothy Sandefur, who was then guest-blogging at The Volokh Conspiracy. Sandefur, writing about his book The Conscience of the Constitution, asserted that “The American founders held that people are inherently free—that is, no person has a basic entitlement to dictate how other people may lead their lives.” I responded:

Did they, really? All of them, including the slave owners? Or did they simply want to relocate the seat of power from London to the various State capitals, where local preferences (including anti-libertarian ones) could prevail? Wasn’t that what the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation were all about? The Constitution simply moved some of the power toward the national capital, mainly for the conduct of foreign policy and trade. Despite that, the Constitution was a “States’ rights” document, and remained that way until the ratification of Amendment XIV, from which much anti-libertarian mischief has emanated.

In response to Sandefur’s next post, I wrote:

Why can’t you [Sandefur] just admit that the Declaration of Independence was a p.r. piece, penned (in the main) by a slave-owner and subscribed to by various and sundry elites who (understandably) resented their treatment at the hands of a far-away sovereign and Parliament? You’re trying to make more of the Declaration — laudable as its sentiments are — than should be made of it….

In sum, the War of Independence isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be.

And there’s no doubt that liberty suffered in the long run as a result of the North’s victory in the Civil War. I return to Dr. Ray’s “America Has Always Been Leftist,” where he says this:

“Only” half a million men died [in the Civil War]. And for what? EVERY other country on earth abolished slavery without the need for a war. Does that not tell us something? It should. In his famous letter to Horace Greeley [link added], Lincoln himself admitted that slavery was not the main issue. The issue was the dominance of central government. V.I. Lenin call your office. Lincoln didn’t call it “dominance of central government”, of course. He called it “the union” but the result is the same.

And just about everything Lincoln did was without a shred of constitional justification and in fact breached the constitution. Hitler at least had the grace to get an “enabling act” passed by the German parliament. Lincoln just marched on regardless. He destroyed the liberty of the press (there goes your first amendment) and locked up thousands of war opponents (there goes your 4th amendment). But most centrally, Lincoln’s whole enterprise was a defiance of the basic American constitutional dispensation that the states are sovereign, not the federal government. Lincoln turned that on its head. The feds now became the main source of power and authority. There is no doubt that Lincoln talked a good talk. He even used to persuade me once. But his deeds reek of Fascism.

A good example of the large gap between his deeds and words is that masterpiece of propaganda, the Gettysburg address. Goebbels admired it for good reason. In case anybody hasn’t noticed, Lincoln claimed that his war was to ensure “government of the people, by the people, for the people” — which was exactly what he had just denied to the South! Only Yankees are people, apparently. Hitler thought certain groups weren’t people too.

Overwrought? Perhaps, but if Lincoln wasn’t a left-statist, he at least set an example for extra-constitutional activism that inspired Theodore Roosevelt’s hyper-activism (e.g., see this and this). TR, of course, set an example that was followed and enlarged upon by most of his successors, unto the present day.

Another anti-libertarian legacy of the Civil War is the false belief that it “proved” the unconstitutionality of secession. Balderdash! Secession is legal, Justice Scalia’s dictum to the contrary notwithstanding. (See this, this, and this, for example.) And the ever-present threat of secession might have helped to keep the central government from overstepping its constitutional bounds.

I must conclude, however, that the American Revolution and Civil War have little to do with “left” (or “right”) and much to do with human venality and power-lust, which are found in persons of all political persuasions.

The genius of the Constitution was that it provided mechanisms for curbing the anti-libertarian effects of venality and power-lust. The tragedy of the Constitution is that those mechanisms have been destroyed. If Dr. Ray were to say that Americans have gradually lost their liberty through successive and cumulative violations of the Constitution, I would agree with him

And if Dr. Ray were to say that Americans have become the captives of a leftist state, and are likely to remain so, I would agree with him.

* * *

Related posts:

FDR and Fascism

The Modern Presidency: A Tour of American History

An FDR Reader

The People’s Romance

Secession

The Near-Victory of Communism

A Declaration of Independence

Tocqueville’s Prescience

Invoking Hitler

The Left

The Constitution: Original Meaning, Corruption, and Restoration

I Want My Country Back

Our Enemy, the State

The Left’s Agenda

The Meaning of Liberty

The Southern Secession Reconsidered

The Left and Its Delusions

Burkean Libertarianism

A Declaration and Defense of My Prejudices about Governance

Society and the State

Why Conservatism Works

Liberty and Society

Tolerance on the Left

The Eclipse of “Old America”

A Contrarian View of Universal Suffrage

Defending Liberty against (Pseudo) Libertarians

Defining Liberty

Conservatism as Right-Minarchism

“We the People” and Big Government

Parsing Political Philosophy (II)

How Libertarians Ought to Think about the Constitution

Romanticizing the State

Libertarianism and the State

Libertarianism and the State

The version of libertarianism that I address here is minarchism: the belief that the state — whether necessary or inevitable — is legitimate only if its functions are limited to the defense of its citizens from foreign and domestic predators. Anarchism — an extreme form of libertarianism — is a pipe dream, for reasons I detail in several posts; e.g., here.

Under minarchism, the order that is necessary to liberty — peaceful, willing coexistence and its concomitant: beneficially cooperative behavior — is fostered by the institutions of civil society: family, church, club, and the like. Those institutions inculcate morality and enforce it through “social pressure.” The state (ideally) deals only with those persons who violate fundamental canons of behavior toward other persons (e.g., the last six of the Ten Commandments), and also defends the populace from foreign enemies.

Though America is a long way from minarchism, something like it was possible under the Articles of Confederation and in the early decades under the Constitution, when the central government was relatively unobtrusive and most legal constraints on human action were levied by State and local governments. In those conditions, Americans could rid themselves of unwanted social and legal strictures by leaving one State for another or venturing into the relatively ungoverned frontier territories.

Having defined libertarianism (for the purpose of this post), I will now state the surprising conclusion to which I have come: Its adherents are unwitting statists.