Utilitarianism is an empty concept. And it is inimical to liberty.

What is utilitarianism, as I use the term? This:

1. (Philosophy) the doctrine that the morally correct course of action consists in the greatest good for the greatest number, that is, in maximizing the total benefit resulting, without regard to the distribution of benefits and burdens

To maximize the total benefit is to maximize social welfare, which is the well-being of all persons, somehow measured and aggregated. A true social-welfare maximizer would strive to maximize the social welfare of the planet. But schemes to maximize social welfare usually are aimed at maximizing it for the persons in a particular country, so they really are schemes to maximize national welfare.

National welfare may conflict with planetary welfare; the former may be increased (by some arbitrary measure) at the expense of the latter. Suppose, for example, that Great Britain had won the Revolutionary War and forced Americans to live on starvation wages while making things for the enjoyment of the British people. A lot of Britons would have been better off materially (though perhaps not spiritually), while most Americans certainly would have been worse off. The national welfare of Great Britain would have been improved, if not maximized, “without regard to the distribution of benefits and burdens.” On a contemporary note, anti-globalists assert (wrongly) that globalization of commerce exploits the people of poor countries. If they were right, they would at least have the distinction of striving to maximize planetary welfare. (Though there is no such thing, as I will show.)

THE UTILITARIAN WORLD VIEW

A utilitarian will favor a certain policy if a comparison of its costs and benefits shows that the benefits exceed the costs — even though the persons bearing the costs are often not the persons who accrue the benefits. That is to say, utilitarianism authorizes the redistribution of income and wealth for the “greater good”. Thus the many governmental schemes that are redistributive by design, for example, the “progressive” income tax (i.e., the taxation of income at graduated rates), Social Security (which yields greater “returns” to low-income workers than to high-income workers, and which taxes current workers for the benefit of retirees), and Medicaid (which is mainly for the benefit of persons whose tax burden is low or nil).

One utilitarian justification of such schemes is the fallacious and short-sighted assertion that persons with higher incomes gain less “utility” as their incomes rise, whereas the persons to whom that income is transferred gain much more “utility” because their incomes are lower. This principle is sometimes stated as “a dollar means more to a poor man than to a rich one”.

That is so because utilitarians are accountants of the soul, who believe (implicitly, at least) that it is within their power to balance the unhappiness of those who bear costs against the happiness of those who accrue benefits. The precise formulation, according to John Stuart Mill, is “the greatest amount of happiness altogether” (Utilitarianism, Chapter II, Section 16.)

UTILITARIANISM AS ECONOMIC FALLACY, ARROGANCE, AND HYPOCRISY

It follows — if you accept the assumption of diminishing marginal utility and ignore the negative effect of redistribution on economic growth — that overall utility (a.k.a. the social welfare function) will be raised if income is redistributed from high-income earners to low-income earners, and if wealth is redistributed from the wealthier to the less wealthy. But in order to know when to stop redistributing income or wealth, you must be able to measure the utility of individuals with some precision, and you must be able to sum those individual views of utility across the entire nation. Nay, across the entire world, if you truly want to maximize social welfare.

Most leftists (and not a few economists) don’t rely on the assumption of diminishing marginal utility as a basis for redistributing income and wealth. To them, it’s just a matter of “fairness” or “social justice”. It’s odd, though, that affluent leftists seem unable to support redistributive schemes that would reduce their income and wealth to, say, the global median for each measure. “Fairness” and “social justice” are all right in their place — in lecture halls and op-ed columns — but the affluent leftist will keep them at a comfortable distance from his luxurious abode.

In any event, leftists (including some masquerading as economists) who deign to offer an economic justification for redistribution usually fall back on the assumption of the diminishing marginal utility (DMU) of income and wealth. In doing so, they commit (at least) four errors.

The first error is the fallacy of misplaced concreteness which is found in the notion of utility. Have you ever been able to measure your own state of happiness? I mean measure it, not just say that you’re feeling happier today than you were when your pet dog died. It’s an impossible task, isn’t it? If you can’t measure your own happiness, how can you (or anyone) presume to measure — and aggregate — the happiness of millions or billions of individual human beings? It can’t be done.

Which brings me to the second error, which is an error of arrogance. Given the impossibility of measuring one person’s happiness, and the consequent impossibility of measuring and comparing the happiness of many persons, it is pure arrogance to insist that “society” would be better off if X amount of income or wealth were transferred from Group A to Group B.

