Philosophical musings by a non-philosopher which are meant to be accessible to other non-philosophers.

Ontology is the branch of philosophy that deals with existence. Epistemology is the branch of philosophy that deals with knowledge.

I submit (with no claim to originality) that existence (what really is) is independent of knowledge (proposition A), but knowledge is impossible without existence (proposition B).

In proposition A, I include in existence those things that exist in the present, those things that have existed in the past, and the processes (happenings) by which past existences either end (e.g., death of an organism, collapse of a star) or become present existences (e.g., an older version of a living person, the formation of a new star). That which exists is real; existence is reality.

In proposition B, I mean knowledge as knowledge of that which exists, and not the kind of “knowledge” that arises from misperception, hallucination, erroneous deduction, lying, and so on. Much of what is called scientific knowledge is “knowledge” of the latter kind because, as scientists know (when they aren’t advocates) scientific knowledge is provisional. Proposition B implies that knowledge is something that human beings and other living organisms possess, to widely varying degrees of complexity. (A flower may “know” that the Sun is in a certain direction, but not in the same way that a human being knows it.) In what follows, I assume the perspective of human beings, including various compilations of knowledge resulting from human endeavors. (Aside: Knowledge is self-referential, in that it exists and is known to exist.)

An example of proposition A is the claim that there is a falling tree (it exists), even if no one sees, hears, or otherwise detects the tree falling. An example of proposition B is the converse of Cogito, ergo sum, I think, therefore I am; namely, I am, therefore I (a sentient being) am able to know that I am (exist).

Here’s a simple illustration of proposition A. You have a coin in your pocket, though I can’t see it. The coin is, and its existence in your pocket doesn’t depend on my act of observing it. You may not even know that there is a coin in your pocket. But it exists — it is — as you will discover later when you empty your pocket.

Here’s another one. Earth spins on its axis, even though the “average” person perceives it only indirectly in the daytime (by the apparent movement of the Sun) and has no easy way of perceiving it (without the aid of a Foucault pendulum) when it is dark or when asleep. Sunrise (or at least a diminution of darkness) is a simple bit of evidence for the reality of Earth spinning on its axis without our having perceived it.

Now for a somewhat more sophisticated illustration of proposition A. One interpretation of quantum mechanics is that a sub-atomic particle (really an electromagnetic phenomenon) exists in an indeterminate state until an observer measures it, at which time its state is determinate. There’s no question that the particle exists independently of observation (knowledge of the particle’s existence), but its specific characteristic (quantum state) is determined by the act of observation. Does this mean that existence of a specific kind depends on knowledge? No. It means that observation determines the state of the particle, which can then be known. Observation precedes knowledge, even if the gap is only infinitesimal. (A clear-cut case is the autopsy of a dead person to determine his cause of death. The autopsy didn’t cause the person’s death, but came after it as an act of observation.)

Regarding proposition B, there are known knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns, and unknown “knowns”. Examples:

Known knowns (real knowledge = true statements about existence) — The experiences of a conscious, sane, and honest person: I exist; am eating; I had a dream last night; etc. (Recollections of details and events, however, are often mistaken, especially with the passage of time.)

Known unknowns (provisional statements of fact; things that must be or have been but which are not in evidence) — Scientific theories, hypotheses, data upon which these are based, and conclusions drawn from them. The immediate causes of the deaths of most persons who have died since the advent of homo sapiens. The material process by which the universe came to be (i.e., what happened to cause the Big Bang, if there was a Big Bang).

Unknown unknowns (things that exist but are unknown to anyone) — Almost everything about the universe.

Unknown “knowns” (delusions and outright falsehoods accepted by some persons as facts) — Frauds, scientific and other. The apparent reality of a dream.

Regarding unknown “knowns”, one might dream of conversing with a dead person, for example. The conversation isn’t real, only the dream is. And it is real only to the dreamer. But it is real, nevertheless. And the brain activity that causes a dream is real even if the person in whom the activity occurs has no perception or memory of a dream. A dream is analogous to a movie about fictional characters. The movie is real but the fictional characters exist only in the script of the movie and the movie itself. The actors who play the fictional characters are themselves, not the fictional characters.

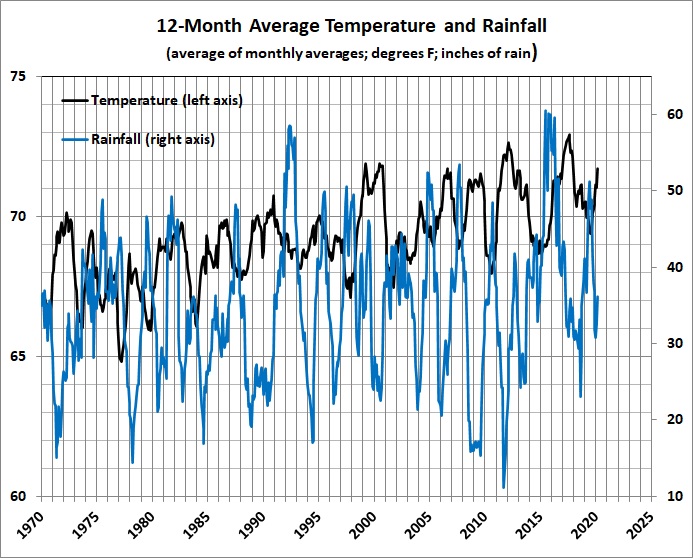

There is a fine line between known unknowns (provisional statements of fact) and unknown “knowns” (delusions and outright falsehoods). The former are statements about existence that are made in good faith. The latter are self-delusions of some kind (e.g., the apparent reality of a dream as it occurs), falsehoods that acquire the status of “truth” (e.g., George Washington’s false teeth were made of wood), or statements of “fact” that are made in bad faith (e.g., adjusting the historic temperature record to make the recent past seem warmer relative to the more distant past).

The moral of the story is that a doubting Thomas is a wise person.