Think of it this way: A tax levied on Group A for the benefit of Group B doesn’t make Group A better off. It may make some smug members of Group A feel superior to other members of Group A, but it doesn’t make all members of Group A better off. In fact, most members of Group A are likely to feel worse off. It takes an arrogant so-and-so to insist that “society” is somehow better off even though a lot of persons (i.e., members of “society”) have been made worse off.

The third error lies in the implicit assumption embedded in the idea of DMU. The assumption is that as one’s income or wealth rises one continues to consume the same goods and services, but more of them. Thus the example of chocolate cake: The first slice is enjoyed heartily, the second slice is enjoyed but less heartily, the third slice is consumed reluctantly, and the fourth slice is rejected.

But that’s a bad example. The fact is that having more income or wealth enables a person to consume goods and services of greater variety and higher quality. Given that, it is possible to increase one’s utility by shifting from a “third helping” of a cheap product to a “first helping” of an expensive one, and to keep on doing so as one’s income rises. Perhaps without limit, given the profusion of goods and services available to consumers.

And if should you run out of new and different things to buy (an unlikely event), you can make yourself happier by acquiring more income to amass more wealth, and (if it makes you happy) by giving away some of your wealth. How much happier? Well, if you’re a “scorekeeper” (as very wealthy persons seem to be), your happiness rises immeasurably when your wealth rises from, say, $10 million to $100 million to $1 billion — and if your wealth-based income rises proportionally. How much happier is “immeasurably happier”? Who knows? That’s why I say “immeasurably” — there’s no way of telling. Which is why it’s arrogant to say that a wealthy person doesn’t “need” his next $1 million or $10 million, or that they don’t give him as much happiness as the preceding $1 million or $10 million.

All of that notwithstanding, the committed believer in DMU will shrug and say that at some point DMU must set in. Which leads me to the fourth error, which is introspective failure. If you’re like most mere mortals (as I am), your income during your early working years barely covered your bills. If you’re more than a few years into your working career, subsequent pay raises probably made you feel better about your financial state — not just a bit better but a whole lot better. Those raises enabled you to enjoy newer, better things (as discussed above). And if your real income has risen by a factor of two or three or more — and if you haven’t messed up your personal life (which is another matter) — you’re probably incalculably happier than when you were just able to pay your bills. And you’re especially happy if you put aside a good chunk of money for your retirement, the anticipation and enjoyment of which adds a degree of utility (such a prosaic word) that was probably beyond imagining when you were in your twenties, thirties, and forties.

In sum, the idea that one’s marginal utility (an unmeasurable abstraction) diminishes with one’s income or wealth is nothing more than an assumption that simply doesn’t square with my experience. And I’m sure that my experience is far from unique, though I’m not arrogant enough to believe that it’s universal.

UTILITARIANISM VS. LIBERTY

I have defined liberty as

the general observance of social norms that enables a people to enjoy…peaceful, willing coexistence and its concomitant: beneficially cooperative behavior.

Where do social norms come into it? The observance of social norms — society’s customs and morals — creates mutual trust, respect, and forbearance, from which flow peaceful, willing coexistence and beneficially cooperative behavior. In such conditions, only a minimal state is required to deal with those who will not live in peaceful coexistence, that is, foreign and domestic aggressors. And prosperity flows from cooperative economic behavior — the exchange of goods and services for the mutual benefit of the parties who to the exchange.

Society isn’t to be confused with nation or any other kind of geopolitical entity. Society — true society — is

3a : an enduring and cooperating social group whose members have developed organized patterns of relationships through interaction with one another.

A close-knit group, in other words. It should go without saying that the members of such a group will be bound by culture: language, customs, morals, and (usually) religion. Their observance of a common set of social norms enables them to enjoy peaceful, willing coexistence and beneficially cooperative behavior.

Free markets mimic some aspects of society, in that they are physical and virtual places where buyers and sellers meet peacefully (almost all of the time) and willingly, to cooperate for their mutual benefit. Free markets thus transcend (or can transcend) the cultural differences that delineate societies.

Large geopolitical areas also mimic some aspects of society, in that their residents meet peacefully (most of the time). But when “cooperation” in such matters as mutual aid (care for the elderly, disaster recovery, etc.) is forced by government; it isn’t true cooperation, which is voluntary.

In any event, the United States is not a society. Even aside from the growing black-white divide, the bonds of nationhood are far weaker than those of a true society (or a free market), and are therefore easier to subvert. Even persons of the left agree that mutual trust, respect, and forbearance are at a low ebb — probably their lowest ebb since the Civil War.

Therein lies a clue to the emptiness of utilitarianism. Why should a qualified white person care about or believe in the national welfare when, in furtherance of national welfare (or something), a job or university slot for which the white person applies is given, instead, to a less qualified black person because of racial quotas that are imposed or authorized by government? Why should a taxpayer care about or believe in the national welfare if he is forced by government to share the burden of enlarging it through government-enforced transfer payments to those who don’t pay taxes? By what right or gift of omniscience is a social engineer able to intuit the feelings of 300-plus million individual persons and adjudge that the national welfare will be maximized if some persons are forced to cede privileges or money to other persons?

Consider Robin Hanson’s utilitarian scheme, which he calls futarchy:

In futarchy, democracy would continue to say what we want, but betting markets would now say how to get it. That is, elected representatives would formally define and manage an after-the-fact measurement of national welfare, while market speculators would say which policies they expect to raise national welfare….

Futarchy is intended to be ideologically neutral; it could result in anything from an extreme socialism to an extreme minarchy, depending on what voters say they want, and on what speculators think would get it for them….

A betting market can estimate whether a proposed policy would increase national welfare by comparing two conditional estimates: national welfare conditional on adopting the proposed policy, and national welfare conditional on not adopting the proposed policy.

Get it? “Democracy would say what we want” and futarchy “could result in anything from an extreme socialism to an extreme minarchy, depending on what voters say they want.” Hanson the social engineer believes that the “values” to be maximized should be determined “democratically,” that is, by majorities (however slim) of voters. Further, it’s all right with Hanson if those majorities lead to socialism. So Hanson envisions national welfare that isn’t really national; it’s determined by what’s approved by one-half-plus-one of the persons who vote. Scratch that. It’s determined by the politicians who are elected by as few as one-half-plus-one of the persons who vote, and in turn by unelected bureaucrats and judges — many of whom were appointed by politicians long out of office. It is those unelected relics of barely elected politicians who really establish most of the rules that govern much of Americans’ economic and social behavior.

Hanson’s version of national welfare amounts to this: whatever is is right. If Hitler had been elected by a slim majority of Germans, thereby legitimating him in Hanson’s view, his directives would have expressed the national will of Germans and, to the extent that they were carried out, would have maximized the national welfare of Germany.

Hanson’s futarchy is so bizarre as to be laughable. Ralph Merkle nevertheless takes the ball from Hanson and runs with it:

We choose to be more specific [than Hanson] about the definition of what we shall call the “collective welfare”, for the very simple reason that “voting on values” retains the dubious voting mechanism as a core component of futarchy….

We can create a DAO Democracy capable of self-improvement which has unlimited growth potential by modifying futarchy to use an unmodifiable democratic collective welfare metric, adapting it to work as a Decentralized Autonomous Organization, implementing an initial system using simple components (these components including the democratic collective welfare metric, a mechanism for adopting legislation (bills)) and using a built-in prediction market to filter through and adopt proposals for improved components….

1) Anyone can propose a bill at any time….

8) Any existing law can be amended or repealed with the same ease with which a new law can be proposed….

13) The only time this governance process would support “the tyranny of the majority” would be if oppression of some minority actually made the majority better off, and the majority was made sufficiently better off that it outweighed the resulting misery to the minority.

So, for example, we should trust that the super-majority of voters whose incomes are below the national median wouldn’t further tax the voters whose incomes are above the national median? And we should assume that the below-median voters would eventually notice that the heavy-taxation policy is causing their real incomes to decline? And we should assume that those below-median voters would care in any event, given the psychic income they derive from sticking it to “the rich”? What a fairy tale. The next thing I would expect Merkle to assert is that the gentile majority of Germans didn’t applaud or condone the oppression of the Jewish minority, that Muslim hordes that surround Israel aren’t scheming to annihilate it, and on into the fantasy-filled night.

How many times must I say it? There is no such thing as a national, social, cosmic, global, or aggregate welfare function of any kind. (Go here for a long but probably not exhaustive list of related posts.)

To show why there’s no such thing as an aggregate welfare function, I usually resort to a homely example:

- A dislikes B and punches B in the nose.

- A is happier; B is unhappier.

- Someone (call him Omniscient Social Engineer) somehow measures A’s gain in happiness, compares it with B’s loss of happiness, and declares that the former outweighs the latter. Thus it is a socially beneficial thing if A punches B in the nose, or the government takes money from B and gives it to A, or the government forces employers to hire people who look like A at the expense of people who look like B, etc.

If you’re a B — and there are a lot of them out there — do you believe that A’s gain somehow offsets your loss? Unless you’re a masochist or a victim of the Stockholm syndrome, you’ll be ticked off about what A has done to you, or government has done to you on A’s behalf. Who is an Omniscient Social Engineer — a Hanson or Merkle — to say that your loss is offset by A’s gain? That’s just pseudo-scientific hogwash, also known as utilitarianism. But that’s exactly what Hanson, Merkle, etc., are peddling when they invoke social welfare, national welfare, planetary welfare, or any other aggregate measure of welfare.

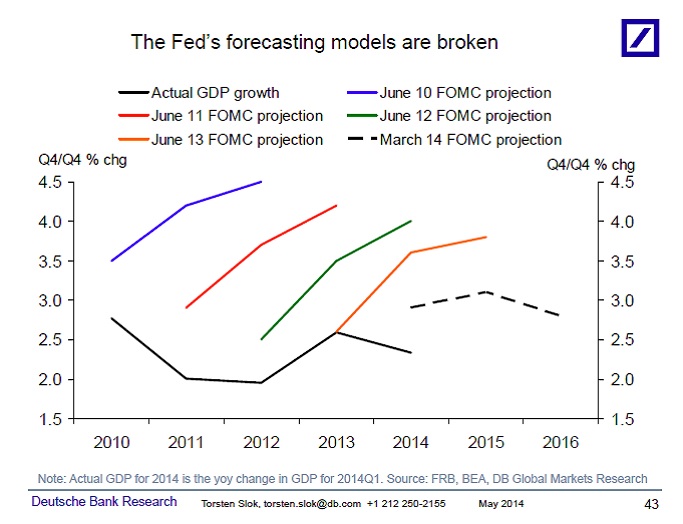

What about GDP as a measure of national welfare? Even economists — or most of them — admit that GDP doesn’t measure aggregate happiness, well-being, or any similar thing. To begin with, a lot of stuff is omitted from GDP, including so-called household production, which is the effort (not to mention love) that Moms (it’s usually Moms) put into the care, feeding, and hugging of their families. And for reasons hinted at in the preceding paragraph, the income that’s earned by A, B, C, etc., not only buys different things, but A, B, C, etc., place unique (and changing) values on those different things and derive different and unmeasurable degrees of happiness (and sometimes remorse) from them.

If GDP, which is is relatively easy to estimate (within a broad range of error), doesn’t measure national welfare, what could? Certainly not systems of the kind proposed by Hanson or Merkle, both of which pretend to aggregate that which can’t be aggregated: the happiness of an entire population. (Try it with one stranger, and see if you can arrive at a joint measure of happiness.)

The worst thing about utilitarian schemes and their real-world counterparts (regulation, progressive taxation, affirmative action, etc.) is that they are anti-libertarian. As I say here,

utilitarianism compromises liberty because it accords no value to individual decisions about preferred courses of action. Decisions, to a utilitarian, are valid only if they comply with the views of the utilitarian, who feigns omniscience about the (incommensurable) happiness of individuals.

No system can be better than the “system” of liberty, in which a minimal government protects its citizens from each other and from foreign enemies — and nothing else. Liberty was lost in the instant that government was empowered not only to protect A from B (and vice versa) but to inflict A’s preferences on B (and vice versa).

Futarchy — and every other utilitarian scheme — exhibits total disregard for liberty, and for the social norms on which it ultimately depends. That’s no surprise. Social or national welfare is obviously more important to utilitarians than liberty. If half of all Americans (or American voters) want something, all of us should have it, by God, even if “it” is virtual enslavement by the regulatory-welfare state, a declining rate of economic growth, and fewer jobs for young black men, who then take it out on each other, their neighbors, and random whites.

Patrick Henry didn’t say “Give me maximum national welfare or give me death,” he said “Give me liberty or give me death.” Liberty enables people to make their own choices about what’s best for them. And if they make bad choices, they can learn from them and go on to make better ones.

No better “system” has been invented or will ever be invented. Those who second-guess liberty — utilitarians, reformers, activists, social justice warriors, and all the rest — only undermine it. And in doing so, they most assuredly diminish the welfare of most people just to advance their own smug view of how the world should be arranged.

UTILITARIANISM AND GUN CONTROL VS. LIBERTY

Gun control has been much in the news in recent years and decades. The real problem isn’t guns, but morality, as discussed here. But arguments for gun control are utilitarian, and gun control is a serious threat to liberty.

Consider the relationship between guns and crime. Here is John Lott’s controversial finding (as summarized at Wikipedia several years ago):

[A]llowing adults to carry concealed weapons significantly reduces crime in America. [Lott] supports this position by an exhaustive tabulation of various social and economic data from census and other population surveys of individual United States counties in different years, which he fits into a large multifactorial mathematical model of crime rate. His published results generally show a reduction in violent crime associated with the adoption by states of laws allowing the general adult population to freely carry concealed weapons.

Suppose Lott is right. (There is good evidence that he isn’t wrong. RAND’s recent meta-study is laughably subjective.)

If more concealed weapons lead to less crime, then the proper utilitarian policy is for governments to be more lenient about owning and bearing firearms. A policy of leniency would also be consistent with two tenets of libertarian-conservatism:

- the right of self-defense

- taking responsibility for one’s own safety beyond that provided by guardians (be they family, friends, passing strangers, or minions of the state), because guardians can’t be everywhere, all the time, and aren’t always effective when they are present.

Only a foolish, extreme pacifist denies the first tenet. No one (but the same foolish pacifist) can deny the second tenet in good faith.

However, if Lott is right and government policy were to veer toward greater leniency, it is possible that more innocent persons will be killed by firearms than would otherwise be the case. The incidence of accidental shootings could rise, even as the rate of crime drops.

Which is worse, more crime or more accidental shootings? Not even a utilitarian can say, because no formula can objectively weigh the two things. (Not that that will stop a utilitarian from making up some weights, to arrive at a formula that supports his prejudice in the matter.) Both have psychological aspects (victimization, wound, grief) that defy quantification. The only reasonable way out of the dilemma is to favor liberty and punish wrong-doing where it occurs. The alternative — more restrictions on gun ownership — punishes many (those who would defend themselves), instead of punishing actual wrong-doers.

Suppose Lott is wrong, and more guns mean more crime. Would that militate against the right to own and bear arms? Only if utilitarianism is allowed to override liberty. Again, I would favor liberty, and punish wrong-doing where it occurs, instead of preventing some persons from defending themselves.

In sum, the ownership and carrying of guns isn’t a problem that’s amenable to a utilitarian solution. (Few problems are, and none of them involves government.) The ownership and carrying of guns is an emotional issue (and not only on the part of gun-grabbers). The natural reaction to highly publicized mass-shootings is to “do something”.

In fact, the “something” isn’t within the power of government to do, unless it undoes many policies that have subverted civil society over the past several decades. Mass shootings — and mass killings, in general — arise from social decay. Mass killings will not stop, or slow to a trickle, until the social decay stops and is reversed — which may be never.

So when the next restriction on guns fails to stop mass murder, the next restriction on guns (or explosives, etc.) will be adopted in an effort to stop it. And so on until self-defense, personal responsibility — and liberty — are fainter memories than they already are.

My point is that it doesn’t matter whether Lott is right or wrong. Utilitarianism has no place in it for liberty. My right to self-defense and my willingness to take personal responsibility for it — given the likelihood that government will fail to defend me — shouldn’t be compromised by hysterical responses to notorious cases of mass murder. The underlying aim of the hysterics (and the left-wingers who encourage them) is the disarming of the populace. The necessary result will be the disarming of law-abiding citizens, so that they become easier prey for criminals and psychopaths.

A proper libertarian* eschews utilitarianism as a basis for government policy. The decision whether to own and carry a weapon for self-defense belongs to the individual, who (by his decision) accepts responsibility for his actions**. The role of the state in the matter is to deter aggressive acts on the part of criminals and psychopaths by visiting swift and certain justice upon them when they commit such acts.

CONCLUSION

Utilitarianism compromises liberty because it accords no value to the abilities, knowledge, and preferences of individuals. Decisions, to a utilitarian, are valid only if they serve to increase collective happiness, which is a mere fiction. Utilitarianism is nothing more than an excuse for imposing the utilitarian’s prejudices about the way the world ought to be.

* Libertarianism, by my reckoning, spans anarchism and the two major strains of minarchism: left-minarchism and right-minarchism. The internet-dominant strains of libertarianism (anarchism and left-minarchism) are, in fact, antithetical to liberty because they denigrate civil society. (For more on the fatuousness of the dominant strains of “libertarianism,” see “On Liberty” and “The Meaning of Liberty”.) The conservative traditionalist (right-minarchist) is both a true libertarian and a true conservative.

** Criminals and psychopaths accept responsibility de facto, as persons subject to the laws that forbid the acts that they perform. Sane, law-abiding adults accept responsibility knowingly and willinglly. Restricting the ownership of firearms necessarily puts sane, law-abiding adults at the mercy of criminals and psychopaths.